SOURCE:

https://understandingempire.wordpress.com/2-0-a-brief-history-of-u-s-drones/

History of U.S. Drones

Understanding Empire

A Lightning Bug over Vietnam – one of the first drones used for surveillance by the U.S. Air Force.

The MQ-1 Predator is perhaps the most well-known of all military drones used today. It has a wingspan of 55 feet, a length of 27 feet, and can reach speeds of up to 135mph. According to the U.S. Air Force, “The Predator system was designed in response to a Department of Defense requirement to provide persistent intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance information combined with a kill capability to the warfighter.” Its deathly name conjures images of a science-fiction dystopia where robots hover in the sky and exterminate humans on the ground. Of course, this is no longer science-fiction.

Drone operators sat in a Nevada desert, huddled in air-conditioned cubicles, now control a fleet of robots that can loiter above the landscape with advanced sensing capabilities. According to The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, up to 3,800 people have been killed in 405 strikes in Pakistan, where the drones are controlled by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Dating back to 2004, the controversial program targets al-Qaeda and Taliban-linked militants, and generates fierce debate for its seeming violation of international humanitarian law and national sovereignty.

But we didn’t wake up in this brave new Droneworld overnight. Instead, there were a series of historical conditions and personalities that gave rise to this lethal atmosphere. The purpose of this essay is to review some of these key lines of descent.

Drones long history. One of the first recorded usages of drones was by Austrians on August 22, 1849. They launched some 200 pilotless balloons mounted with bombs against the city of Venice. And less than two decades later, balloons were flown in the U.S. Civil War in 1862, with both Confederate and Union forces using them for reconnaissance and bombing sorties. Fast forward over twenty years to 1898, during the Spanish-American War, and we find the U.S. military fitting a camera to a kite, producing the first ever aerial reconnaissance photos.

In World War I, aerial surveillance was used extensively. Analysts used stereoscopes to hunt for visual clues about enemy movements on photos that were stitched together to form mosaic maps. For example, the Royal Flying Corps took over 19,000 aerial photographs and collected a staggering 430,000 prints during the five months of the Battle of the Somme in 1916. This visual analysis upturned the horse as the dominant technology of military reconnaissance.

The origins of the electronic drone can be traced to the “target drones” used in the early twentieth century. These “dumb” drones were used to test and train combat pilots and anti-aircraft gunners. Indeed, the evolution of U.S. drones can be understood as the passage of three overlapping phases: the drone as a “target”, the drone as a “sensor,” and the drone as a “weapon.”

In any case, remote control would not be possible without strides in radio technology. The telegraph heralded the start of the telecommunications revolution. In 1858, the first transatlantic telegraph was completed, marking a key annihilation of space by time. The first official message on August 16th 1858 read, “Europe and America are united by telegraphic communication. Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace, goodwill to men.” The planet had suddenly become smaller. But the submarine cable was fragile and slow, and communication was bound to the physical limits of terrain and cable. Radio, however, could travel through the atmosphere. The electromagnetic spectrum offered a radical liberation for human exchange.

Nikola Tesla first demonstrated the remote control of vehicles at the end of the nineteenth century. On a pond in Madison Square Garden in 1898, the inventor and showman remotely controlled a boat with a radio signal. This was the first such application of radio waves in history, meaning that Tesla’s Patent No. 613,809 was the birthplace of modern robotics. On that body of water floated enormous, and largely unrecognized, military potential.

In 1916, and across a shrinking Atlantic, the idea of remotely guided weapons sparked the interest of Captain Archibald M. Low, of the Royal Flying Corps in the U.K. Low oversaw the construction of a number of remotely piloted planes that were fitted with explosive warheads. This included the “Aerial Target,” which was first launched in March 1917 from the rear of a truck in England. But the lightweight wooden plane–along with successive incarnations–largely failed to maintain its altitude. Crucially, however, for the period in which they were airborne, the Aerial Targets did respond to radio control, thus launching Tesla’s 1898 “teleautomaton” into the skies.

