SOURCE:

https://www.revistamilitar.pt/artigo/798

The Indian Ocean contains some of the most important global maritime shipping routes, particularly in the triangle Bab-el-Mandeb, Hormuz and Malacca Straits around the Indian peninsula. These sea routes account for 97% of India’s external trade[10].

The relatively small amphibious capability relies on the INS “Jalashwa”[43] capable of taking up to 900 troops and two “Magar” class ships with bow door and ramps (able to carry 200 troops, 16 tanks and one helicopter), seven landing ships “Kumbhir” class (carries up to 140 troops and 350 tons of cargo) and a two landing crafts. It is planned to follow the “Magar” class with larger amphibious ships with docks but the deadline is unknown. At this moment, due to “Magar” class ship’s short range, lack of spare parts, ageing and the material conditions, the amphibious capability should be considered very limited.

https://www.revistamilitar.pt/artigo/798

MARITIME : INDIAN OCEAN

NAVAL POWER IN INDIA`S GEOPOLITICS

NAVAL POWER IN INDIA`S GEOPOLITICS

Capitão-de-fragata

Humberto Santos Rocha

Humberto Santos Rocha

Introduction

Maritime interests in the Indian Ocean are related with the major sea trade routes from Asia and Middle East besides the effective and potential richness of sea-related maritime activities, where energy concerns are also of major importance. This increasing importance of the maritime issues made several Asian countries to develop security policies in order to protect them, thus bringing differing objectives which sometimes collide at the international and economic relations level.

For centuries India fought, not only the continental disputes with some of its neighbouring countries, but also, various naval fights where the naval power, under political guidance, contributed for the maritime objectives.

Still today, Indian naval power is the military component that strategically defends India’s maritime interests in a region still suffering major geopolitical changes and where the clash of some economic issues and political decisions consequences are still unknown.

This study is developed in two different parts: a characterisation of India’s maritime interests and the comprehension of the Indian naval power, leading to the analysis and conclusions on its impact on India’s geopolitics.

1. India’s Maritime Geopolitics

In order to build an Indian maritime geopolitics analysis, an approach to India’s Geography and geopolitics is propounded, likewise other global and regional players and respective strategic maritime interests, all within a maritime context.

