( ) IT’S COMING: Knowing that a Ukrainian offensive will soon target Melitopol, Chechen mercenaries offered 80,000 ₽ (~$1,300 ) for anyone who'd help dig trenches. When no one would take their money, they resorted to threats to make villagers to work: https://twitter.com/ChuckPfarrer/status/1592345653195472898/photo/1

( ) KHERSON CITY/14 NOV/ On 12-13 NOV, 4 explosions in the city were attributed to RU mines & long-fused explosives. In separate incidents, two anti-vehicle mines wounded 6 rail workers, & an automobile struck a RU road mine injuring six family members. RU sorties UAVs over the area: https://twitter.com/ChuckPfarrer/status/1592154092545413122/photo/1

ASSESSMENT

RUSSIAN OFFENSIVE CAMPAIGN , NOVEMBER 14, 2022

Kateryna Stepanenko, Karolina Hird, Layne Philipson, Angela Howard, Yekaterina Klepanchuk, Madison Williams, and Frederick W. Kagan

November 14, 8:30pm ET

Click here to see ISW’s interactive map of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This map is updated daily alongside the static maps present in this report.

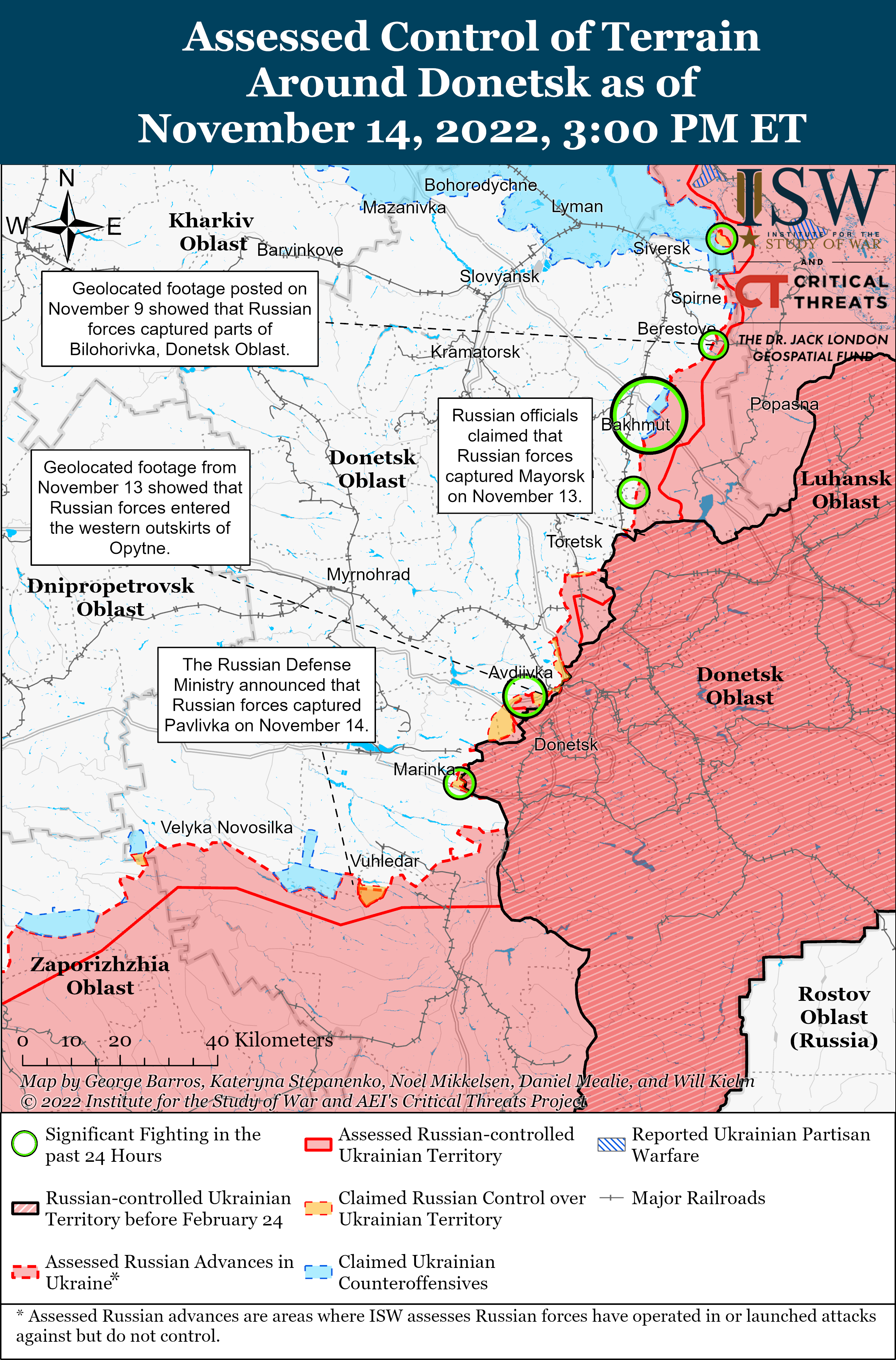

The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) escalated claims of Russian territorial gains in Donetsk Oblast on November 13 and 14, likely to emphasize that Russian forces are intensifying operations in Donetsk Oblast following withdrawal from the right bank of Kherson Oblast. The Russian MoD claimed that Russian forces completed the capture of Mayorsk (20km south of Bakhmut) on November 13 and of Pavlivka (45km southwest of Donetsk City) on November 14 after several weeks of not making claims of Russian territorial gains.[1] As ISW assessed on November 13, Russian forces will likely recommit troops to Donetsk Oblast after leaving the right bank of Kherson Oblast, which will likely lead to an intensification of operations around Bakhmut, Donetsk City, and in western Donetsk Oblast.[2] Russian forces will likely make gains in these areas in the coming days and weeks, but these gains are unlikely to be operationally significant. The Russian MoD is likely making more concrete territorial claims in order to set information conditions to frame Russian successes in Donetsk Oblast and detract from discontent regarding losses in Kherson Oblast.

