ASSESSMENT

RUSSIAN OFFENSIVE CAMPAIGN, DECEMBER 11,2022.

Riley Bailey, Kateryna Stepanenko, and Frederick W. Kagan

December 11, 9 pm ET

Click here to see ISW’s interactive map of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This map is updated daily alongside the static maps present in this report.

ISW is publishing an abbreviated campaign update today, December 11. This report discusses how the Belarusian regime’s support for the Russian invasion of Ukraine as well as Russian pressure on Belarus to become more involved further constrains Belarusian readiness and willingness to enter the war in Ukraine.

Russian officials consistently conduct information operations suggesting that Belarusian conventional ground forces might join Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Belarusian leaders including Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko sometimes play along with these information operations. The purpose of these efforts is to pin Ukrainian forces at the Belarusian border to prevent them from reinforcing Ukrainian operations elsewhere in the theater. Belarus is extraordinarily unlikely to invade Ukraine in the foreseeable future whatever the course of these information operations. A Belarusian intervention in Ukraine, moreover, would not be able to do more than draw Ukrainian ground forces away from other parts of the theater temporarily given the extremely limited effective combat power at Minsk’s disposal.

The Kremlin’s efforts to pressure Belarus to support the Russian offensive campaign in Ukraine are a part of a long-term effort to cement further control over Belarus. ISW previously assessed that the Kremlin intensified pressure on Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko to formalize Belarus’ integration into the Union State following the Belarusian 2020 and 2021 protests.[1] Russia particularly sought to establish a permanent military base in Belarus and direct control of the Belarusian military.[2] Russia has routinely tried to leverage its influence over Belarusian security and military affairs to place pressure on Belarus to support its invasion of Ukraine.[3] ISW assessed that Russian Minister of Defense Army General Sergei Shoigu meet with Lukashenko on December 3 to further strengthen bilateral security ties - likely in the context of the Russian-Belarusian Union State - and increase Russian pressure on Belarus to further support the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[4]

The Belarusian regime’s support for the Russian invasion has made Belarus a cobelligerent in the war in Ukraine. Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko offered Belarusian territory to Russian forces for the initial staging of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.[5] Belarusian territory offered critical ground lines of communication (GLOCs) to the Russian Armed Forces in their failed drive on Kyiv and their subsequent withdrawal from northern Ukraine.[6] ISW has previously assessed that Belarus materially supports Russian offensives in Ukraine and provides Russian forces with secure territory and airspace from which to attack Ukraine with high-precision weapons.[7]

Belarusian support for Russia’s war in Ukraine is likely degrading the Belarusian military’s material capacity to conduct conventional military operations of its own. The Belarusian open-source Hajun Project reported on November 14 that the Belarusian military transferred 122 T-72A tanks to Russian forces, likely under the guise of sending them for modernization work in the Russian Federation.[8]The Hajun Project reported on November 17 that Belarus transferred 211 pieces of military equipment to the Russian Armed Forces, including 98 T-72A tanks and 60 BMP-2s.[9] The confirmed transfer of 98 T-72 tanks represents roughly 18 percent of the Belarusian inventory of active main battle tanks, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies 2021 Military Balance report.[10] It is unclear if the 98 transferred tanks are part of the 122 tanks designated for modernization or if they are a separate collection of equipment. Neither is it clear that the tanks sent to Russia were part of the active Belarusian tank park or vehicles held in storage or reserve. Belarus lacks the capabilities to produce its own armored fighting vehicles making the transfer of this equipment to Russian forces both a current and a likely long-term constraint on Belarusian material capacities to commit mechanized forces to the fighting in Ukraine.[11]

Belarus is also likely drawing down its inventory of artillery munitions through munitions transfers to the Russian military. The Ukrainian Main Military Intelligence Directorate (GUR) reported on December 3 that Belarus has been transferring 122mm and 152mm artillery ammunition to the Russian Armed Forces throughout October and November.[12] The GUR reported on November 17 that Belarusian authorities are interested in establishing a closed cycle of production for these artillery shells and that Belarusian officials planned to meet with Iranian officials to discuss such closed production cycles of artillery munitions.[13] The GUR also reported on October 11 that a train with 492 tons of ammunition from the Belarusian 43rd Missile and Ammunition Storage Arsenal in Gomel arrived at the Kirovske Railway Station in Crimea on an unspecified date.[14]