a. Geography and geopolitics within the maritime context

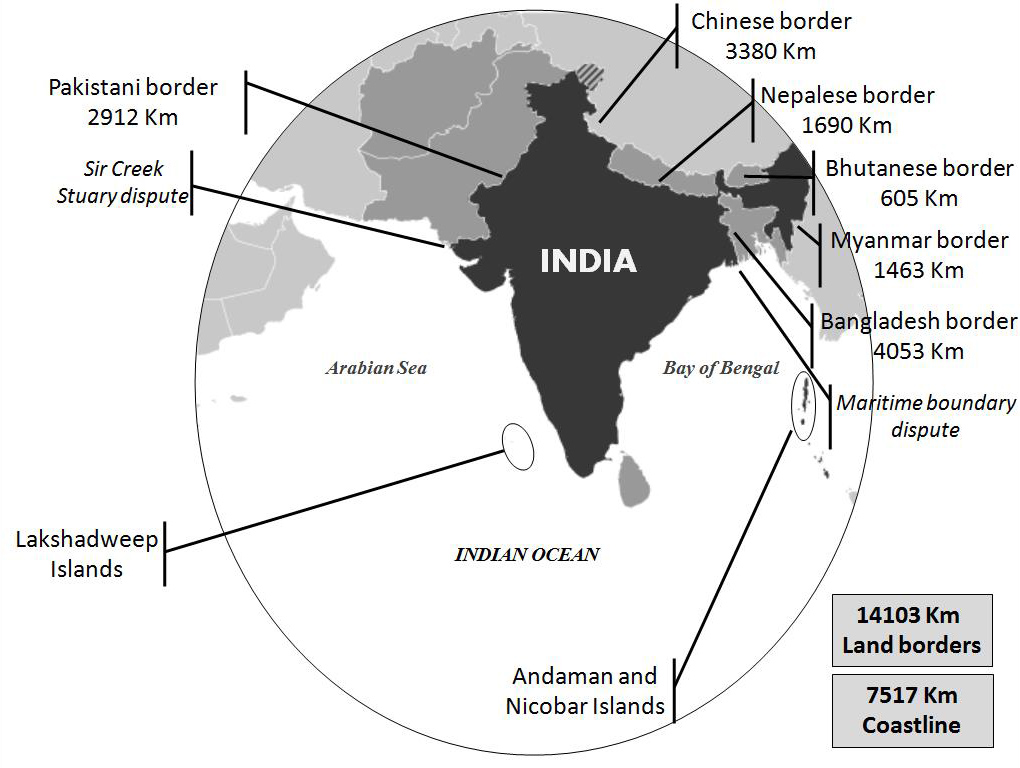

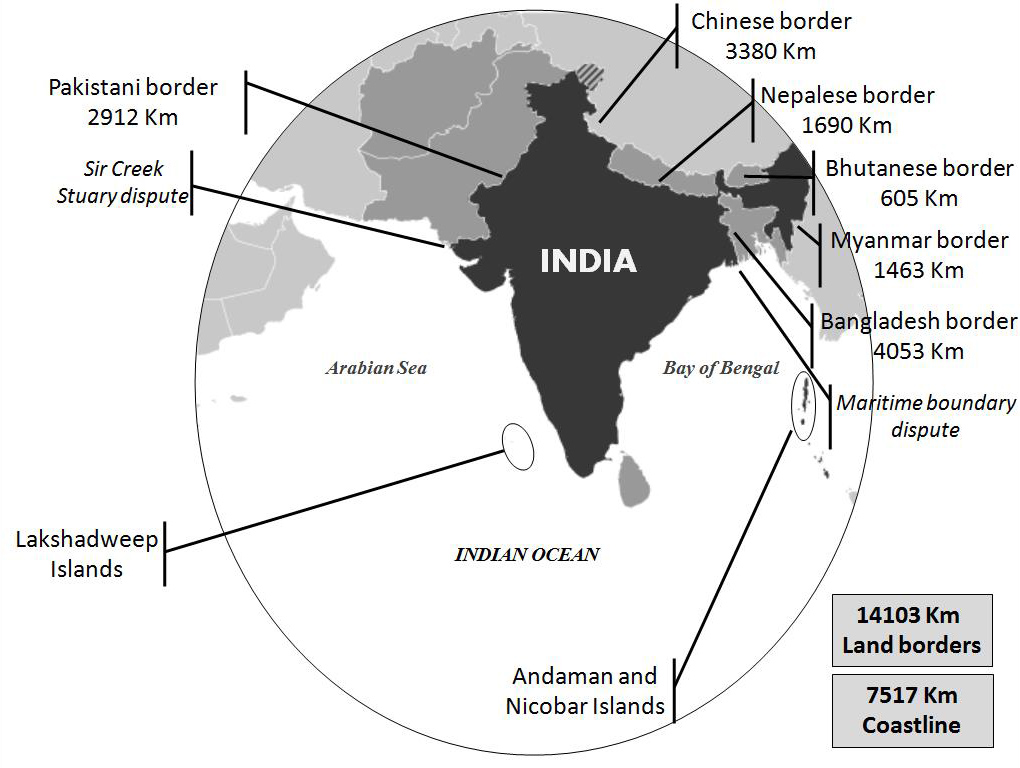

India has a large area of more than 3 million square kilometres in the Indian peninsula and in more than 1.000 island territories. It has over than 14.000 kilometres land borders with Pakistan, China, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar and Bangladesh and more than 7.000 kilometres of coastline having maritime boundaries[1] with Maldives, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Indonesia, Thailand, Pakistan and Bangladesh. The maritime borders are shared with more countries than those with which it has land borders[2].

There are presently two maritime disputes with Pakistan in Sir Creek Stuary and with Bangladesh due to maritime boundaries overlapping issues. These disputes have not been a priority in the political agenda of both countries, maintaining the status quo while political negotiations are addressed[3].

Besides the continental territory there are more than 300 inhabited island possessions, including the Lakshadween and Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

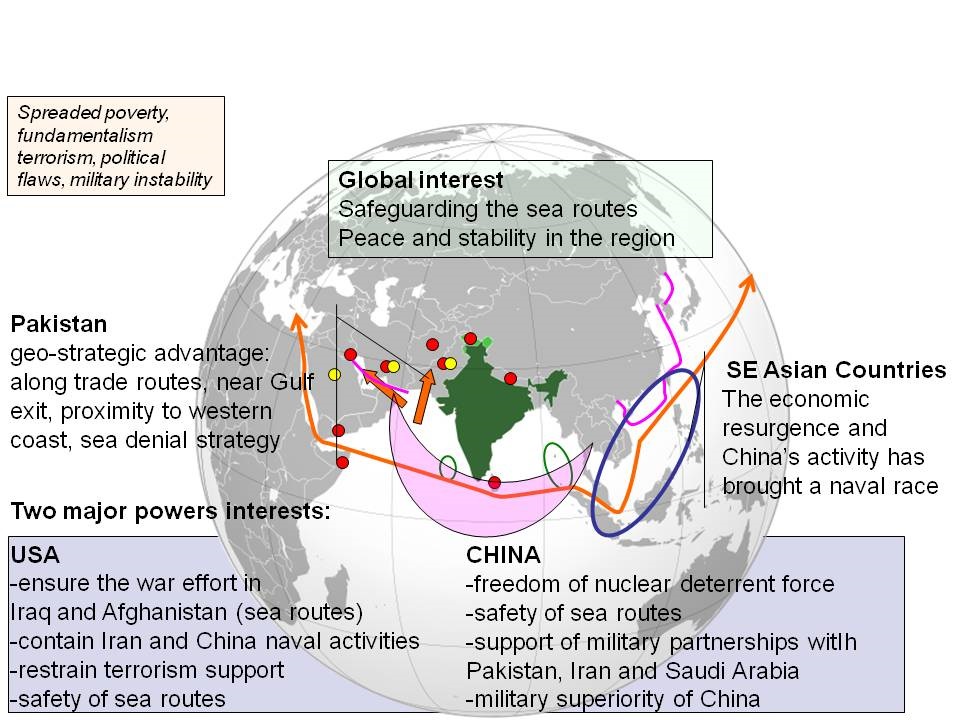

Many India’s bordering countries and several Indian Ocean coastal States are scattered with harsh problems like poverty, extremism, terrorism, political flaws and military instability particularly to the west, in countries such as Somalia, Yemen, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Myanmar and Sri Lanka among others, which can threaten peace and stability.

Map 1 - India's territories, land borders, and coastline and maritime disputes[4].