Russian mil bloggers seized on Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s November 14 visit to Kherson City to criticize Russian military capacity more substantively than in previous days during the Russian withdrawal from the right bank of Kherson Oblast. Russian milbloggers largely complained that Zelensky arrived in Kherson City and was able to move around with relatively little concern about Russian strikes in his vicinity and questioned why Russian forces did not launch strikes on Zelensky.[3] One prominent milblogger noted that this shows that Russia does not want to win the war and criticized Russian forces for allowing Zelensky to step foot on “Russian territory.”[4] Russian milbloggers have notably maintained a relatively muted response to the Russian loss of the right bank in the past days, as ISW has previously reported.[5] The clear shift in rhetoric from relatively exculpatory language generally backing the withdrawal as a militarily sound decision to ire directed at Russian military failures suggests that Russian military leadership will likely be pressured to secure more direct gains in Donetsk Oblast and other areas.

Wagner Group financier Yevgeniy Prigozhin continues to establish himself as a highly independent, Stalinist warlord in Russia, becoming a prominent figure within the nationalist pro-war community. Prigozhin commented on a Russian execution video of a reportedly exchanged Wagner prisoner of war, Yevgeniy Nuzhin, sarcastically supporting Nuzhin’s execution and denouncing him as a traitor to the Russian people.[6] Most sources noted that Wagner executed Nuzhin following a prisoner exchange on November 10, but a few claimed that Wagner kidnapped the serviceman via Prigozhin’s connections to the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) and the Russian General Staff.[7] Prigozhin claimed that Nuzhin planned his escape to free Ukraine and used the opportunity to compare Nuzhin to Russian elites who disregard the interests of the Russian people and fly away from Russia‘s problems in their personal business jets.[8] The Russian nationalist community overwhelmingly welcomed the public punishment of the supposed deserter, noting that the Wagner command is undertaking appropriate military measures to discipline its forces.[9] Some milbloggers even compared the execution to Joseph Stalin’s “heroic” execution of Russian Marxist revolutionary Leon Trotsky who had also fled Bolshevik Russia, further confirming Prigozhin’s appeal among the proponents of Stalin’s repressive legacy.[10] Prigozhin is taking actions that will resonate with a constituency interested in the ideology of Russia’s national superiority, Soviet brutalist strength, and distastefulness of the Kremlin’s corruption, which Russian President Vladimir Putin has used as a political force throughout his reign.

Prigozhin is steadily using his participation in the Russian invasion of Ukraine to consolidate his influence in Russia. One mil blogger voiced a concern that the integration of Wagner mercenaries into Russian society is “the destruction of even the illusion of legality and respect for rights in Putin’s Russian Federation.”[11] The mil blogger added that Prigozhin is seizing the initiative to expand Wagner’s power in St. Petersburg while Russian security forces are “asleep.” Such opinions are not widespread among Russian nationalists but highlight some concerns with Prigozhin’s rapid expansion amid the Russian “special military operation” and its implications on the Putin regime. Prigozhin, for example, has requested that the FSB General Prosecutor’s office investigate St. Petersburg Governor Alexander Beglov for high treason after St. Petersburg officials denied a construction permit for his Wagner Center in the city.[12] He had also publicly scoffed at the Russian bureaucracy when asked if his forces will train at Russian training grounds, likely to further assert the independence of his forces.[13] Prigozhin’s unhinged antics in the political sphere are unprecedented in Putin’s regime.

Key Takeaways

- The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) escalated claims of Russian territorial gains in Donetsk Oblast on November 13 and 14, likely to emphasize that Russian forces are intensifying operations in Donetsk Oblast following their withdrawal from the right bank of Kherson Oblast.

- Russian mil bloggers seized on Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s November 14 visit to Kherson City to criticize Russian military capacity more substantively than in previous days during the Russian withdrawal from the right bank of Kherson Oblast.

- Wagner Group financier Yevgeniy Prigozhin continues to establish himself as a highly independent, Stalinist warlord in Russia, becoming an even more prominent figure within the nationalist pro-war community.

- Ukrainian forces continued counteroffensive operations on the Svatove-Kreminna line and clashed with Russian troops near Bilohorivka.

- Russian forces unsuccessfully attempted to regain positions in northeastern Kharkiv Oblast.

- Russian forces intensified offensive operations in Donetsk Oblast and claimed to have gained territory around Bakhmut and southwest of Donetsk City.

- Russian sources claimed that Ukrainian troops launched an unsuccessful raionto the Kinburn Spit.

- Russian President Vladimir Putin signed additional decrees refining mobilization protocols and expanding military recruitment provisions, likely in an ongoing effort to reinforce Russian war efforts.

- Russian occupation officials continued to drive the “evacuation” and forced relocation of residents in occupied territories and took efforts to move occupation elements farther from the Dnipro River.