Belarusian officials are likely trying to conceal the amount of military equipment they are sending to Russia to support its invasion of Ukraine. The Hajun Project reported on November 5 that the Belarusian State Security Committee, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the Belarusian Special Forces have instituted enhanced protection and surveillance of rail infrastructure and have banned trains carrying military equipment from passing through Belarusian cities.[15] Belarusian authorities likely are trying to prevent Western and Ukrainian intelligence agencies from fully assessing the extent of the Belarusian military equipment transfers to Russia. Belarus may be sending more extensive amounts of military equipment to Russian forces. Belarusian authorities may also be attempting to hide the extent of the transfers in order to mitigate the possible backlash against Lukashenko‘s degradation of the country’s military capacity and subservience to Moscow.

The Belarusian military is likely facing constraints on its capacity to train current and new personnel due to its supporting role in Russian force generation efforts. The Belarusian military is continuing to train Russian mobilized military personnel at the 230th Combined Arms Obuz-Lesnovsky Training Ground in Brest, Belarus and at other training facilities near Mozyr, Gomel, and Mogilev in Belarus as part of the Union States’ Regional Grouping of Forces (RGV).[16] The Belarusian Ministry of Defense reportedly drafted 10,000 conscripts into the Belarusian Armed forces as a part of its autumn conscription campaign, a similar number to those drafted in the autumn cycle in 2021.[17] The Belarusian training of these mobilized Russian servicemembers coincides with the start of the Belarusian military’s academic year.[18] The GUR reported on September 29 that Belarus was preparing to accommodate up to 20,000 mobilized Russian servicemembers.[19] The Ukrainian Resistance Center reported on November 25 that 12,000 Russian personnel were stationed in Belarus.[20] ISW previously assessed that Russian forces deployed the mobilized men for training in Belarus as part of the RGV due to Russia‘s degraded training capacity.[21]

The Belarusian military likely has a relatively limited capacity to train existing and new personnel. The Belarusian military has only six maneuver brigades and is comprised of roughly 45,000 active personnel split into two command headquarters.[22] The small Belarusian military likely has limited training capacity and infrastructure to support its own force generation efforts. Belarusian military officials are now responsible for training at least two times as many service members as the Belarusian military normally trains. Belarusian support for Russian force generation efforts would likely also constrain it from being able to train more Belarusian military personnel if Lukashenko wished to increase the number of drafted conscripts in the next conscription cycle to prepare for possible losses in combat following a putative Belarusian invasion of Ukraine.

The degradation of the Russian military through devastating losses in Ukraine would also hinder the deployment of Belarusian mechanized forces to fight alongside Russian troops. Belarusian forces should theoretically be able to operate in combined units with Russian mechanized forces. ISW previously assessed that Russia pursued efforts to integrate the Belarusian military into Russian-led structures in joint military exercises and permanent joint combined combat training centers before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.[23] The Belarusian military coordinated with the Russian military in the Zapad-2021 joint exercises in September of 2021 in which Russian and Belarusian units formed joint ”mobile tactical groups” that operated as single military units at the battalion level.[24] These combined units require a high degree of coordination and military training, and therefore Russian and Belarusian forces used elite units in such efforts. Russian units that took part in the joint exercises with Belarusian forces included elements of the 1st Guards Tank Army, the 76th Guards Air Assault Division, the 20th Combined Arms Army, the 31st Guards Air Assault Brigade, and the 106th Guards Airborne Division, all elite units that ISW has assessed have been severely degraded in Ukraine.[25] These Russian units now likely lack the capability to operate in combined formations with Belarusian forces and likely are unable to operate effectively in combined operations. Belarusian forces would likely have to operate together with poorly trained mobilized Russian personnel if they entered the war in Ukraine.[26] The outcome of efforts to form and use such combined units in combat is likely to be poor.