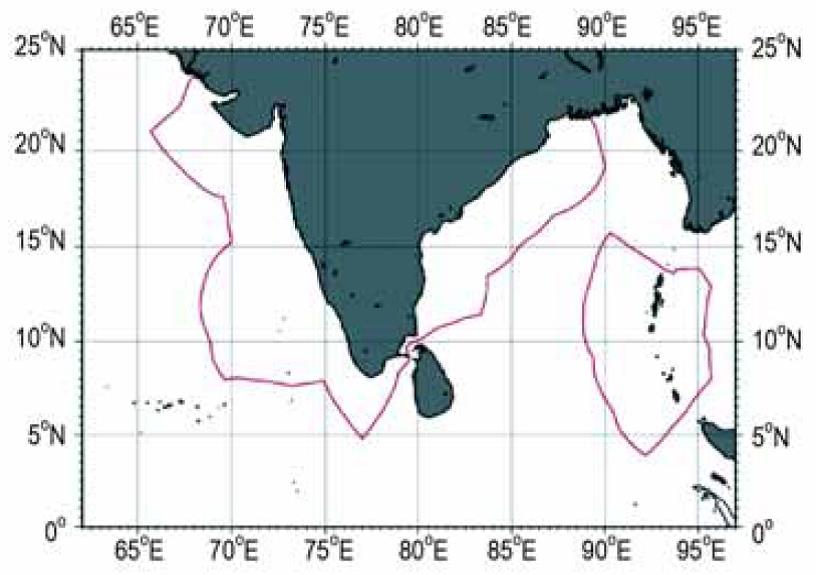

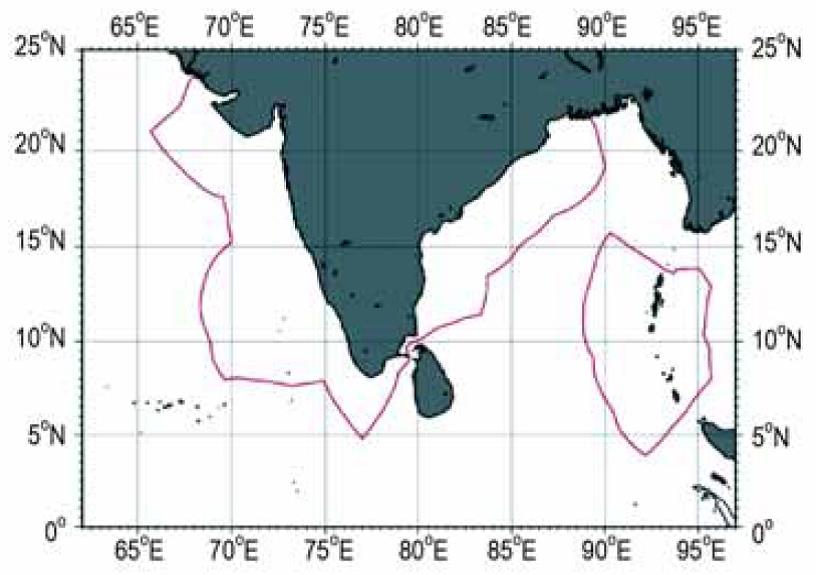

It should be noted the importance of the the Lakshadween and Andaman and Nicobar Islands as far as maritime geopolitics is concerned, as it enables India to have a wide exclusive economic zone (EEZ)[5], besides the possibility of being used as forward military base for power projection[6].

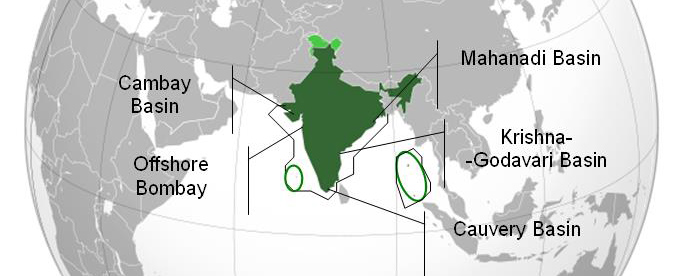

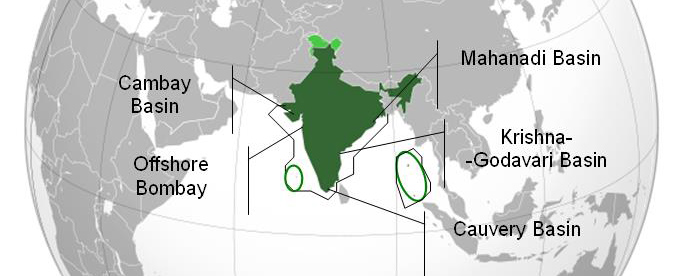

There are several oil and gas offshore facilities, mainly in the western coast which account for two-thirds of the domestic production[8].

Map 3 - Most relevant oil and gas offshore facilities areas[9].

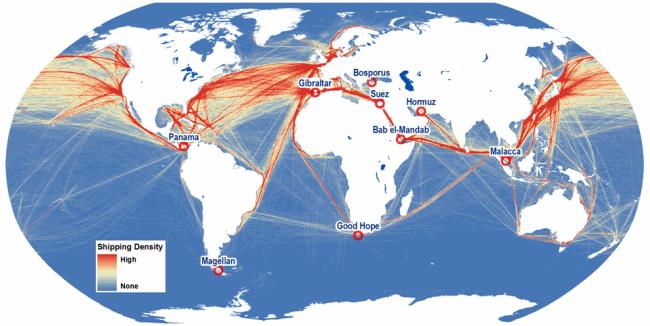

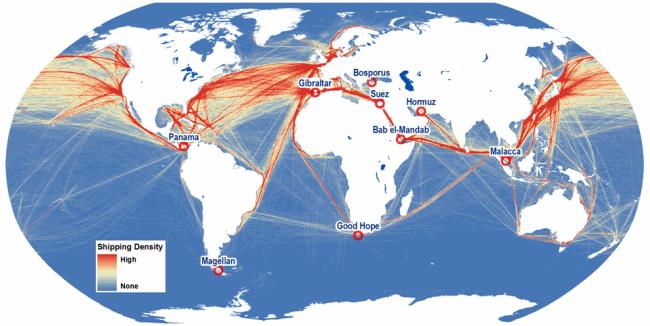

The Indian Ocean contains some of the most important global maritime shipping routes, particularly in the triangle Bab-el-Mandeb, Hormuz and Malacca Straits around the Indian peninsula. These sea routes account for 97% of India’s external trade[10].

Other relevant facts that state the importance of these routes are India’s importations by sea of oil and gas, being presently the world fifth largest oil consumer[11] and the sixth largest crude importer[12]. Thus, these routes are of outmost strategic importance.

Map 4 - Global sea trade routes and choke points[13].

Even though India’s ports being spread around allcoast[14], they are customary, stranded and non-efficient. There are high expectations on the investments in modernization, personnel and cargo handling technology, though. As a reference, it can take up to 21 days to dispatch sea cargo. By reducing this time, costs would be reduced, thus increasing exportations. The overall cargo transported through Indian harbours during 2004 and 2005 was 510 million tons while it is expected an overall cargo transportation of about 1000 millions tons for 2010[15].

Geographically, several of these ports, particularly the southernmost ones, are quite well placed, aligned with one of the most important maritime shipping route.