We do not report in detail on Russian war crimes because those activities are well-covered in Western media and do not directly affect the military operations we are assessing and forecasting. We will continue to evaluate and report on the effects of these criminal activities on the Ukrainian military and population and specifically on combat in Ukrainian urban areas. We utterly condemn these Russian violations of the laws of armed conflict, Geneva Conventions, and humanity even though we do not describe them in these reports.

- Ukrainian Counteroffensives—Eastern Ukraine

- Russian Main Effort—Eastern Ukraine (comprised of one subordinate and two supporting efforts)

- Russian Subordinate Main Effort—Capture the entirety of Donetsk Oblast

- Russian Supporting Effort—Southern Axis

- Russian Mobilization and Force Generation Efforts

- Activities in Russian-occupied Areas

Ukrainian Counteroffensives (Ukrainian efforts to liberate Russian-occupied territories)

Eastern Ukraine: (Eastern Kharkiv Oblast-Western Luhansk Oblast)

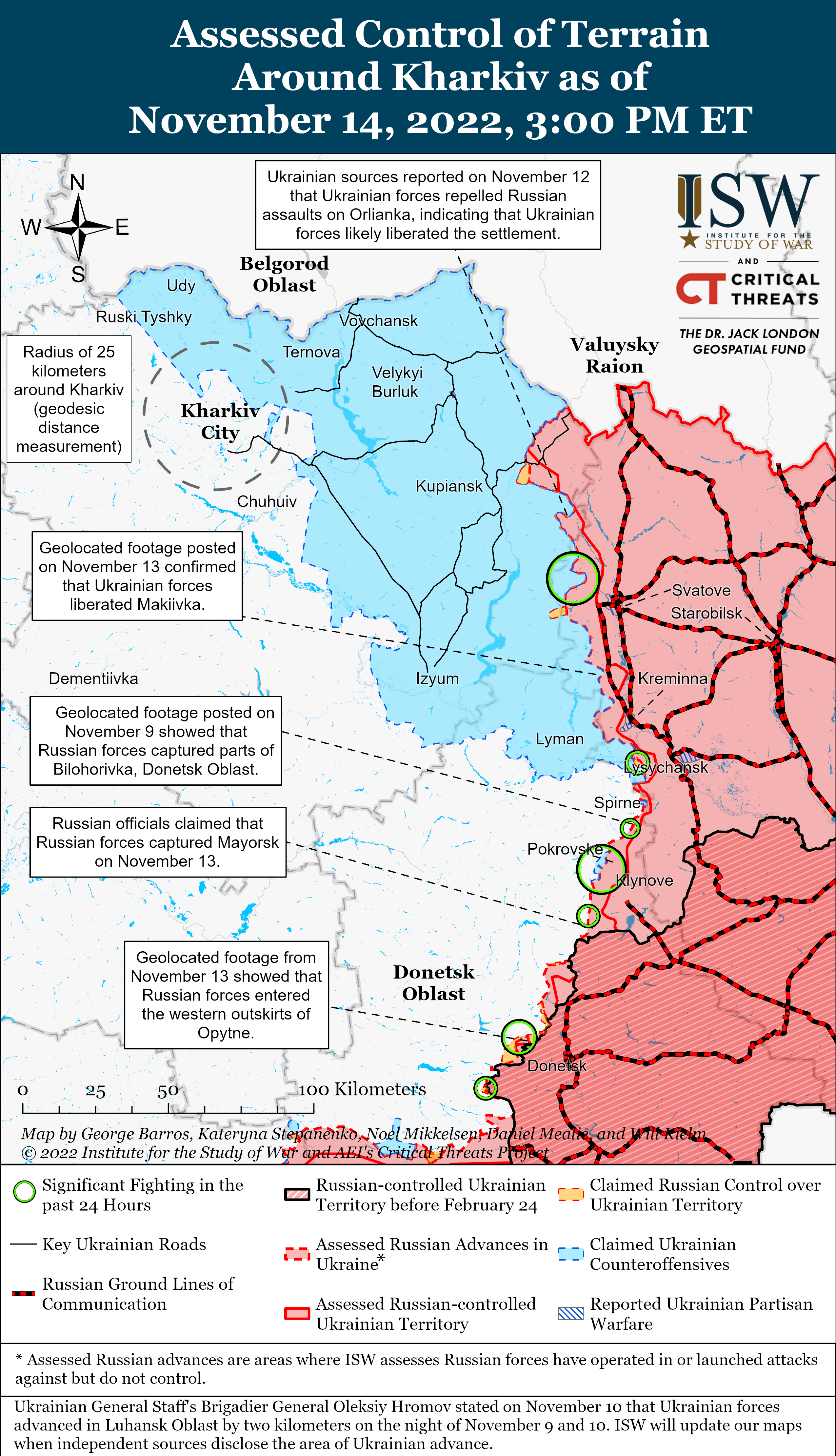

Ukrainian forces continued their counteroffensive operations on the Svatove-Kreminna line on November 13 and 14. Geolocated footage published on November 13 confirmed that Ukrainian forces liberated Makiivka, approximately 23km southwest of Svatove.[14] Commander of the Russian combat army reserve unit BARS-13, Sergey Femchenkov, claimed that the situation on the Svatove frontline “escalated,” forcing Russian forces to retreat from the Makiivka area.[15] Ukrainian and Russian sources reported ongoing clashes in the direction of Novoselivske, Volodymyrivka, and Stelmakhivka (all just northwest of Svatove) in the direction of the R66 highway.[16] Some Russian milbloggers noted that motorized rifle elements of the 1st Tank Army are holding defensive positions in the vicinity of Novoselivske.[17] The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) also claimed that Ukrainian forces continued to attack Russian positions in the Chervonopopivka area, fewer than 10km northwest of Kreminna.[18] The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Ukrainian forces stopped Russian assaults near Torske, about 16km due west of Kreminna.[19] Ukrainian forces also continued to target Russian logistics on the Svatove-Kreminna line, and geolocated footage showed the aftermath of a Ukrainian HIMARS strike on a Russian base on Miluvatka, just south of Svatove.[20]