Lukashenko’s support for Russia’s war in Ukraine and Russian pressure on Belarus to join the fighting is likely causing friction within the Belarusian military. The Ukrainian General Staff reported on December 7 that soldiers of the Belarusian border service and the Belarusian Armed Forces are increasingly dissatisfied with the activities of the Belarusian military-political leadership due to the threat of Belarus entering the war in Ukraine.[27] Ukrainian sources reported on November 13 that social tensions between Belarusians and Russian forces in Brest Oblast intensified as Russian forces strained local hospitals due to unsanitary conditions at the 230th Combined Arms Obuz-Lesnovsky Training Ground.[28] The GUR reported on November 6 that internal memos from senior Belarusian military officers show numerous complaints from rank-and-file Belarusian servicemen about tensions with Russian mobilized personnel, particularly in relation to derogatory ethnic statements.[29]

Belarusian personnel is certainly aware of the significant losses that Russian forces suffered in Ukraine and likely do not wish to experience the same result. An October 25 CNN report detailed how the Belarusian military and hospitals treated many Russian casualties as the Russian military offensive to capture Kyiv failed.[30] Belarusian units that trained with elite Russian units that have since suffered heavy losses fighting in Ukraine are also likely aware of the extent of the casualties that the Russian army has faced in Ukraine. These Belarusian units likely know that their units and the Belarusian military as a whole would not fare better than Russian units which were far more capable and well-trained.

Elements within the Belarusian military have shown resistance to the idea of entering the war in Ukraine. A Belarusian lieutenant colonel posted a viral video on February 27 in which he called upon Belarusian military personnel to refuse orders if instructed to enter the war in Ukraine.[31] It is likely that some elements of the Belarusian Armed Forces would express reluctance or outright refusal if Lukashenko decided to invade Ukraine.

Lukashenko’s setting of information conditions likely further constrains Belarusian willingness to enter the war. Lukashenko continues to set informational conditions to resist Russian pressure to enter the war in Ukraine by claiming that NATO is preparing to attack Belarus.[32] Lukashenko would likely struggle to set information conditions justifying the Belarusian military’s involvement to the south in Ukraine that did not obviously contradict the supposed threat of NATO forces to the west that he has framed to the Belarusian public. Belarusian officials’ repeated invocations of the threat of NATO may have also instilled a misguided belief among some Belarusian government and military officials that a defensive posture in western Belarus is essential.

Belarus is already unlikely to invade Ukraine due to internal dynamics within the country. ISW has previously assessed that Lukashenko does not intend to enter the war in Ukraine due to the possibility of renewed domestic unrest if his security apparatus is weakened through participation in a costly war in Ukraine.[33] Lukashenko relied upon elements of the Belarusian Armed Forces in addition to Belarusian security services to quell popular protests against his rule in 2020 and 2021.[34] Committing a substantial amount of that security apparatus to the war in Ukraine would likely leave Lukashenko open to renewed unrest and resistance. Lukashenko is also likely aware that invading Ukraine would undermine his credibility as the leader of a sovereign country as it would be evident that Russia’s effort to secure full control of Belarus had succeeded.

Belarusian entry into the war would at worst force Ukraine to temporarily divert manpower and equipment from the current front lines. Ukrainian General Staff Deputy Chief Oleksiy Hromov stated on November 24 that 15,000 Belarusian military personnel, in addition to the 9,000 Russian personnel stationed in Belarus, could theoretically participate in the war with Ukraine.[35] Even if Lukashenko committed a substantially larger number of his forces to an offensive into Ukraine, the Belarusian military would still be a small force that would be unable to achieve any substantial operational success. ISW has previously assessed that a Russian or Belarusian offensive from Belarus would not be able to cut Ukrainian logistical lines to the West without projecting deeper into Ukraine than Russian forces did during the Battle of Kyiv when Russian forces were at their strongest.[36] A Belarusian invasion could not make such a drive, nor could it seriously threaten Kyiv. Belarus’ entry into the war would at worst divert Ukrainian forces away from the current front lines in eastern Ukraine.

Belarus will continue to help Russia fight its war in Ukraine even though Lukashenko is highly unlikely to send his army to join the fighting. Belarus can offer material to Russia that Russia cannot otherwise source due to international sanctions regimes against the Russian Federation that do not impact Belarus.[37] Belarusian provision of territory and airspace allows Russian forces to support their offensive operations in Ukraine and conduct their strikes on Ukrainian civilian targets from a safe haven.

Russian officials will continue to conduct information operations aimed at suggesting that Belarusian forces might invade Ukraine in order to pin Ukrainian forces at the Belarusian border. These information operations are extraordinarily unlikely to herald actual Belarusian intervention in the foreseeable future.