Back in the U.S., two drones were enjoying more success. In 1917, Elmer Sperry, together with inventor and radio engineer Peter Hewitt, began construction of the radio-controlled “Hewitt-Sperry Automatic Airplane” or “flying bomb.” The Automatic Airplane was able to fly 50 miles carrying a 300-pound bomb after being launched by catapult. Importantly, the pilotless plane was stabilized with the addition of Sperry’s gyroscopic technology. The success of this project led the U.S. Army to commission a second project, the rail-launched Kettering Aerial Torpedo “Bug,” developed by the Dayton-Wright Airplane Company. The Bug was essentially an aerial torpedo: pilotless and guided by preset controls. “After a predetermined length of time, a control closed an electrical circuit, which shut off the engine. Then, the wings were released, causing the Bug to plunge to earth – where its 180 pounds of explosive detonated on impact.” In Germany, a similar project was being pioneered by Dr. Wilhelm von Siemens between 1915 and 1918. The Siemens Torpedo Glider was a missile that could be dropped from a Zeppelin and then guided towards its target by radio. The flying bomb, the Bug, and the Torpedo Glider were all early forerunners to contemporary cruise missiles. But the existence of such planes remained at an experimental stage.

Throughout the 1920s, various remotely controlled ships were used for artillery target training. The late 1930s then saw a “rush of military interest in remotely controlled vehicles,” (Dickson, The Electronic Battlefield, p.181) out of which emerged the second generation “Bug,” as well as the “Bat,” a radio-controlled glide bomb used towards the end of World War II. The British-based “Queen Bee” (and later “Queen Wasp”) was also used for firing practice. In the mid-1940s the GB-1 Glide Bomb was developed to bypass German air defenses. It was a workable glider fitted with a standard 1,000 or 2,000-pound bomb. Made with plywood wings, rudders, and controlled by radio, the GB-1s were dropped from B-17s and then guided by bombardiers to their target below. In 1943, one hundred and eight GB-1s were dropped on Cologne, causing heavy damage. Later in the same war came the GB-4, or the “Robin,” which was the first “television-guided weapon.” Although potentially revolutionary, the crude image could only function in the best atmospheric conditions.

The English-located project known as Operation Aphrodite was one of the most ambitious drone projects in the Second World War. The plan was to strike concealed German laboratories with American B-17 “Flying Fortresses” and B-24 bombers that were stripped down and crammed with explosives. A manned crew would pilot these planes before parachuting out once they crossed the English Channel. At this moment, a nearby “mothership” would take control, receiving live feed from an on-board television camera. Despite the inventiveness of the U.S. Air Force and Navy, Aphrodite was a military failure. It even claimed the life of Joseph Kennedy Jr, after his B-17 exploded over the English countryside. But the military was not about to give up: the development of Aphrodite, together with the strides the Germans were making with the V1 and the more sophisticated V2 missiles, accelerated the development of U.S. unmanned projects. Set against this was the fact that around 40,000 U.S. aircraft were lost in World War II, together with 80,000 crewmembers. There was thus a financial and human drive towards a robotic air force: it was a cheaper, safer way to fight war.

In late 1946 a special “Pilotless Aircraft Branch” of the U.S. Air Force was established to develop three types of drones for use as training targets. Of the three, the airborne-launched Q-2 was the most important, becoming the “father” of a class of target drones built by the Ryan Aeronautical Company. The “Firebees” were first tested in 1951 at Holloman Air Force base. The early Firebee could stay in flight for two hours and was capable of reaching heights of up to 60,000 feet. In 1960, Gary Powers was shot down over the Soviet Union while piloting a U-2 spy plane. The Eisenhower administration scrambled to replace its manned reconnaissance program. In 1960, Ryan Aeronautical Company (since acquired by Teledyne Inc.) proposed a version of its target drone called Red Wagon as a reconnaissance vehicle. In 1962, Ryan was given money from the Air Force’s “Big Safari” funds and built its first surveillance drone. The jet-powered Firebees went by several military designations: “Ryan 147,” “AQM-34,” and “Lightning Bug.” They were launched from the wings of a Lockheed DC-130 Hercules airplane, which acted as a coordinating mothership for its swarm of drones. The Lightning Bugs flew pre-programmed routes and could also be controlled by Airborne Remote Control Officers onboard the Hercules. After performing their surveillance mission the Lightening Bugs deployed their parachutes and were scooped up by helicopters under the guidance of “Drone Recovery Officers.”