(b). Global and Regional Powers in Southern Asia Geopolitics

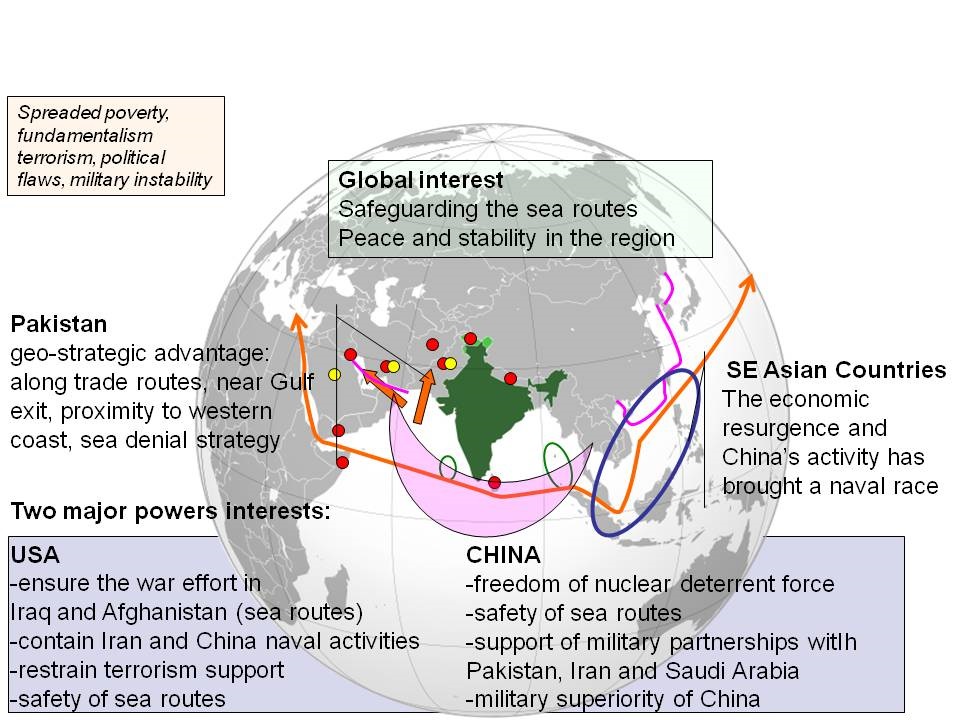

Two major powers with high interests in southern Asia and Indian Ocean are the United States of America and China.

United States, keeps the interest in containing, militarily, North Korea, Iran and China (in support of Taiwan), while it has to support the operations in Iraq and Afghanistan still restraining terrorist supporting activities. Also the economic interest on keeping the safe flow from Persian Gulf and Central Asia hydrocarbons resources and the sea trading with Japan, China, Taiwan and Southeast Asia is of outmost importance.

On the other hand, China looks for the safety of its nuclear deterrent naval force, the safety of its sea trade routes to the west and also the long lasting desire to reunite Taiwan with China[16]. For this, China has established military partnerships with Pakistan, Iran and Saudi Arabia[17]. On the military side, China can count with its own building capacity of aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines and armament.

Therefore it is crucial for India to have a strong and credible maritime and naval capability.

Although it can not have the ambition of superseding the other two major powers, it can at least increase the stake when/if a conflict emerges.

Although it can not have the ambition of superseding the other two major powers, it can at least increase the stake when/if a conflict emerges.

Regarding Pakistan, the long historical disputes have brought permanent worries as far as the international relations between India and Pakistan are concerned. India has all the interest that Pakistan maintains its political stability and anxiously expects it improves its security and economic prosperity.

Pakistan has a geo-strategic benefit concerning its position along the trade routes off the Hormuz Strait, its proximity to the Gulf, the proximity of the Indian western coast and its sea denial maritime strategy based on a relevant submarine fleet.

On the eastern area, the economic resurgence brought a naval race in the region due to China’s activity and financial capacity[18].

Within this strategic and geopolitical scenario, India aims to “acquire war fighting capabilities to operate across the full spectrum of conflict”[19].

The deterrence concept, for itself, is to be considered as the capacity of inflicting considerable damages to an opponent, raising the stake of a confrontation and making the enemy to risk a total and unacceptable loss forcing him to refrain from his intentions. It does not assume the need of employing nuclear weaponry.

(c.) India’s Strategic Maritime Interests

It can be pointed that the main purposes of India’s Navy is to ensure national security and protection from external interference, fostering economic growth, security and well being.

In the recent past India has been a “status quo” power with no extra-territorial ambitions, but with some spread territories around its islands, has kept the capabilities of protecting them while also helping to protect its friendly neighbouring countries.

The recent booming economic growth is sustained by an increased trade and energy need, highly dependent on the sea by means of maritime security and undersea resources and for these reasons India has very strong maritime interests.

Therefore, it can be said that India’s seeks out the freedom to use the seas and to safeguard its maritime interests at all circumstances and for this it assumes military, diplomatic, constabulary and benign roles[20].

These strategic interests can then be summarized in the following table:

Interest

|

Areas

|

Considerations

| |

|---|---|---|---|

Economic

|

Sea trade routes security

|

Sea trade routes between the Persian Gulf to the Strait of Malacca.

|

Over 200 billion USD worth of oil in these routes. Ensuring the free flow of oil and commerce in the region.

|

Oil imports

|

Sea trade routes from the Persian Gulf to India

|

India imports about 70% of its consumption[21]. About 40% of overall consumption is ensured by sea.

| |

Sea resources

|

India’s coastline and Economic Exclusion Zone

|

India’s EEZ over 2 million square kilometres, the existence of hydrocarbon resources.

| |

Exportations and importations

|

Sea trade routes eastwards and westwards

|

India’s exportations valued in more than 75 billion USD. Importations are vital for basic economy needs

| |

Economic and military

|

Merchant fleet and ports

|

Indian Ports and operation areas of merchant ships

|

Indian merchant fleet accounts for a considerable part of the Indian sea trade[22], being a strategic issue on the maritime security plan. In addition, ports security, are paramount for all trade.

|

Oil production

|

Trincomalee, Sakhalin Islands, Egypt, Sudan and Myanmar

|

India’s oil companies operating in these countries.

| |

Military

|

Territorial security

|

India’s mainland and islands

|

Vital territorial defence.

|

Table 1 - India's strategic interests, areas and other considerations.

(d.) Indian Ocean, India and major powers geopolitical chessboard

It can be drawn now, as a way of summarizing what has been said, a geopolitical chessboard where India and also other major powers act, based on:

- the geographic characteristics of the continental and insular territories;

- the security, peace and stability threats from poverty, political flaws and military instability in several surrounding countries;

- the importance of the sea lines of communication between Hormuz, Bab-el-Mandeb and Malacca with global impact;

- Pakistan geo-strategic advantage from its proximity to Hormuz Strait, Indian western coast and its sea denial capability;

- United States and China interests;

- Global interest of safeguarding the routes and ensure peace and stability in the region.

Map 5 - Indian Ocean and India's geopolitical chessboard[23].

In this chessboard, India’s maritime interests can be summarized in:

- its coasts and island possessions;

- the EEZ;

- sea routes;

- gas and oil offshore facilities;

- maritime facilities;

- Indian shipping activity;

being the naval power the military instrument that contributes for the use of the sea by applying force or coaction, assuming the sea as a manoeuvre theatre.

2. India’s Naval Power

A characterisation of the Indian naval power should now be presented so its role on India’s interests and geopolitics be analyzed.