Key inflections in ongoing military operations on December 11:

- The Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) denied rumors on December 11 that General Valery Gerasimov resigned or was removed from his position as Chief of the General Staff.[38]

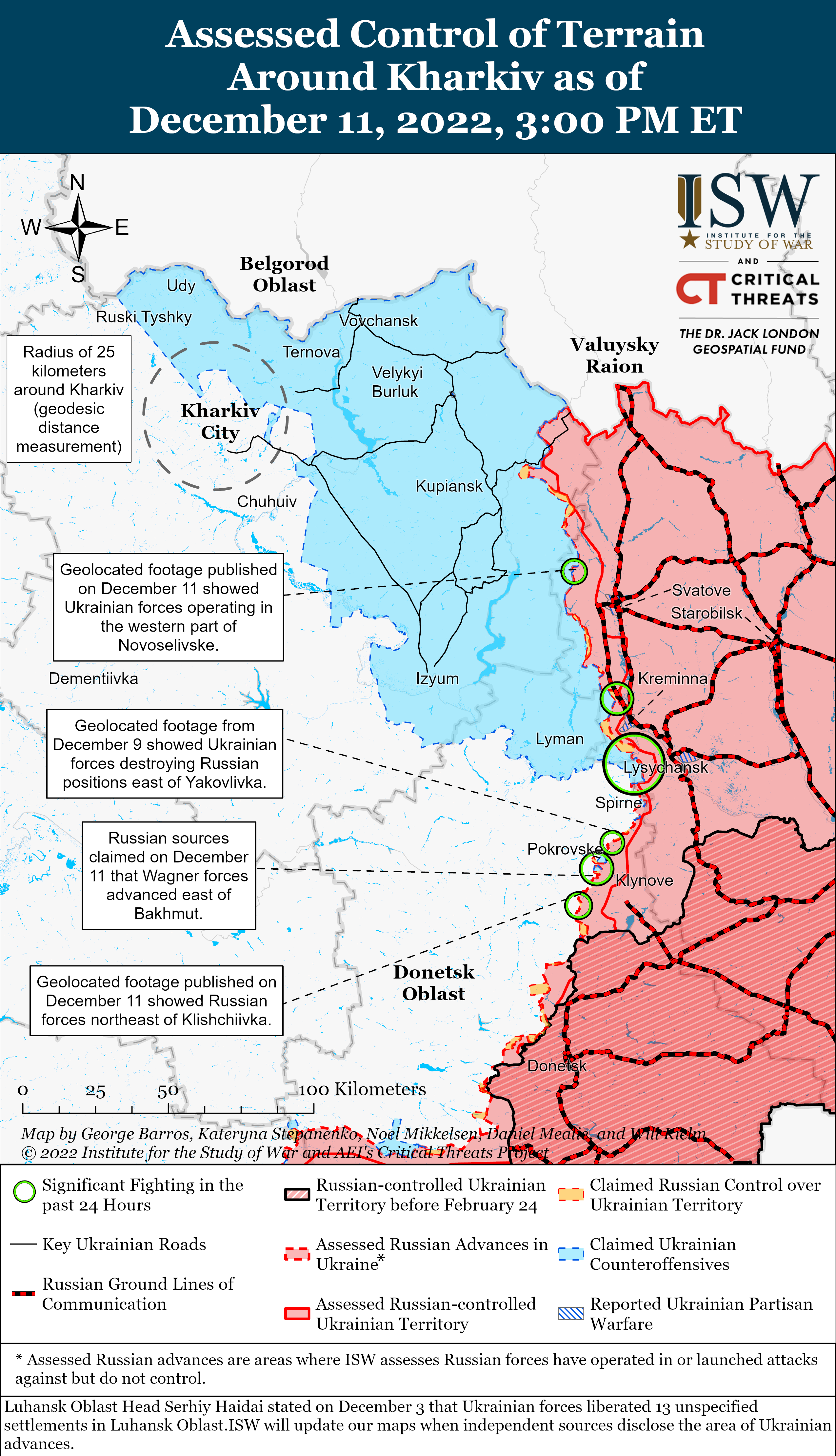

- Ukrainian and Russian sources reported that fighting continues along the Svatove-Kreminna line and near Lyman amidst poor weather conditions.[39]

- A Russiamil bloggerer claimed that Russian forces transferred over 200 pieces of equipment from the Kherson direction to the Kupyansk direction, and geolocated footage shows Russian T-90 tanks in Luhansk Oblast headed west.[40] A Ukrainian official stated that a larger Russian force grouping does not currently pose a threat.[41]