Ukrainian and Russian forces engaged in clashes northwest of Lysychansk. The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Ukrainian forces repelled Russian attacks on Bilohorivka, Luhansk Oblast, approximately 13km northwest of Lysychansk.[21] Russian sources for the second time since November 7 claimed that Wagner Group troops and the Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR) units broke Ukrainian defenses in Bilohorivka and entered the settlement.[22]

Russian forces unsuccessfully attempted to regain positions in northeastern Kharkiv Oblast on November 13. Ukrainian and Russian sources claimed that a Russian attack helicopter conducted a sortie against Ukrainian positions in Terranova (about 31km northeast of Kharkiv City), and a Russian mil blogger noted that Russian forces failed to get a foothold in the settlement on November 13.[23] Russian forces also launched missile strikes from S-300 air defense systems on an enterprise in Kharkiv City on November 14.[24]

Russian Main Effort—Eastern Ukraine

Russian Subordinate Main Effort—Donetsk Oblast (Russian objective: Capture the entirety of Donetsk Oblast, the claimed territory of Russia’s proxies in Donbas)

Russian forces intensified offensive operations around Bakhmut on November 13 and 14. The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Ukrainian forces repelled Russian ground attacks near Bakhmut, Bilohorivka (about 20km northeast of Bakhmut), Spirne (30km northeast of Bakhmut), Toretsk (25km southwest of Bakhmut), and Kurdyumivka (13km southwest of Bakhmut).[25] The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) and Russian sources claimed that Russian forces seized Mayorsk (20km south of Bakhmut) on November 13, but Ukrainian Armed Forces spokesperson Serhiy Cherevatyi disputed these claims.[26] ISW is unable to independently confirm these reports. Russian sources claimed that Russian forces also conducted ground assaults northeast of Bakhmut near Verkhnokamianske, Spirne, and Bilohorivka.[27] Russian sources also claimed that Wagner forces advanced deep into the southeastern outskirts of Bakhmut, and that fierce fighting between Ukrainian and Wagner forces persists in the southeastern outskirts of Soledar (about 12km northeast of Bakhmut).[28] These sources claimed that Ukrainian forces are equipping their strongholds in the path of Russian forces, near Bakhmut and Soledar.[29] The Ukrainian government reported that Russian forces dropped prohibited chemical weapons, several K-51 aerosol grenades, on Ukrainian strongholds on November 14.[30] The use of chemical weapons such as K-51 aerosol grenades is explicitly prohibited by the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).[31] Both Russian and Ukrainian forces intensified shelling, missile, and artillery strikes along the contact line in the Bakhmut area.[32]

Russian forces intensified offensive operations around Avdiivka–Donetsk City on November 13 and 14. The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Ukrainian forces repelled Russian ground attacks near Krasnohorivka, Pervomaiske, and Vodiane, on the northwestern outskirts of Donetsk City, and Marinka and Novomykhailivka on the southwestern outskirts of Donetsk City.[33] A Russian source claimed that Russian forces slowly advanced through Ukrainian fortified areas near Marinka, Krasnohorivka, and Novomykhailivka.[34] Russian sources claimed that Russian forces slowly advanced through Ukrainian fortified areas near Pervomaiske, Vodiane, and Nevelske (19km northwest of Donetsk City).[35] Geolocated footage posted on November 12 showed that Russian forces advanced into the northwestern outskirts of Opytne (about 12km northwest of Donetsk City), and Russian sources claimed that Russian troops are attempting to push Ukrainian forces farther west of the settlement.[36] A Russian source reported that Ukrainian forces set up mine barriers in the Russian forces’ path to slow this Russian push west.[37] One Russian mil blogger claimed that Russian forces aim to capture Vodiane, which would allow them to bypass Avdiivka and ultimately take Tonenke (about 19km northwest of Donetsk City), in an effort to cut off Ukrainian supply lines in the Avdiivka-Donetsk City area.[38] Both Russian and Ukrainian forces intensified shelling, missile, and artillery strikes along the contact line in the Avdiivka–Donetsk City area.[39]

Russian forces claimed to have made gains southwest of Donetsk City on November 13 and 14. The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) and Russian news outlets claimed that Russian troops captured Pavlivka (45km southwest of Donetsk City) on November 14 after Ukrainian forces conducted unsuccessful counterattacks near Pavlivka and Nikolske on November 13.[40] The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Ukrainian forces repelled a Russian assault near Pavlivka on November 13, while Russian sources claimed that Russian forces continued to consolidate control over the northern outskirts of Pavlivka.[41] A Russian milblogger claimed that Russian forces conducted assault operations from the direction of Pavlivka in an attempt to dislodge Ukrainian forces from behind the Kashlahach River.[42]Russian sources claimed that advancing units of the Russian 155th Naval Infantry Brigade of the Pacific Fleet, the 40th Naval Infantry Brigade, and the “Kaskad” Battalion killed a large number of Ukrainian personnel who did not have time to withdraw from positions in Pavlivka on November 13 and took the remaining Ukrainian servicemembers in Pavlivka as prisoners of war on November 14.[43] Certain Russian sources claimed that Russian forces made no significant progress south of Novomykhailivka due to Ukrainian forces using elevation differences between Pavlivka and Vuhledar to their advantage.[44] The Ukrainian General Staff reported that Russian forces continued routine shelling along the line of contact in Donetsk Oblast and eastern Zaporizhia Oblast on November 13 and 14.[45]