A simple, yet common, definition of naval power, states the “naval power as the military instrument of the sea power or the component of the military power that uses the sea as manoeuvre theatre”[24].

The concept adopted in this study is the “naval power as all the assets, mainly military, that a country has for contributing by coercion and use of force, under political guidance, for the maritime objectives ensuring the use of the sea”.

In countries like India that have both Navy and Coast Guard, the Navy is usually committed with military tasks, while Coast Guard with constabulary roles in peace time, but the latter can also act as a military reserve mainly for coastal protection in a conflict, thus contributing for the maritime objectives ensuring the use of the sea.

(a.) Indian Naval Power Background

India’s naval activity evolution can be traced back to the antecedents of India’s maritime activity early in 2300 b.C. during the Harappan civilization[25].

During the 5th and 10th centuries A.D., the southern and eastern kingdoms ruled over Malaya, Sumatra and Western Java being the Andaman and Nicobar Islands important naval and commercial bases for trading with those kingdoms and China.

In the 10th century, Chola kings sent out naval expeditions to fight piracy from Sumatran warlords and control the straits of Southeast Asia[26].

The decline of Indian maritime power started in the 13th century due to the continental threats superseding the maritime endeavours. This decline was later stressed by the arrival of the Portuguese in the 15th century and other European navies later on[27].

Indian navy origins in the modern times started in 1612 with the establishment of the Indian Marine for the defence of the East India Company’s sea routes[28].

In 1932 the Royal Indian Navy was formerly established under the control of the British Royal Navy[29].

Before the independence, the importance of the Indian Navy was hampered due to the Royal Navy prominence, until the Second World War and the occupation of Myanmar, Andaman and Nicobar Islands and parts of northeast India as well, by Japan. The need of shipbuilding, personnel recruitment, training and naval facilities forced bases to be built and a massive recruitment to be conducted.

With the separation of India and Pakistan, Royal Indian Navy lost about one third the size and assets in the division[30].

After the independence, the expansion of India’s Navy can be separated in three phases: 1947-1962, 1962-1980 and 1980-present day.

In the first phase, after the recognition of the importance of the navy in the future role of India in the Indian Ocean, it was established a plan to form two fleets, each one with an aircraft carrier, a submarine force and an air arm. The ambitious plan had several setbacks due to lack of resources and the fact of facing greater threats from land with Pakistan and China tensions rather than from the sea.

Only in 1961 would India receive its first light aircraft carrier the INS “Vikrant”[31] bought from England.

A second phase, is pointed after the India-China war in 1962, where the navy allocations were drastically reduced, being the army and air force the defence priorities.

This situation was altered with the India-Pakistan war in 1965, where Indian Navy presented a maritime disadvantage against Pakistan which relied on a modern fleet and help from the United States that threatened the merchant and naval fleet in Arabian Sea as well as in Bay of Bengal. Also, the fact that Pakistan had a submarine, which effectively carried out sea denial, and the emergence of an axis Pakistan-China-Indonesia, forced India to reconsider the role of its navy, establishing a plan where submarines became top priority.

The submarines acquisition was a hard toil as no western country was interested in such plan, making India to call for help from the Soviet Union. That marked the beginning of the Indian-Soviet military relation that would allow India to turn itself into one of the biggest navies in the Indian Ocean.

In 1968, with the acquisition of the attack submarines, a navy grew a fresh new importance for being able to play a role far beyond the shore defence. That was the result of the 1960s doctrine and plans which preceded the submarine acquisition and the indigenous frigates fitted with missiles that would, later in the 1971 during the Indian-Pakistani, help the victorious outcome to India.

During the 1970s, the navy earned the legitimacy for the naval expansion based on the naval superiority won against Pakistan and the readiness to assume greater responsibilities: ensure sea denial and sea control responsibilities making it to emerge as the largest navy in the Indian Ocean during the 1980s.

The Indian Coast Guard was established in 1978 with the objective of playing a crucial supportive role in a conflict situation.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, India acquired a second aircraft carrier, long-range maritime aircraft, operated a leased nuclear submarine and established plans to acquire modern conventional submarines from the Soviet Union and Federal Republic of Germany, while building several of its own surface units and submarines later on[32].

(b.) Indian Naval Power Today

Indian Navy is considered the fifth largest navy as far as personnel is concerned, with about 55.000 men.. This number includes approximately 5.000 men in the naval aviation branch, about 2.000 special operations men and 1.000 men from the Sagar Prahari Bal, a special wing for shallow waters patrols including search and rescue. The Coast Guard has about 5.500 men.[33]

As a comparison with other Indian military branches, it is by far the shortest, as the air force has about 170.000 and the army more than 1 million soldiers[34].

(c.) Indian Navy, Vision, Missions, Roles and Organization

The navy, in accordance with its “vision” is “determined to create and sustain a three dimensional, technology enabled and networked force capable of safeguarding our [Indian] maritime interests on the high seas and projecting combat power across the [Indian Ocean] littoral, (…) [seeking] to evolve relevant conceptual frameworks and acquire war fighting capabilities to operate across the full spectrum of conflict. The Indian Navy will also be prepared to undertake benign and humanitarian tasks in (…) the maritime neighbourhood, whenever required”[35].

The highlights of this vision are:

- “three dimensional” that is air, surface, and under water;

- “maritime interests” which have already been thoroughly identified;

- “operate across the full spectrum of conflict”, which commonly ranges from humanitarian operations to unlimited nuclear conflict, being somehow too ambitious.

As stated, this is the navy’s own vision, which for itself does not grant these capabilities but for some of them just an endeavour.

India’s Navy mission can be typified by: protect the coastlines, its island possessions, the economic exclusion zone and the important sea lines of communications around its territories[36], counting on its blue water navy assets: submarines, oceanic surface ships and aircraft.

The protection of the sea lines of communications, ensure to India the safety of its own maritime economical interests thus its own regional strategic importance, contributing for its neighbours own welfare.

The Indian Navy is headed by the Chief of Naval Staff and has four commands: the Western Naval Command, the Eastern Naval Command the Southern Naval Command and the Far Eastern Naval Command.

The Western Naval Command and the Eastern Naval Command, based in Mumbai and Visakhapatnam, respectively, are in charge of all the naval operations in the western and eastern coasts.. The Southern Naval Command, based in Cochin, is responsible for the naval operations in the southern coast (from the latitude of Goa to the Palk Straits and also for all the navy training functions.