In May of 1964, the U.S. first began to consider sending drones to replace its U-2s in spying missions over Cuba. Lightning Bugs flown by U.S. Strategic Air Command were subsequently used for surveillance in so-called “denied areas” across an increasingly widening Cold War battlespace: including Cuba, North Korea, and the People’s Republic of China. In November 1964, The Washington Daily News reported that, “Communist China claimed to have shot down a U.S. reconnaissance plane with no pilot.” Time also reported that, “Communist China held an official ceremony celebrating a “major victory” in the shooting down of ‘a pilotless, high-altitude reconnaissance military plane of U.S. imperialism’ over Central-South China.” The U.S. military remained quiet about the wreckage from the secret project: much like it would decades later after the Iranians captured an advanced CIA drone.

Lightning Bugs were widely used over North Vietnam after Rolling Thunder officially ended in 1968. The “electronic battlefield” of the Vietnam War is pivotal to understanding the development of contemporary drone warfare. It marked the turning point in which drones morphed from being “targets” to remote “sensor” platforms that could survey the landscape below. According to Col. John Dale, who was director for Strategic Air Command’s 15th Air Force headquarters, the Lightning Bugs continually confounded MiG fighters over China, North Korea, and Vietnam, by flying at very low altitudes. As Dale stated, “from October 1968 to November 1972 – four years – we were the only aircraft flying in North Vietnam,” adding that thanks to CIA support, “we were able to do so much for so long, because there weren’t any politicians involved.”

The robotic eyes in the sky were successful. “In Vietnam, the 147 drones [Lightning Bugs] were used so extensively and for such a variety of missions that Southeast Asia operations jocularly are referred to as the “Tonkin Gulf Test Range.” Between 1964 and 1975, more than 1,000 Lightning Bugs flew over 34,000 surveillance missions across Southeast Asia. Indeed, “Often unknown to both those who looked at them and those that published them, many of the aerial views of North Vietnam that appeared in the American press were taken by the drones” (Dickson, p.188). South of the seventeenth parallel, drones were being trialed as “electronic listening devices” in Igloo White. This included the QU-22B Beech aircraft (Pave Eagle), a prototype unmanned system that was ultimately beset by too many teething problems. But the war managers were not about to give up: thousands of U.S. airmen had died, and thousands of planes had been destroyed. As the Vietnam War was winding down, the robots were gearing up.

The drone revolution was kickstarted by a May 1970 symposium sponsored by the Air Force and the RAND Corporation. After the second symposium in July, it was decided that the time was ripe for remotely piloted vehicles (RPVs). The Air Force launched the Compass Cope program in the 1970s to increase the range and electronic surveillance capabilities of RPVs. The program involved funding Boeing and Ryan to develop high-altitude, long-endurance drones. These prototypes were the most ambitious unmanned surveillance drones in Air Force history, capable of flying for over 24 hours and piloted from the ground. At the same time that drones were getting bigger– more like the U-2s they were replacing–a range of “mini-RPVs” were developed. An example would be the Praeire prototypes, which were capable of carrying laser designators and TV cameras. In addition to surveillance drones, the Air Force began experimenting with weaponized Firebees. In May of 1973, the Philco-Ford Corporation developed a laser designator that could be attached to a Ryan BGM-34B Firebee drone, with the aim of creating a “strike drone.”