Supporting Effort—Southern Axis (Russian objective: Maintain frontline positions and secure rear areas against Ukrainian strikes)

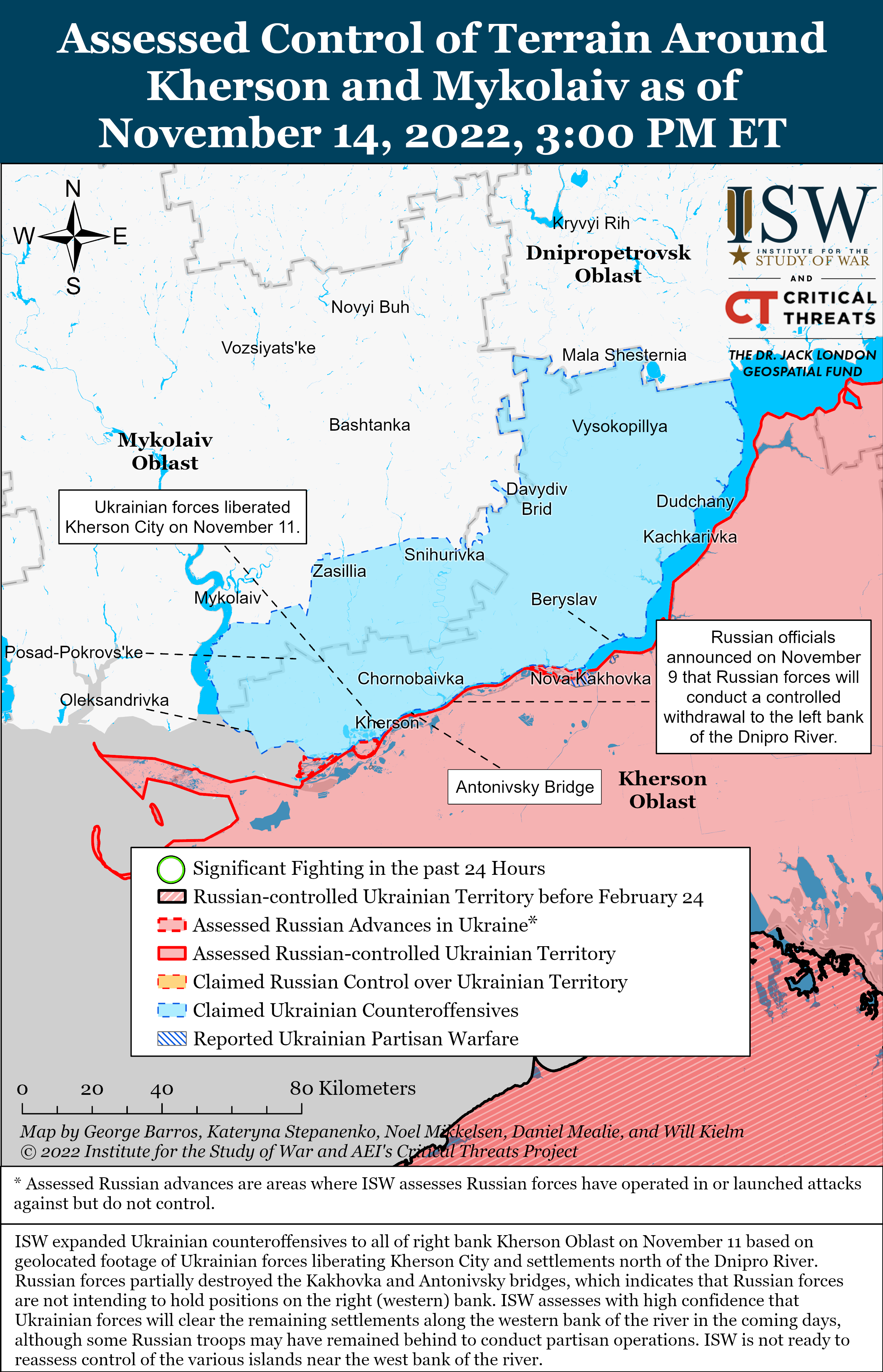

Note: ISW will report on activities in Kherson Oblast as part of the Southern Axis in this and subsequent updates. Ukraine’s counteroffensive in right-bank Kherson Oblast has accomplished its stated objectives, so ISW will not present a Southern Ukraine counteroffensive section until Ukrainian forces resume counteroffensives in southern Ukraine.