Based in Port Blair, there is the recently created (2001) Andaman and Nicobar Command, which is planned to be fully operational by 2012, derives from the Eastern Naval Command and it includes now the Andaman and Nicobar Islands..

(d.) Naval Facilities and Shipyards

The homeports of each Command (Western, Eastern, Southern and Andaman and Nicobar) are also the base of several naval support facilities.

In the Western Coast, Cochin homes a naval air station, a shipyard and naval schools. In Goa, there are some naval air facilities, a small shipyard (capable of patrol boats and landing crafts shipbuilding) and the Indian Naval Academy as well.

Mumbai naval facilities include a large shipyard with docks for aircraft carriers, submarines and the construction capability up to submarines and destroyers.

In the Eastern Coast, it is located the submarine base (in Visakhapatnam), the submarine school, other recruits schools, and a major repair and construction shipyard, including for amphibious ships.

There are three warship naval shipbuilding shipyards in Mumbai, Calcutta and Goa. Other three shipyards, in Calcutta Visakhapatnam and Cochin are able to build naval ships[37]. The main military shipyard, able to build military ships up to 7.000 tons, is located in the Mazagon Dockyard Ltd in Mumbai , and has already built several surface units and submarines.

All these six shipyards run within the public sector industries and ensure India the complex shipbuilding capability like submarines and destroyers aiming still the ambitious project of building the future Indian aircraft carrier.

Along its island territories, there are also many facilities including naval bases, naval air stations (like in Port Blair) and support facilities.

Map 6 - Indian naval establishments[38].

(e.) Aircraft Carrier and Surface Fleet

The only Indian aircraft carrier, presently the INS “Viraat”[39], is now an old ship, built in 1957 though still combat-worthy due to several upgrades taken[40].

India had plans to build an aircraft carrier by the end of the 1990s, which at the moment has not been completed. In 2009, India bought from Russia the aircraft carrier “Admiral Gorshkov” now INS “Vikramaditya” expected to be in service by 2012. There have been several attempts of edifying native capacity of building the aircraft carriers but until now that was not achieved.

It should be considered that for ensuring permanently one aircraft carrier available, there should be at least three[41], and presently India has in fact only one which will have its own training and maintenance periods compelling large inoperative periods.

India has for long, large experience on building and operational use of surface units, up to destroyer types[42]. Many of the current surface vessels were built in India, including the destroyers of the “Delhi” class and frigates of the “Godavari” and “Talwar” class.

The recent project 15, achieved the success of building a 6.500-7.000 tons displacement destroyer (INS “Mumbai”, INS “Delhi”, INS “Mysore”) with Indian design, able to carry up to two helicopters. The propulsion system, sensors and weapons included many state-of-the-art foreign companies and several native companies building under license.

Twenty of the overall twenty four corvettes are fitted with anti-surface missiles, thus being a considerable capability for sea control.

The relatively small amphibious capability relies on the INS “Jalashwa”[43] capable of taking up to 900 troops and two “Magar” class ships with bow door and ramps (able to carry 200 troops, 16 tanks and one helicopter), seven landing ships “Kumbhir” class (carries up to 140 troops and 350 tons of cargo) and a two landing crafts. It is planned to follow the “Magar” class with larger amphibious ships with docks but the deadline is unknown. At this moment, due to “Magar” class ship’s short range, lack of spare parts, ageing and the material conditions, the amphibious capability should be considered very limited.

The sustainability of the surface units at sea is ensured by three fleet tankers via replenishment at sea capability. Considering the cycle encompassing the maintenance, training and operational phases every ship must go through, the existence of only three fleet tankers causes to bestow limited sustainability to the fleet.

There are about 14 minesweepers, which should provide enough protection to India’s ports and major sea lines of communication. The minesweepers fleet is impressively large when compared with the whole navy fleet.

(f) Submarine Fleet

The navy counts with a large fleet of 16 conventional[44] submarines. The submarine construction capacity was achieved in the 1980s representing a relevant naval military construction capability. Submarine’s fleet size along with the fact that the submarines are still the only truthfully “invisible” assets. By being very deterrent (even a conventional one) the submarine threat becomes very relevant and credible[45]. Also, India is engaged on constructing six modern French Scorpéne class, in Mumbai.

India has for long sought to have nuclear submarines[46], firstly as an Indian-built project, but due to technology constraints, the project changed to look for Soviet help (by 1984). In 1991, the navy stated that the project of the nuclear submarine was based on the adaptation of a “Charlie-II” class submarine project from Russia. The first nuclear Indian submarine, INS “Arihant”, started sea trial in 2009. It is not clear when/if this submarine will have nuclear striking capabilities, though that is for sure an endeavour[47] either in this same project or in future ones[48] and it represents a huge step ina long journey towards a desired nuclear deterrence capability.

(g.) Naval Aviation

The first naval aircraft started operation in 1953, firstly shore based and only later, in 1961, Indian Navy started to operate aircraft and helicopters from ships.

The naval air arm is composed by Air squadrons, divided in two types: a front line comprising fighters, strikers, anti-submarine warfare fixed wing and helicopters, logistics and unmanned air vehicles and a second line comprising the training duties.

Presently there is one fighter air squadron, nine maritime reconnaissance and anti submarine squadrons, one for logistical and communications support and three training squadrons[49] which can be very effective in surface search, surveillance and anti-submarine warfare as well up to 500 miles.

The following table contains a brief overview of the Navy fleet:

Classification[50] and number of assets

|

Main characteristics

| |

01

|

Aircraft carrier

|

INS “Viraat” is a tactical aircraft carrier that operates fighters and has striking aircraft capabilities for fleet air defence and helicopters for reconnaissance, patrol and anti-submarine warfare. Operates up to 30 fixed wing aircraft (usually takes only 12) and seven helicopters.

|

16

|

Conventional submarines

|

4 submarines are German built (variant of Type 209 class), 10 Kilo class and two ageing Foxtrot class now used for training purposes. 6 Scorpéne class are being built in Mumbai, not being expected the first one, to be ready before 2015.

|

07

|

Destroyers

|

Indian built (since 1983), equipped with SSM, SAM and organic helicopters. Blend eastern and western sensors and weapons

|

08

|

Frigates

| |

23

|

Corvettes

| |

06

|

Offshore Patrol Vessels

|

Equipped with guns and up to one helicopter, two of them are fitted with SSM and SAM

|

02

|

Missile Crafts

|

Fitted with SSM and SAM

|

12

|

Minesweepers

| |

08

|

Amphibious and landing ships

|

INS “Jalashwa” (2007) carries up to 900 troops and two “Magar” class ships carries up to 200 troops.

|

03

|

Fleet auxiliaries

|

Suited for RAS, are vital assets to ensure sustainability of naval forces at sea and expeditionary capability.

|

14

|

Fast Attack Crafts

|

Coastal crafts suited with guns.

|

Table 2 - Indian Navy fleet: classification, assets and main characteristics[53].