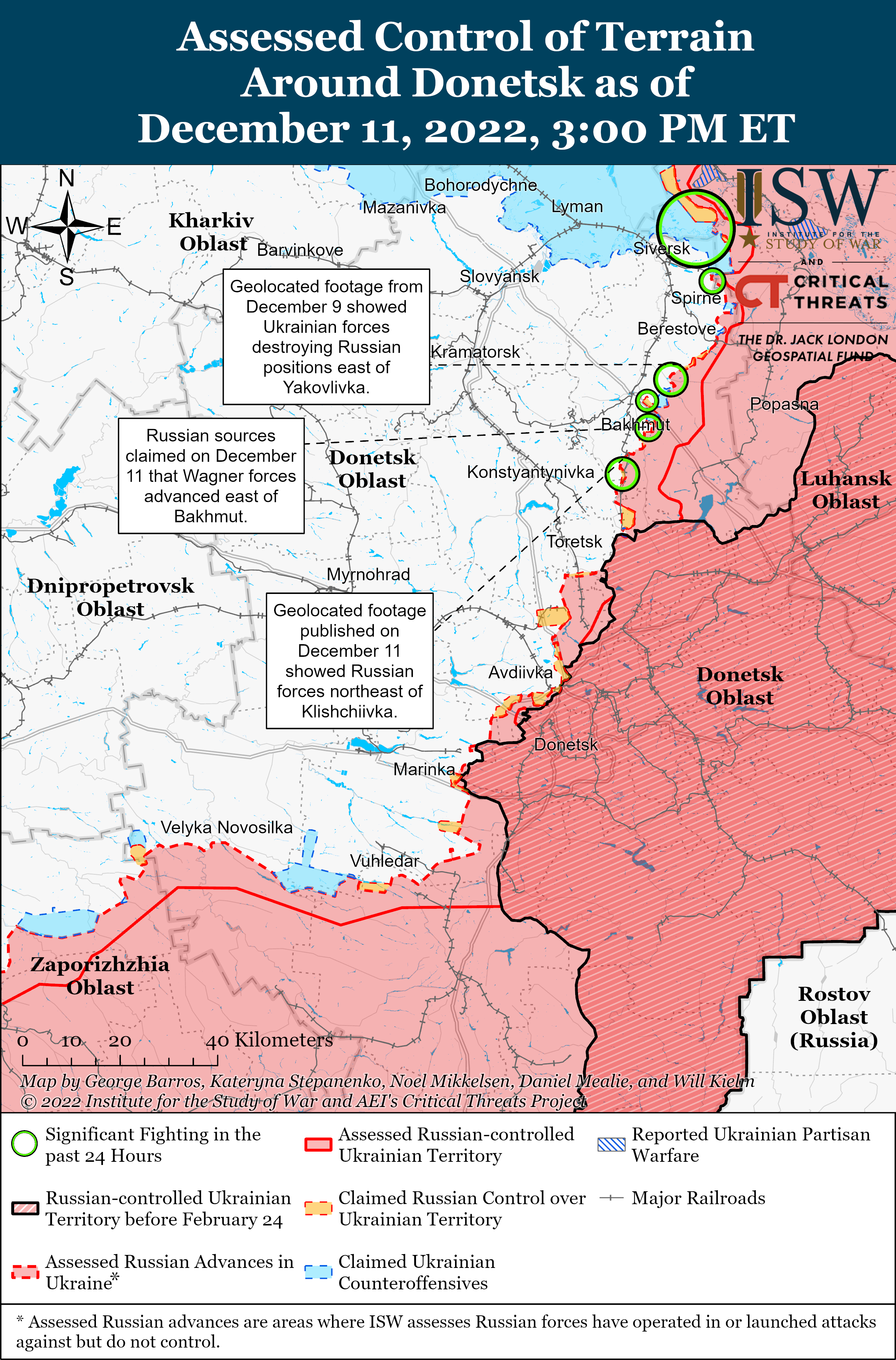

- Russian forces made marginal territorial gains around Bakhmut as Russian and Ukrainian sources reported continued fighting in the area.[42] A Ukrainian Armed Forces Eastern Group spokesperson stated that Russian forces changed tactics from using battalion tactical groups (BTGs) to smaller assault groups for offensive actions.[43]