The 1970s were defined by a mixture of unease, skepticism, speculation, and outright hyperbole about the end of the human pilot. Some of the unease stemmed from the day a human pilot was “defeated” by a drone. In 1971, a Ryan official challenged John Smith, then commander of the Navy Fighter Weapons “Top Gun” School to fly against a drone. The F-4 Phantom and its pilot could not keep pace with the inhuman twists and turns the robot was pulling.C ontrolled by pilots on the ground, the Firebee managed to score several “hits” on the F-4 The 1980s saw the robotic torch pass to Israel. It used Pioneer drones in the early 1980s against Syrian forces, leading to the formation of the joint Pioneer UAV Corporation (uniting Israel Aircraft Industries with the AAI Corporation). Nearly all the pieces were in place for the Predator Empire. Except, of course, the Predator. It would take decades before the next phase: the drone as weapon.

In the next section, I want to explore this phase, tracing the historical rise of the Predator drone, beginning in the 1980s. In particular, I want to explore how the American drone became an object of power in tandem with a series of legal objects. While advancements in drones were driven by the requirements of cartographic intelligence, these unmanned objects were very much bound to a series of legal objects that enabled their deployment. In other words, the relationship between technology and law is extremely important in charting the rise of the Predator drone: both come together in the production of geographic knowledge and surveillance, target acquisition, and wider economies of life and death. This relationship between technology and law is embodied in two contrasting figures that did more than most to fuel the motors of the Predator Empire: An Israeli engineer called Abraham Karem and a Saudi jihadist called Osama bin Laden.

Abraham Karem was born in Baghdad, the son of a Jewish merchant. His family moved to Israel in 1951, and by the 1970s, the young Karem was already building aircraft for the Israeli Air Force, during which time aviation engineers were attempting to satisfy the need for real-time intelligence. In 1980 he emigrated from Israel to Los Angeles and started to build aircraft in his garage. A year later he wheeled out a bizarre, cigar-looking aircraft called the ‘Albatross’ that would change the face of warfare forever.

At Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, Karem demonstrated that his Albatross could stay in the air for 56 hours straight. This was somewhat of a revelation. During the Vietnam War, U.S. drones were programmed to fly a pre-programmed route and take still-photographs. But they could only stay in the air for around two hours. The flight of the Albatross led to funding from DARPA, the military’s research and development department. The first outcome from this seed money was a drone called the Amber, developed by Karem’s company Leading Systems Incorporated. Although the Amber enjoyed much success, including demonstrating a flight endurance of 40 hours by 1988, it soon became apparent that the Amber was insufficient for prolonged surveillance: it was unable to carry large quantities of fuel or sophisticated sensor equipment. Leading Systems responded to this deficiency by rolling out the GNAT-750 in 1989. The GNAT improved on the Amber in a number of ways: it was equipped with GPS navigation, which allowed for autonomous missions of up to 48 hours, and also housed infrared and low-light cameras in a moveable sensor turret under its nose.

Karem’s company found itself in fiscal trouble when the military decided not to pursue large-scale development of the Amber. The U.S. Congress had become impatient with UAV development, and by 1990, the Pentagon was forced to consolidate its UAV research into a single Joint Program Office, which wasn’t budgeted for any research. Congress also banned DARPA from supporting UAV projects outside of the jurisdiction of the Pentagon’s JPO, which effectively killed off UAV development, including the embryonic Amber and GNAT programs. Financially stretched, Karem sold his company to Hughes Aircraft, which in turn sold it to San Diego-based General Atomics in 1990. General Atomics decided to continue development of the GNAT-750, and Karem was made part of the company’s subsidiary called General Atomics Aeronautical Systems.

In 1993, three years after General Atomics assimilated Karem’s team, the Pentagon issued a requirement to support UN peacekeeping forces in the former Yugoslavia. What is often referred to as the Bosnian war took place between 1992 and 1995, and resulted in around 100,000 people killed, tens of thousands of women raped, and millions more displaced. In the serenity of the skies however, the GNAT-750 was flown to provide overhead surveillance for NATO convoys and for spotting Serbian artillery.