The major highlights from a comprehensive approach of the fleet and current projects are:

- the endeavour for having two aircraft carriers, though three are considered necessary;

- the large and credible escorts fleet, Indian built;

- the submarine fleet, in fact the invisible weapon, is large, credible and partially Indian built;

- the naval aviation:

- land based: effective for surface and submarine warfare up to 500 miles from coast;

- carrier based: depends on carrier being operational;

- destroyers/frigates based: organic helicopters for anti-submarine and anti-surface warfare are used as medium-range forward sensor and weapon, essential for naval forces self-defence and as complements of land-based aircraft missions;

- amphibious capability: despite the upgrade with INS “Jalashwa”, it is still small but heavily backed up by strategic airlift which for itself does not substitutes amphibious assets;

- considerations specifically related with the naval operational output concerning the three major phases of the operational cycle: maintenance / training operation which can take several months (or even years).;

- The fact that one aircraft carrier, one large plus two medium amphibious ships are insufficient for keeping a all-year round ready or high readiness single unit;

- The effective capacity of submarines either conventional or nuclear, to deter a naval force because of its lethality and being very hardly detected.;

- The projects are vulnerable to several setbacks;

- Even if a project is only at an “endeavour stage”, it should be taken into account as a long-term objective… which does not mean it will be accomplished.

Finally, apart from the the analysis of the military assets and overall performances by its characteristics (size, number, weaponry, capacities, interoperability, “command and control and communications”), the maintenance standards, logistic support, training skills and servicemen morale, dictate the effective operational outcome, which can largely distort the results and efficiency of the fleet[54].

Conclusions

All along this article, it was pointed out India’s maritime strategic interests, which were drawn on an area of interest around the peninsula, containing all territories and maritime trade routes between Hormuz, Bab-el-Mandeb and Malacca.

The maritime geopolitical chessboard includes the Pakistan located strategically in the exit from the Persian Gulf (and near India’s western coast where a large portion of its industrial and military capacity is placed) as well as the United States and China players.

The following key considerations and interests for India, regional and global players were identified as follows:

- the safety of the trade routes and ports is a vital way to ensure trade and provisions;

- the booming economic growth is sustained by an increased trade and energy needs,

from where we can conclude:

India’s naval power is prepared for its present missions, regarding the present opponents and situation status quo, with a credible non-nuclear deterrence capability. “It can defend what it has to defend”;

India’s naval power has evolved along with the Maritime Strategy, showing flexibility, preparedness and capability to overcome challenges;

The current naval projects when/if concluded will certainly boost the role of naval power;

“The operations across the full spectrum of conflict” presents itself as a very ambitious objective, as the current projects do not anticipate any change since none of them is planned to equip the fleet with nuclear weaponry;

Naval power can effectively protect current India’s maritime vital interests counteracting the prominence of other global powers in the region, contributing for the safety of regional critical issues, like the very crucial or maybe vital sea routes, with positive global impact.

Bibliography

Freedom to use the seas: India’s Maritime Military Strategy. Integrated Headquartes of the Ministry of Defence (Navy), May 2007.

|

The Indian’s Navy-Vision Document. Integrated Headquarters of the Ministry of Defence (Navy), May 2006.

|

ANANDA, Alok – Rise of Chinese and Indian Navies. Naval Despatch, September 2010.

|

CARTER, Clarence Earl – The Indian Navy: a military power at a political crossroads. Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air War College, Air University: 1996.

|

CLÉMENTIN-OJHA, Caherine; JAFRELLOT, Christophe; MATRINGE, Denis; POUCHEPADASS, Jacques – Dictionnaire de L’Inde. Larousse, 2009.

|

CURTIS, Lisa – U.S.-India Relations: the China factor. Massachusets: Backgrounder-Heritage Foundation, 2008.

|

KIYOTA, Tomoko – Playing at Hide-and-Seek: Submarines in Asian Navies

|

MONTEIRO, Eugénio Viassa – O Despertar da Índia. Lisboa: Aletheia Editores, Junho de 2009.

|

NAIDU, G. V. C. – Indian Navy and Southeast Asia. New Delhi: The Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis and Knowledge World, February 2000.

|

PANDA, Rajaram – Arihant-Stregnthning India’s Naval Capability. New Delhi: Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies-IPCS Issue Brief 115, September 2009.

|

ROY-CHAUDHURY, Rahul – Sea Power and Indian Security. London: Brassey’s, 1995.

|

SACHDEVA, Sanjay – Great Wall at Sea-Strategic Imperatives for India. Naval Despatch, December 2006.

|

SCHAFFER, Teresita; MITRA, Pramit – India as a Global Power?. Frankfurt: Deutsche Bank Research, 2005.

|

SINGH, Satyindra – Under Two Ensigns: the Indian Navy 1945-1950. New Delhi,: Oxford & IBH Publishing Co, 1985.

|

TILL, Geoffrey –Modern Sea Power, Vol. I. London: Brassey’s, 1987.

|

WATTS, Anthony J. – Jane’s Warship Recognition Guide. Harper Collins Smithsonian, 2006.

|

Other sources

Bharat-Rakshak – Indian Navy

http://www.bharat-rakshak.com/NAVY/

24th May 2010.

|

CIA-World Factbook

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/

27th May 2010

|

Federation of American Scientists – FAS ORG

http://www.fas.org/programs/ssp/man/militarysumsfolder/india.html

24th May 2010

http://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/india/sub/ssn/part01.htm

24th May 2010

|

Indian Navy

http://indiannavy.nic.in/welcome.html

24th May 2010.

|

Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses

http://www.idsa.in/

27th May 2010

|

Institute of Peace & Conflict Studies

http://www.ipcs.org

24th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/article_details.php?articleNo=2551

24th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=3061

24th May 2010

ttp://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=2854

24th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=2845

24th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=2503

24th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=2784

24th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=2979

24th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=3061

24th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=2378

24th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=1866

24th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=2379

24th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=218624th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=2852

24th May 2010

http://www.ipcs.org/print_article-details.php?recNo=2567

24th May 2010

|

Maps of India

http://www.mapsofindia.com/maps/india/sea-ports.htm

24th May 2010.

|

United Nations-cartographic section

http://www.un.org/depts/Cartographic/english/htmain.htm

24th May 2010.

|

[1] These maritime boundaries relate with the territorial sea, contiguous zone, exclusive economic zone, continental shelf,

[2] Freedom to use the seas: India’s Maritime Military Strategy, p. 59.