Russian forces continued defensive actions on the left bank of Kherson Oblast on November 13 and 14. Geolocated satellite imagery posted on November 13 shows newly created Russian defensive lines along the left bank of the Dnipro, east of Beryslav around Hornostaivka (28km northeast of Beryslav), Liubymivka (8km southeast of Beryslav), and Petropavlivka (25km southeast of Beryslav).[46] Additional satellite imagery shows the development of Russian defensive lines in Lukyanivka (16km southeast of Beryslav) between October 8 and November 10.[47] Ukrainian military sources reported that Russian troops are conducting defensive preparations on the left bank and striking Ukrainian positions and residential communities on the right bank.[48] The spokesperson for Ukraine’s Southern Forces, Nataliya Humenyuk, stated that Russian forces struck an abandoned equipment concentration in Chornobaivka (just northwest of Kherson City) on November 13, which the Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) claimed was a strike on a Ukrainian command post.[49] Ukrainian sources also stated that Russian forces conducted a mortar strike on November 14 on the private sector of Hornostaivka, a settlement on the left bank of the Dnipro River, because civilians refused to evacuate.[50]

Russian sources widely claimed that Ukrainian troops launched a limited raid and attempted to land on the Kinburn Spit on the night of November 13 and 14. Russian mil bloggers reported that Ukrainian landing groups formed in Ochakiv, Mykolaiv Oblast, and attempted to land on the Kinburn Spit at Pokrovske, but that Russian forces destroyed the grouping during the ensuing battle.[51] Ukrainian sources did not comment on these claims. Russian mil bloggers voiced concerns that this raid is indicative of Ukraine’s ability to land on the left bank of the Dnipro River.[52]

Russian forces continued routine artillery, air, and missile strikes in Zaporizhia, Mykolaiv, and Dnipropetrovsk oblasts and on the right bank of Kherson Oblast on November 13 and 14.[53] Ukrainian sources reported that Russian forces launched anti-aircraft missiles at Ochakiv, Mykolaiv Oblast on November 14, which Russian sources reported was intended to disrupt Ukrainian fire control over the Kinburn Spit.[54] Ukrainian forces notably struck Russian concentration areas on the left bank of Kherson Oblast on November 13 and 14 and targeted personnel concentrations in Dnipryany, Chaplynka, and Hola Prystan.[55]

Mobilization and Force Generation Efforts (Russian objective: Expand combat power without conducting general mobilization)

Russian President Vladimir Putin signed additional decrees refining mobilization protocols and expanding military recruitment provisions, likely in an ongoing effort to reinforce Russian war efforts. Putin decreed that foreign citizens can serve in the Russian armed forces on November 14.[56] The decree also allows Russian officials to conscript Russian dual-nationals or foreigners with residence permits.[57] Such provisions will allow the Kremlin to recruit forces internationally and among immigrant populations in Russia. Recruitment of foreigners can also ignite further ethnoreligious conflicts that have been plaguing Russian ad hoc forces, however.

Putin is establishing enforcement measures for censorship of foreigners with acquired Russian citizenship, which would allow military recruitment officials to further carry out covert mobilization and respond to criticism of the failures of the Russian military campaign in Ukraine. Putin proposed an amendment that would deprive people of their acquired Russian citizenship if they spread “fakes about the Russian Armed Forces” or affiliate with “extremist organizations” that advocate against Russian territorial integrity. The Russian State Duma is also considering a law that would deprive residents of acquired Russian citizenship if they surrender or evade military service.[58] Both proposals excluded Russian-born citizens and are likely attempts to silence immigrant groups and ethnically based civil society in Russia. The amendment would task the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) with prosecuting individuals with such views, and Putin may be attempting to set up an internal repression apparatus. ISW previously assessed that Putin has never built an internal repression apparatus like the Soviets, instead relying on control over the information space.[59]

Putin may also be refining conditions for future force-generation efforts, such as a new wave of mobilization. Putin decreed that individuals with drug possession and consumption criminal charges will not be able to sign a contract with the Russian Armed Forces, likely in an effort to appear to address instances of substance abuse among new recruits and mobilized men.[60] It is unclear if Russian officials will actually follow Putin’s order prohibiting individuals with drug-related charges from serving, but the Wagner Group private military company (PMC) will likely continue to recruit these individuals regardless of Putin’s order regarding the conventional Russian military.

Russian authorities continue their struggle to integrate combat forces lacking a coordinated central command structure. Putin eliminated one inconsistency in Russian and Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics’ (DNR and LNR) force-generation policy by decreeing the demobilization of students in occupied Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts on November 13.[61] The students were mobilized as part of DNR/LNR efforts rather than as part of the general Russian mobilization effort. The DNR and LNR will likely maintain their covert mobilization practices to ensure a supply of reinforcements, however. The Ukraine Resistance Center stated on November 14 that Russian forces continued to forcibly mobilize students in Donetsk and Luhansk from universities.[62] It is unclear whether DNR and LNR officials had any input into Putin’s decision, though DNR Head Denis Pushilin thanked Putin for giving DNR students the same opportunity as students in “other regions of Russia.”[63] A prominent Russian mil blogger also noted that such issues will not resolve instantly due to divergences between DNR, LNR, and Russian laws.[64] Another Russian milblogger noted that Russian hospitals continue to deny treatment to DNR and LNR servicemen, and it is likely that Russian Armed Forces’ disparaging attitude towards non-Russian forces will persist throughout Russian efforts to consolidate the proxy republics’ and Russian Federation’s legalthe systems.[65] The resolution of discrepancies between Russia and the forces the Kremlin is working to absorb has contributed to friction between the force groups, as ISW has previously reported.[66]