Because of the urgent need for surveillance as the war unfolded, existing, cumbersome, military acquisition procedures were controversially skipped over. The CIA was able to circumvent the Congressional block on UAV development because it operated outside of military jurisdiction. To recall, drone development in the military been effectively halted through the Congressional JPO. And this presented the perfect opportunity for the CIA. By 1993 the agency had become frustrated with poor quality satellite intelligence over Bosnia. Woolsey, then director of the CIA, was already acquainted with Karem, and looked to General Atomics for a plane that could provide a persistent aerial presence and real-time surveillance. Under the codename LOFTY VIEW, the CIA would operate the GNAT-750 in total secrecy. The GNAT first flew over Bosnia in February of 1994 from nearby Albania (according to Mark Mazzetti – the hangar was rented in exchange for two trucloads of wool blankets, and money came from Representative Charlie Wilson). According to the CIA director, “I could sit in my office, call up a classified channel and in an early version of e-mail type messages to a guy in Albania asking him to zoom in on things”.

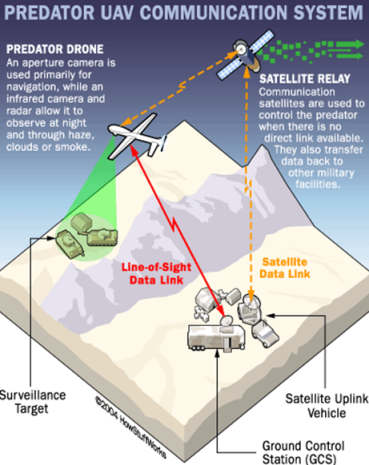

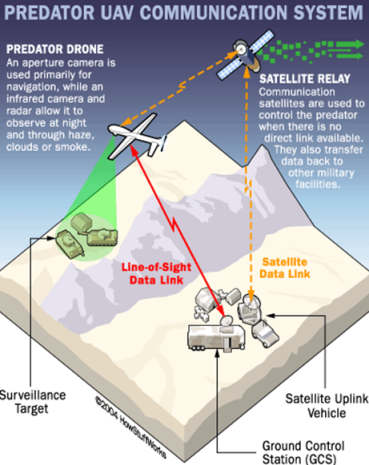

But codename LOFTY VIEW was not a real success. The GNAT was vulnerable to inclement weather. And the biggest impediment was the communication device housed in the aircraft’s fuselage: the C-band line-of-sight data link only had a range of around 150 nautical miles. This meant that the drone could only be controlled from a relatively close proximity; seriously restrict its surveillance capabilities. The CIA initially tried to overcome this by using an intermediary aircraft to relay the data, thereby extending the flight orbit of the GNAT. But this relay did not solve the GNAT’s data problems. The surveillance imagery produced simply had too far to travel: from a GNAT-750, to a relay aircraft, to a ground station in Albania, to a satellite circulating the planet, and then finally, onwards to the CIA headquarters in Langley.

Atomics responded with the Predator. The Predator drone extended the GNAT’s limited range with the addition of a Ku-band SATCOM data ink. The new satellite communications overcame the limited data link of the GNAT and the limitations of the C-band line-of-sight. In fact, a SATCOM link meant that American drone operators didn’t even have to be in same region or even continent as the drone. The Predator drones were first flown in June 1994, and were deployed to the Balkans under Operation Nomad Vigil and Operation Deliberate Force in 1995, the latter the name for the NATO air campaign against Bosnian Serb forces. Both the GNAT-750 and its offspring the Predator served simultaneously due the massive demand placed on surveillance aircraft. Future developments of the Predator included a de-icing system, reinforced wings, and a laser-guided targeting system: the latter two improvements were essential for weaponising the drone in its later life.

In 1995 Predators were shown in an aviation demonstration at Fort Bliss. Impressed by the drone’s capabilities, the U.S. Air Force soon established its very first UAV squadron, the 11th Reconnaissance Squadron at Indian Springs Auxiliary Airfield in Nevada, later named as Creech Air Force Base in 2005. Creech remains the current hub of American drone operations in Afghanistan.