[3] Freedom to use the seas: India’s Maritime Military Strategy, p. 58.

[4] Base map source: CIA World Factbook 2010.

[5] The EEZ is the maritime area where the “coastal State has sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living, of the waters superjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil, and with regard to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone” (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea).

[6] SACHDEVA, Sanjay - Great Wall at Sea-Strategic Imperatives for India

[7] Freedom to use the seas: India’s Maritime Military Strategy, p. 59.

[8] CARTER, Clarence Earl - The Indian Navy: a military power at a political crossroads, p. 4.

[9] Base map source: CIA World Factbook 2010.

[10] DANTEs, Edmond - “Naval Build-up to Continue Unabated,” Asian Defense Journal, p. 52 apud CARTER, Clarence Earl - The Indian Navy: a military power at a political crossroads, p. 6.,

[11] CIA World Factbook 2010 [on-line], data refered to 2010.

[12] CIA World Factboo 2010 [on-line], data refered to 2009.

[13] Source: shipping density data adapted from National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, A Global Map of Human Impacts to Marine Ecosystems [on-line].

[14] Main sea ports are Chennai, Cochin, Ennore, Haldia, Jawaharlal Nehru, Kandla, Kolkata, Marmagoa, Mumbai, New Mangalore, Paradip, Tuticorin and Vizag (Visakhapatnam).

[15] MONTEIRO, Eugénio Viassa – O Despertar da Índia, pp. 220-221.

[16] China considers Taiwan a province (CIA World Factbook 2010).

[17] SCHAFFER, Teresita; MITRA, Pramit – India as Global Power?, p. 9.

[18] ANANDA, Alok – Rise of Chinese and Indian Navies, p. 47.

[19] This aim is stated in the “Indian Navy vision” (The Indian Navy’s Vision Document, 2006). The full spectrum of conflict commonly goes from “humanitarian operations” to the “unlimited nuclear conflict”.

[20] The benign roles include “humanitarian assistance and disaster relief”, “non-combat evacuations”, “hydrography” and “building maritime consciousness”, India’s Maritime Military Strategy 2007, pp. 95-96.

[21] SCHAFFER, Teresita; MITRA, Pramit – India as a Global Player?, p. 11.

[22] Presently it represents about 14% (2005) but until 1988 was about 40% (. India is aiming to restore the earlier participation rate of 40% (Freedom to use the seas: India’s Maritime Military Strategy, p. 43).

[23] Base map source: Wikipedia.

[24] RODRIGUES, Alexandre Reis - O Emprego do Poder Naval no Século XXI, Jornal de Defesa [on-line].

[25] The ancient “Rig Vedda” written around 2000 b.C., despite its mythological nature, refers the knowledge of ocean routes and naval expeditions to subdue other kingdoms (Singh, 1985).

[26] NAIDU, G.V. C. – Indian Navy and the Southeast Asia, p. 30.

[27] Indian Navy, 2010 [on-line].

[28] Indian Marine, also known as the “Honourable East India Company’s Marine” was formed in 5th September 1612 when a squadron of ships arrived in the roadsted off Surat (Singh, 1985). There’s a incoherence in the names (“Indian Marine” or “Royal Indian Marine”) and years (1611 or 1612) between different authors, Singh and Naidu, for example.

[29] NAIDU, G.V. C. – Indian Navy and the Southeast Asia, p. 30.

[30] NAIDU, G.V. C. – Indian Navy and the Southeast Asia, pp. 31-32.

[31] “INS” is the prefix of all navy crafts and stands for “Indian Naval Ship”.

[32] NAIDU, G.V. C. – Indian Navy and the Southeast Asia, pp. 50-60.

[33] CARTER, Clarence Earl – The Indian Navy a military power at a political crossroads, p. 11.

[34] Federation of American Scientists [on-line].

[35] The Indian’s Navy Vision Document.

[36] CARTER, Clarence Earl – The Indian Navy a military power at a political crossroads, pp. 4-6.

[37] Naval ships are ships run by the navy but not having military requirements like resilience and redundancy systems as military units normally have.

[38] Base map source: United Nations

[39] Indian Navy [on-line].

[40] INS “Viraat” is to be considered for “use in tactical battles at sea (…) to control a specific area of the sea not for strategic purpose”. Indian Navy Chief of Staff, 1987.

[41] NAIDU, G.V. C. – Indian Navy and the Southeast Asia, p. 86.

[42] This includes Destroyers, Frigates, Corvettes, Patrol Boats and Amphibious Ships.

[43] Former United States Navy USS “Trenton”

[44] The terminology conventional or nuclear submarine, is related with the propulsion system of the submarine. A nuclear submarine might not have any nuclear weaponry. At the present there are only five nations with nuclear submarines: China, France, Russia, United Kingdom and United States.

[45] From the 16 submarines, two of them are used for training purposes. Nevertheless, a fleet of 14 submarines is still significant.

[46] There has been plans since 1970s for and Indian-built nuclear submarine.

[47] PANDA, Rajaram – Arihant-Strengthening India’s Naval Capability, p. 1.

[48] There is, several controversial information, regarding the capabilities of INS “Arihant”. Nevertheless, it is a fact that India has a nuclear submarine, representing by itself a large submarine construction technology evolution and ability.

[49] See map 6 – Indian Navy establishments.

[50] Indian Navy classification.

[51] SAM-Surface to Air Missile.

[52] SSM-Surface to Surface Missile

[53] Source: Indian Navy [on-line] and WATTS, Anthony J. – Jane’s Warship Recognition Guide.

[54] “The operational readiness of the fleet is reported to be as low as 50 percent”, CARTER, Clarence Earl - The Indian Navy: a military power at a political crossroads, p. 18.

No comments:

Post a Comment