SOURCE:

http://web.stanford.edu/group/mappingmilitants/cgi-bin/groups/view/223?highlight=Tehrik-i-Taliban

http://web.stanford.edu/group/mappingmilitants/cgi-bin/groups/view/223?highlight=Tehrik-i-Taliban

Hizb-ul-Mujahideen

MAP HIZB-UL-MUJAHIDEEN

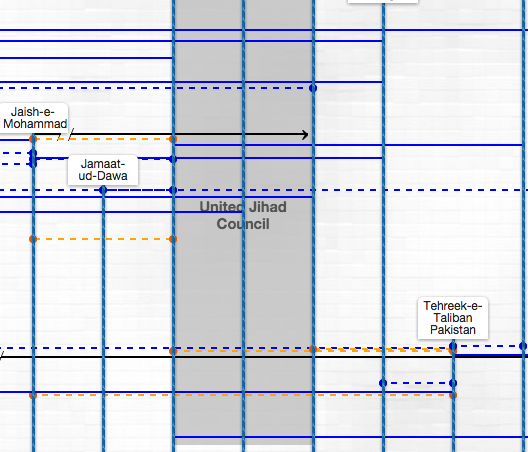

Click on the maps below to visualize this group's interactions with other militant organizations

On Pakistan -- All map

CONTENTS

- Basic Information

- Narrative Summary

- Leadership

- Ideology & Goals

- Size Estimates

- Relationships with Other Groups

SEARCH

These terms from your search are highlighted: Tehrik-i-Taliban. Clear highlighting.

Hizb-ul-Mujahideen

| Formed | 1989 |

|---|---|

| Disbanded | Group is active. |

| First Attack | January 16, 1990: HM militants attacked Jammu and Kashmir Police Constable and hanged him from a tree in Srinagar, Kashmir, India. (1 killed, 0 wounded) [1]. |

| Last Attack | November 10, 2010: HM along with Jameeat-ul-Mujahideen militants attacked and killed two Indian Central Reserve Police Force in Pattan, Kashmir, India. (2 killed, 0 wounded) [2]. |

| Updated | August 8, 2012 |

NARRATIVE SUMMARY

Hizb-ul-Mujahideen(HM) was formed in Pakistan controlled Kashmir in 1989. Pakistan's famous religious political party Jamaat-e-Islami reportedely formed HM under the influence of Pakistan's intelligence agency ISI to counter the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Fron(JKLF), an organization which had advocated complete independence of the State.

HM's organization was formalized in June 1990, when its 'Constitution' was approved and Syed Salahuddin was made the patron of the organization. But soon after, there were differences between the Jamaat-e-Islami and non Jamaat-e-Islami elements of HM which led to a split; one of the factions was led Syed Salahuddin, while the other one was led by Hilal Ahmed Mir, who was killed in 1993.

LEADERSHIP

- Muhammad “Master” Ahsan Dar (1989 to 1990): Master Ahsan Dar was the founder of Hizbul Mujahideen.[3]

- Mohammed "Syed Salahhudin" Yusef Shah (1990 to Unknown): When the HM "Constitution" was agreed upon in 1990 it named Syed Salahhudin as Patron of HM.[4]

IDEOLOGY & GOALS

- Jihadist

HM’s primary goal is to unite both Azad Kashmir (Pakistan controlled) and Jammu and Kashmir (Indian controlled) into one entity that would then join with the Pakistani state[5]. Many claim that HM was started by the ISI for the sole purpose to act as a counter to the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front, a militant organization that also fights against the Indian government, but strives to create an independent Kashmiri state[6].

SIZE ESTIMATES

According to the South Asian Terrorism Portal (SATP), HM cadres are in the range of 1500 in total.

RELATIONSHIPS WITH OTHER GROUPS

HM’s relationship with Jamaat-i-Islami is unclear, with some sources claiming HM to be the armed wing of the group, while others maintain that they are only closely linked.[9] Whatever the case may be, the two groups are connected and it appears that they do act independently on occasion, which is of great embarrassment to JI.[10] Adding to the difficulty of discerning the full extent of the relationship is the fact that both groups are intent on denying that any such relationship exists, though for observers some sort of link is obvious.