The aftermath of partial mobilization is continuing to have domestic social ramifications in Russia. Social media footage from November 13 shows a large group of mobilized servicemembers in Patriot Park, Moscow Oblast, protesting against the poor quality of their training and threatening their commander for disregarding training and material necessities.[67] The protestors angrily questioned why mobilized recruits are conducting small-arms fire exercises at tank training grounds.[68] The families of forcibly mobilized servicemembers similarly continue to claim that the Russian command deployed their loved ones to the frontlines in Ukraine without training or equipment and stated that they have lost contact with their relatives.[69] The Sverdlovsk and Voronezh military registration authorities are reportedly refusing to issue the badge numbers of certainly mobilized servicemen, which makes it impossible for families to view information about service payments belonging to their deceased loved ones on the battlefield.[70]

Activity in Russian-occupied Areas (Russian objective: consolidate administrative control of occupied and annexed areas; forcibly integrate Ukrainian civilians into Russian sociocultural, economic, military, and governance systems)

Russian occupation officials continued to drive the “evacuation” and forced relocation of residents in occupied territories on November 14. The Ukrainian General Staff reported on November 14 that Russian officials are evicting Ukrainian citizens from their homes in some temporarily occupied settlements in Zaporizhia Oblast to house Russian servicemen.[71] The Ukrainian General Staff also reported on November 14 that Russian forces plan to completely evacuate the civilian population from Rubizhne, Kreminna, and Severodonetsk, all of which are in Russian-occupied Luhansk Oblast.[72]

Russian occupation officials continued efforts to relocate their administrative presence away from the Dnipro River in Kherson Oblast on November 14. The Ukrainian Resistance Center reported on November 14 that the Russian Duma Liberal Democratic deputies Leonid Slutsky, Vladimir Koshelev, and Vladimir Sibyagin are supervising Kherson occupation officials as they attempt to launch operations of the administrative center after officially moving the Kherson Oblast temporary administrative capital to Henichesk on November 12.[73] The Ukrainian Resistance Center also reported that Russian occupiers are evacuating the families of Russian workers from Zaliznyi Port, Kherson Oblast.[74]

Russian authorities are continuing to import Russian citizens to serve in occupation administrations, replacing possibly ineffective Ukrainian collaborators and personnel from Zaporizhia, Kherson, and Luhansk Oblasts. The Ukrainian Resistance Center reported on November 13 that Russian occupation officials have appointed new heads of prosecutors’ offices in occupied territories after chief prosecutors arrived in Zaporizhia, Kherson, and Luhansk Oblasts on November 7.[75] A Russian source similarly claimed on November 14 that Russia is abolishing the LNR’s prosecution office to further integrate the territory into Russia.[76]

Russian occupation officials are continuing efforts to erode Ukrainian national identity among residents of occupied territories. Enerhodar Mayor Dmytro Orlov stated on November 14 that Russian occupation officials in Enerhodar, Zaporizhia Oblast, destroyed Ukrainian history textbooks and literature.[77] The Ukrainian Resistance Center reported on November 14 that the Commissioner for Children’s Rights under the Russian Presidential Administration, Maria Lvova-Belova, is personally responsible for the forced deportation and adoption of Ukrainian children into Russian families for the purpose of forcing assimilation into Russia.[78]

Note: ISW does not receive any classified material from any source, uses only publicly available information, and draws extensively on Russian, Ukrainian, and Western reporting and social media as well as commercially available satellite imagery and other geospatial data as the basis for these reports. References to all sources used are provided in the endnotes of each update.

References

[1] https://t.me/mod_russia/21716; https://t.me/mod_russia/21739

[2] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-ass...

[3] https://t.me/vladlentatarsky/17433; https://t.me/rybar/41143

[4] https://t.me/rybar/41143; https://t.me/NeoficialniyBeZsonoV/19817

[5] https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-ass...

[6] https://t.me/concordgroup_official/27

[7] https://t.me/m0sc0wcalling/14399; https://t.me/NetGulagu/3788; https:/... https://t.me/NetGulagu/3789

[8] https://t.me/concordgroup_official/27

[9] https://vk dot com/concordgroup_official?w=wall-177427428_1435; https://t.me/rybar/41109; https://t.me/niviynii/769; https://t.me/nivi...

[10] https://t.me/vysokygovorit/9967

[11] https://t.me/m0sc0wcalling/14397

[12] https://t.me/concordgroup_official/25; https://understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-ass...

[13] https://t.me/concordgroup_official/26

[14] https://twitter.com/GirkinGirkin/status/159173918170090291; https://twi...

[15] https://t.me/wargonzo/9257

[17] https://t.me/razved_dozor/2839 ; https://t.me/boris_rozhin/70230

[18] https://t.me/mod_russia/21736; https://t.me/mod_russia/21716

[19] https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid02YCSX87CsqK2udvjM2z...

[20] tps://twitter.com/auditor_ya/status/1591788457864892421; https://twitter.com/666_mancer/status/1591354083252015104; https://t.me... https://t.me/voenkorKotenok/42651

[21] https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid02DK4f2arU8MDofYKaa2...

[22] https://t.me/rybar/41112; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder...

[23] https://t.me/rybar/41120; https://www.facebook.com/easternforces/posts/...

[24] https://t.me/stranaua/75066l https://t.me/ihor_terekhov/547; https://t...

[25] https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid02DK4f2arU8MDofYKaa2...

[26] https://t.me/mod_russia/21716; https://t.me/pushilindenis/2894; https:...

[27] https://t.me/wargonzo/9231; https://t.me/wargonzo/9250; https://t.me/rybar/41106

[28] https://t.me/rybar/41112; https://t.me/wargonzo/9250; https://t.me/ryb...