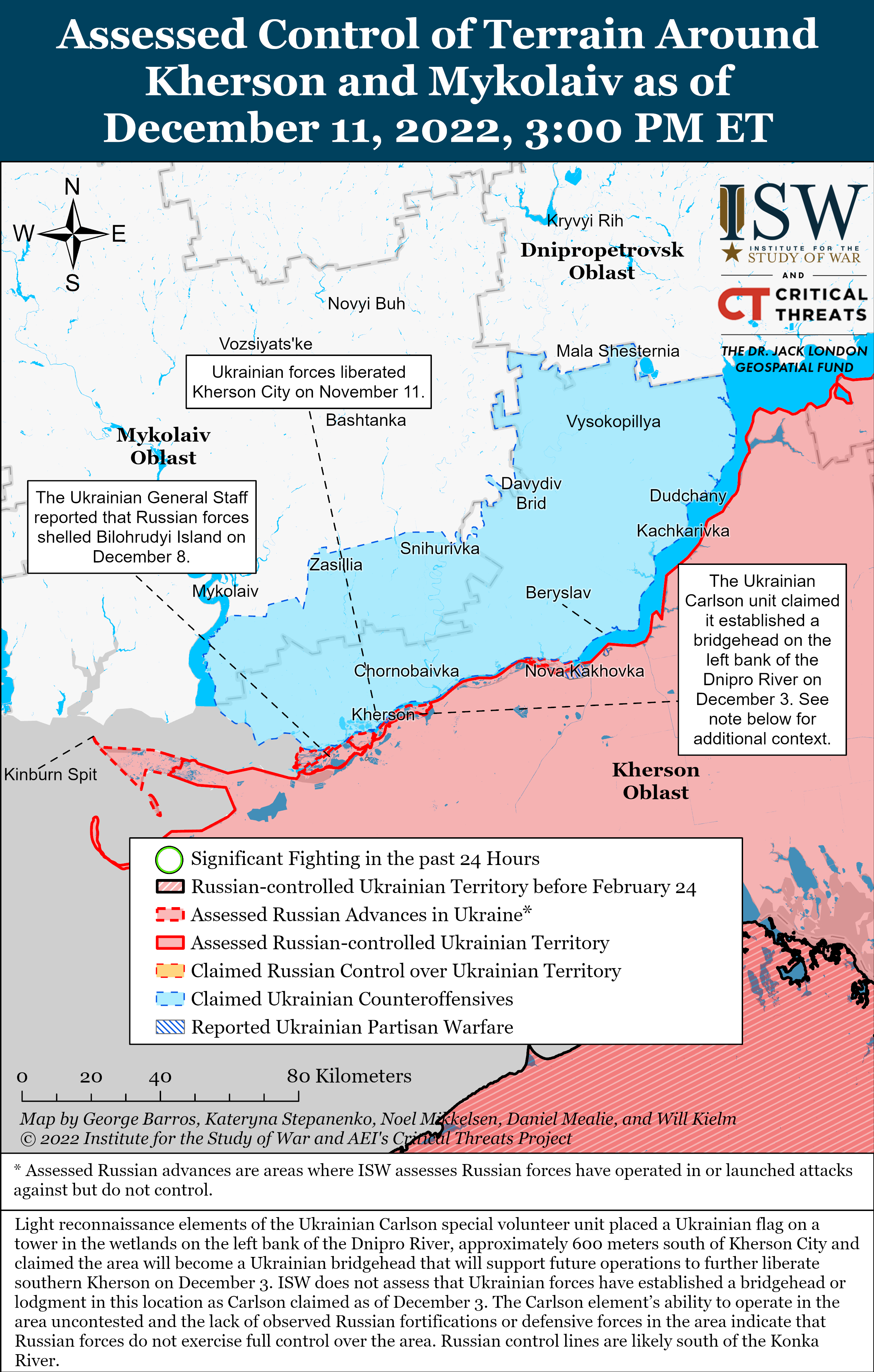

- Russian and Ukrainian sources claimed that Ukrainian forces struck Skadovsk, Hola Prystan, Oleshky, and Nova Kakhovka, Kherson Oblast, all along major Russian logistics lines.[44]