It has also been reported that HM trained alongside the Afghan Hizb-i-Islami, run by Gulbaddin Hekmatyar throughout the mid-1990’s until the Taliban gained power.[11]

HM is further part of an umbrella organization known as the United Jehad Council (UJC), which is headed by HM chief Syed Salahuddin.

· Al-Badr split from HuM in 1998 after helping to form HuM in 1989.[12]

· As of ’05 HM was part of the United Jihad Council, a collection of groups fighting in Kashmir.[13]

· Some claim that HM has been infiltrated by AQ.

· HM has reportedly carried out attacks in coordination with LeT.

REFERENCES

- ^ Global Terrorism Database Incident Summary, Incident # 199001160014. Accessed on May 3, 2012 at http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/search/IncidentSummary.aspx?gtdid=199001160014

- ^ Shabir Ibn Yusuf, “Militants kill two CRPF troopers at Pattant; high alert sounded in north Kashmir,” The Kashmir Times, November 11, 2010. Accessed from LexisNexis Academic on May 3, 2012.

- ^ “Hizb-ul-Mujahideen (HM)” GlobalSecurity.org. Accessed on May 2, 2012 at http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/para/hum.htm .

- ^ “Hizb-ul-Mujahideen (HM)” GlobalSecurity.org. Accessed on May 2, 2012 at http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/para/hum.htm .

- ^ http://www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/crt/2002/html/19992.htm

- ^ “Hizb-ul-Mujahideen (HM)” GlobalSecurity.org. Accessed on May 2, 2012 at http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/para/hum.htm

- ^ Arif Jamal, “A Guide to Militant Groups in Kashmir,” Terrorism Monitor 8 (2010). Accessed online on May 3, 2012 at http://www.jamestown.org/programs/gta/single/?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=36005&cHash=1c4ef28fa3 .

- ^ http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/countries/india/states/jandk/terrorist_outfits/hizbul_mujahideen.htm

- ^ Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Pakistan: The relationship between the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI) and Hizbul Mujahideen (HM); recent human rights violations committed by HM; whether HM practices forced recruitment in Azad Kashmir, 24 July 2003, PAK41668.E, available at:http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/3f7d4df20.html . Accessed July 9, 2012.

- ^ Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Pakistan: The relationship between the Jamaat-i-Islami (JI) and Hizbul Mujahideen (HM); recent human rights violations committed by HM; whether HM practices forced recruitment in Azad Kashmir, 24 July 2003, PAK41668.E, available at:http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/3f7d4df20.html . Accessed July 9, 2012.

- ^ http://www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/crt/2002/html/19992.htm

- ^ “Al-Badr,” GlobalSecurity.org. Accessed on May 2, 2012 athttp://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/para/Al-Badr.htm .

- ^ Bill Roggio, “Hizbul Mujahideen chief: Pakistan allows terror group to run ‘hundreds of training camps,” The Long War Journal, May 27, 2011. Accessed on may 2, 2012 athttp://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2011/05/hizbul_mujahideen_ch.php

***********************************************

CLICK / GOOGLE BELOW TO OPEN THE MAPPING OF MILITANT ORGANIZATIONSMapping Militant Organizations

mappingmilitants.stanford.edu/

Jun 6, 2012 - Mapping Militant Organizations · Stanford ... The Mapping Militants Project identifies patterns in the evolution of ... For more information or to contact us, see our About page. ... relationships between the Islamic State and global militant groups. ... The map of Pakistani militants includes those organizations ...Pakistan -- All | Mapping Militant Organizations

web.stanford.edu/group/mappingmilitants/cgi-bin/maps/view/pak

View Mode. Choose a category to bring to the front of the map. Groups ... TehreekMAP HIZB-UL-MUJAHIDEEN

Click on the maps below to visualize this group's interactions with other militant organizations

CONTENTS

- Basic Information

- Narrative Summary

- Leadership

- Ideology & Goals

- Size Estimates

- Relationships with Other Groups