[29] https://t.me/russkiy_opolchenec/34952; https://t.me/rybar/41112

[30] https://www.facebook.com/DPSUkraine/posts/pfbid0Qo2aqg8JknMVSU8DgxxsDrfc...

[31] https://zakon.rada.gov(dot)ua/laws/show/995_182#Text; https://www.opcw.org/chemical-weapons-convention

[32] https://t.me/millnr/9721; https://t.me/rybar/41112; https://twitter.co...

[33] https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid02DK4f2arU8MDofYKaa2...

[34] https://t.me/wargonzo/9231; https://t.me/wargonzo/9250; https://t.me/r...

[35] https://t.me/rybar/41106; https://t.me/NeoficialniyBeZsonoV/19821;

[36] https://twitter.com/666_mancer/status/1591520349354876928; https://t.me... https://twitter.com/Militarylandnet/status/1591521686163435522 ; https://twitter.com/GeoConfirmed/status/1591589815019253760; https://t....

[37] https://t.me/rybar/41133; https://t.me/rybar/41106;

[38] https://t.me/boris_rozhin/70106

[39] https://t.me/nm_dnr/9402; https://t.me/TRO_DPR/9665; https://t.me/TRO_...

[40] https://t.me/mod_russia/21716 ; https://t.me/mod_russia/21739 ; http...

[41] https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid02YCSX87CsqK2udvjM2z...

[42] https://t.me/wargonzo/9231

[43] https://t.me/Bratchuk_Sergey/22576 ; https://t.me/boris_rozhin/70169 ...

[44] https://t.me/boris_rozhin/70259; https://t.me/SergeyKolyasnikov/44187

[45] https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid08gdEhBLPwrrJVfPJF9C...

[46] https://twitter.com/auditor_ya/status/1591788447379128320; https://twit...

[47] https://twitter.com/neonhandrail/status/1591590694606753793

[48] https://www.facebook.com/okPivden/videos/1930029017201206/; https://www... ua/2022/11/14/rechnyczya-syl-oborony-pivdnya-rozpovila-pro-obstrily-zvilnenyh-naselenyh-punktiv/

[49] https://armyinform.com dot ua/2022/11/14/bojova-robota-na-pivdni-ukrayiny-ne-zupynylasya-nataliya-gumenyuk/; https://t.me/mod_russia/21736

[50] https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid02DK4f2arU8MDofYKaa2...

[51] https://t.me/epoddubny/13643; https://t.me/russkiy_opolchenec/34953; h...

[52] https://t.me/syriantube/11818

[53] https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid08gdEhBLPwrrJVfPJF9C... ua/2022/11/14/rechnyczya-syl-oborony-pivdnya-rozpovila-pro-obstrily-zvilnenyh-naselenyh-punktiv/; https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1522365958245901; https://www.faceboo...

[54] https://t.me/mykolaivskaODA/3412; https://t.me/stranaua/75092; https:/...

[56] https://t.me/stranaua/75155; http://publication.pravo.gov.ru/Document/V...

[57] https://centralasia dot media/news:1818719

[58] https://t.me/stranaua/75125

[59] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[60] https://t.me/readovkanews/46815

[61] https://notes.citeam.org/mobilization-nov-12-13; https://t.me/meduzalive/73273 ; https://t.me/meduzalive/73274; https://t.me/TRO_DPR/9661; https://t.me/dnronline/85294; https://t.me/miroshnik_r/9554; https://t.me/NeoficialniyBeZsonoV/19804; https://t.me/RtrDonetsk/12011; https://t.me/epoddubny/13641

[62] https://sprotyv.mod dot gov.ua/2022/11/14/na-shodi-ukrayiny-rosiyany-mobilizuvaly-studentiv-psevdouniversytetiv/

[63] https://t.me/pushilindenis/2895

[64] https://t.me/boris_rozhin/70244

[65] https://twitter.com/GirkinGirkin/status/1591493817156644866/photo/1

[66] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[67] https://t.me/operativnoZSU/55779; https://notes.citeam.org/mobilization...

[68] https://t.me/operativnoZSU/55779; https://notes.citeam.org/mobilization...

[69] https://notes.citeam.org/mobilization-nov-12-13; https://t.me/ostorozhn...

[70] https://notes.citeam.org/mobilization-nov-12-13; https://t.me/horizonta...

[71] https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid02DK4f2arU8MDofYKaa2...

[72] https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid02d9Z7xA3UMqSykA8kuA...

[73] https://sprotyv dot mod.gov.ua/2022/11/13/rosiyany-namagayutsya-nalagodyty-robotu-okupaczijnoyi-administracziyi-v-genichesku/; https://ria dot ru/20221112/genichesk-1830990519.html; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... gov.ua/2022/11/14/rosiyany-vyvezly-svoyih-posipak-z-zaliznogo-portu-do-skadovska/

[74] https://sprotyv.mod dot gov.ua/2022/11/14/rosiyany-vyvezly-svoyih-posipak-z-zaliznogo-portu-do-skadovska/

[75] https://sprotyv dot mod.gov.ua/2022/11/13/okupanty-zavezly-svoyih-prokuroriv-na-tymchasovo-okupovani-terytoriyi/

[76] https://t.me/boris_rozhin/70251

[77] https://t.me/orlovdmytroEn/1259

[78] https://sprotyv.mod dot gov.ua/2022/11/14/upovnovazhena-putina-osobysto-kontrolyuye-vykradennya-ukrayinskyh-ditej-do-rf/