- Russian and Ukrainian sources reported that Ukrainian forces struck a Russian military base in Melitopol, Zaporizhia Oblast.[45] One source claimed that the strike killed up to 200 Russian military personnel.[46]

- Ukrainian officials reported that Russian occupation authorities intensified forced mobilization measures in occupied Ukraine.[47] Russiamil bloggersrs claimed that Russian forces face shortages of blood for wounded military personnel and are running donor drives in occupied Crimea.[48]

- A Ukrainian partisan group claimed responsibility for setting fire to a Russian military barracks in Sovietske, Crimea.[49] Ukrainian and Russian officials reported that Russian authorities continued filtration and law enforcement crackdowns in occupied Ukraine.[50]

References

[1] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/belarus-warning-update-for...

[2] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/belarus-warning-update-for...

[3]https://isw.pub/RusCampaignMar11 ; https://isw.pub/RusCampaignMar21 ;...

[4] https://isw.pub/UkrWar120322

[5] https://www.understandingwar.org/map/russian-forces-belarus-january-25-2...

[6] https://isw.pub/RusCampaignApr3

[7] https://isw.pub/RusCampaignOct11

[8] https://t.me/Hajun_BY/5792

[9] https://t.me/Hajun_BY/5830

[10] International Institute for Strategic Studies 2021 The Military Balance, 183-184 ( https://hostnezt.com/cssfiles/currentaffairs/The%20Military%20Balance%20...)

[11] International Institute for Strategic Studies 2021 The Military Balance, 183-184 ( https://hostnezt.com/cssfiles/currentaffairs/The%20Military%20Balance%20...)

[12] https://gur.gov dot ua/content/za-deiakymy-vydamy-ozbroiennia-rosiia-vzhe-vykorystovuie-stratehichnyi-zapas.html

[13] https://gur.gov dot ua/content/v-bilorusi-planuiut-nalahodyty-vyrobnytstvo-snariadiv-dlia-stvolnoi-artylerii-ta-rszv.html

[14] https://gur.gov dot ua/content/okupanty-prodovzhuiut-perekydaty-na-terytoriiu-bilorusi-dronykamikadze-shahed136.html

[15] https://t.me/Hajun_BY/5733

[16] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign... ; ; https://t.me/Hajun_BY/5717 ; ; https://t.me/Hajun_BY/5900 ; https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid0RdkUN4VDMb4WU8WgfzG... ; https://t.me/mod_russia/22459 ; . https://t.me/mod_russia/22459

[17] https://t.me/Hajun_BY/5597 ; https://motolko.help/ru-news/komplektovanie-srochnikami-vs-rb-kakim-roda... ; https://primepress dot by/news/ekonomika/otpravka_v_voyska_prizyvnikov_osennego_prizyva_nachalas_v_belarusi-39008/

[18] https://t.me/Hajun_BY/5888

[19] https://gur dot gov.ua/content/v-bilorusi-hotuiutsia-pryiniaty-20-tysiach-mobilizovanykh-z-rf.html

[20] https://sprotyv.mod dot gov.ua/2022/11/25/rosiyany-prodovzhuyut-rozgortaty-vijska-v-bilorusi/

[21] https://isw.pub/UkrWar112822

[22] International Institute for Strategic Studies 2021 The Military Balance, 183-184 ( https://hostnezt.com/cssfiles/currentaffairs/The%20Military%20Balance%20... )

[23] Russia’s Zapad-2021 Exercise | Institute for the Study of War (understandingwar.org) ; Russia in Review: Russia Opens Permanent Training Center in Belarus and Sets Conditions for Permanent Military Basing | Institute for the Study of War (understandingwar.org)

[24] Russia’s Zapad-2021 Exercise | Institute for the Study of War (understandingwar.org)

[25]https://isw.pub/RusCampaignOct3;https://isw.pub/RusCampaignOct10 ;https://isw.pub/RusCampaignApr3; https://isw.pub/RusCampaignJune8

[26] https://isw.pub/RusCampaignOct10

[27]https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid08ERrBJJor2mUkZyp3z7...

[28]https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid02YCSX87CsqK2udvjM2z...

[29] https://gur.gov dot ua/content/sered-rosiiskykh-chastkovo-mobilizovanykh-u-bilorusi-spalakh-zakhvoriuvan-cherez-nedotrymannia-sanitarnykh-umov.html

[30] https://edition.cnn.com/interactive/2022/10/europe/belarus-hospitals-rus...

[31] https://twitter.com/franakviacorka/status/1497911200692289544

[32] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[33] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[34] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/belarus-warning-update-kre... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/belarus-warning-update-vio... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/belarus-warning-update-opp... ; https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/belarus-warning-update-bel...

[35] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vLG2IZaEQf0; https://armyinform.com.ua/2022/11/24/10-15-tysyach-biloruskyh-sylovykiv-...

[36] https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign...

[37] https://isw.pub/RusCampaignAugust21

[38] https://t.me/readovkanews/48710; https://t.me/swodki/201791; https://t.me/notes_veterans/6986; https://t.me/voenkorKotenok/43559; https://t.me/arnamax/6304; https://t.me/mig41/22438; https://t.me/mod_russia/22588

[39] https://t.me/vysokygovorit/10249; https://t.me/vysokygovorit/10250; https://t.me/miroshnik_r/9827; https://t.me/NeoficialniyBeZsonoV/20536; https://t.me/vysokygovorit/10253; https://t.me/stranaua/79881; https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid02BaPRkC1tPp53SEWzh7...; https://t.me/mod_russia/22572; https://t.me/wargonzo/9704

[40] https://twitter.com/Danspiun/status/1601718010162839552; https://t.me/notes_veterans/6984

[41] https://t.me/stranaua/79876

[42] https://t.me/mod_russia/22572; https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid02BaPRkC1tPp53SEWzh7...; https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid026zZzZfMLuTFAs1uGTQ...; https://twitter.com/neonhandrail/status/1601883386943246337

https://twitter.com/PaulJawin/status/1601856772049965056; https://t.me/robert_magyar/239

https://twitter.com/PaulJawin/status/1601688657316175873

https://twitter.com/EerikMatero/status/1601696466200059904; https://twitter.com/PaulJawin/status/1601675015619248128

https://twitter.com/blinzka/status/1601684321814728704; https://t.me/Bratchuk_Sergey/24517; https://t.me/rlz_the_kraken/54951; https://t.me/boris_rozhin/72569; https://t.me/brussinf/5367; https://t.me/wargonzo/9704;

[43] https://armyinform dot com.ua/2022/12/11/na-bahmutskomu-napryamku-okupanty-zminyly-taktyku-vedennya-bojovyh-dij-sergij-cherevatyj/

[44] https://t.me/readovkanews/48700; https://t.me/readovkanews/48663; https://suspilne dot media/336006-pivtora-miljona-ludej-na-odesini-bez-svitla-es-pogodivsa-nadati-18-milardiv-ukraini-291-den-vijni-onlajn/; https://t.me/hueviyherson/30748

[45] https://t.me/mod_russia/22572; https://t.me/nm_dnr/9569; https://t.me/BalitskyEV/587; https://t.me/BalitskyEV/586; https://t.me/vrogov/6438; https://t.me/vrogov/6441; https://t.me/vrogov/6432; https://t.me/readovkanews/48671; https://t.me/wargonzo/9701; https://twitter.com/neonhandrail/status/1601860410755682304

https://t.me/izvestia/114955; https://t.me/rybar/41913; https://twitter.com/IntelCrab/status/1601697039452364800

https://twitter.com/IntelCrab/status/1601682486861660161; https://twitter.com/666_mancer/status/1601825348404273153; https://twitter.com/666_mancer/status/1601703038640877568; https://twitter.com/zcjbrooker/status/1601702987654889472

https://t.me/rian_ru/188336; https://t.me/russkiy_opolchenec/35233; https://ria.ru/20221211/melitopol-1837856255.html;

[46] https://twitter.com/Militarylandnet/status/1601856383472881666

[47]https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/pfbid02BaPRkC1tPp53SEWzh7...; https://sprotyv dot mod.gov.ua/2022/12/11/rosiyany-aktyvizuyut-mobilizacziyu-na-tot/; https://t.me/luhanskaVTSA/7366; https://t.me/luhanskaVTSA/7367

[48] https://t.me/rybar/41912; https://t.me/dva_majors/6687

[49] https://t.me/atesh_ua/267

[50] https://t.me/nm_dnr/9570; https://www.facebook.com/sergey.khlan/posts/pfbid029vwMB4NrzykBNWV1NSsLo...; https://t.me/ivan_fedorov_melitopol/1022