After the CIA’s Predator drone spotted who it believed was bin Laden at Tarnak Farm, Afghanistan, in 2000 (more on this below), research went into shortening the kill-chain: getting Tomahawk missiles to fly from a submarine in the Arabian Sea to southern Afghanistan would take six hours to go through military protocols. The Predator’s Hellfire was the solution. At Indian Springs, Nevada, a program was born under the Air Force’s “Big Safari” office, a classified division in charge of developing secret intelligence programs for the military. In 2001 tests were made early in the year to turn the hunter into a killer.

In sum, what started in Abraham Karem’s Los Angeles garage as a funny-looking Albatross had become a Predator drone with global ambitions. And war would never quite be the same. But this is only half of the story.

A Tall Man in Robes

Osama bin Laden moved from Saudi Arabia to Peshawar, Pakistan in or around July of 1986. He was a well-known figure among Muslim Brotherhood-connected rebels, and helped finance the Afghan mujahideen, opening his first training facility in the same year.

By this time, the CIA had also funnelled millions of dollars to Afghan jihadists for half a decade (see Coll, 2004). Under Ronald Reagan’s Cold War warriors, the CIA had directly and indirectly aggrandized violent figures such as Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Jalaluddin Haqqani. The latter figure, a respected Pashtun commander, had full CIA support, and his organization—the Taliban-linked Haqqani network—would later re-emerge as a terrorist organization and drone target in the ‘war on terror’.

By the early 1990s, bin Laden was certainly on the CIA’s radar, but Afghanistan, increasingly, was not. As the Cold War thawed, counter-terrorist activity and human intelligence in the region faded, leaving a massive blind-spot in the agency’s knowledge. When President Clinton signed Executive Order 12947 in 1995, which imposed sanctions against 12 terrorist groups around the world, neither al-Qaeda nor bin Laden made the list.

There was one exception to this intelligence malaise: the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center (CTC). The CTC was established in 1986, under the Directorate of Operations, and was designed to unify the disparate regional intelligence knowledges of the CIA’s station bureaus. In recognition of bin Laden’s growing importance to global terrorist operations, in January 1996 the CTC opened a new ‘desk’ solely to track him down. By this time, bin Laden had ingratiated himself with the Afghan Taliban, whose brutal regime ruled Kabul between 1996 and 2001. On February 23, 1998, bin Laden—previously known to the CIA as a financier rather than strategist—unveiled a key fatwa from his organization, the World Islamic front, called “The International Islamic Front for Jihad Against Jews and Crusaders”. The CIA viewed bin Laden’s escalating rhetoric, which called for the indiscriminate killing of Americans and Jews, with deep concern. After two American embassies in Africa were bombed in 1998, Clinton announced that bin Laden had launched a ‘terrorist war’ against the U.S. In retaliation to these bombings in Tanzania and Kenya, the American President approved the launch of seventy-five tomahawk missiles at Afghanistan. The missiles missed bin Laden, but did kill twenty or so militants. The hunt was still on.

During this time, the legality of bin Laden’s assassination was a constant discussion point. The CIA’s official legal authority to conduct covert operations stems from the powerful precedent of Executive Order 12333, signed by President Ronald Reagan in 1981, to “Conduct counterintelligence activities outside the United States” (1.8.C). However, the same act (2.11) states that “No person employed by or acting on behalf of the United States Government shall engage in, or conspire to engage in, assassination”. This long-standing ban on U.S. assassinations was relaxed by President Clinton in a 1998 Presidential Finding (or Memorandum of Notification) that allowed some lethal force against bin Laden and his lieutenants in Afghanistan. There remains confusion as to the actual wording and prescription of this Presidential finding due to the legal and bureaucratic debate surrounding whether or not bin Laden’s assassination was in violation of international law. By early 1999, George Tenet, director of the CIA, had become increasingly frustrated by the lack of attention given to the growing threat of al-Qaeda in Clinton’s cabinet. By now the CTC estimated that al-Qaeda was operating in 60 countries. Tenet had a plan to hunt bin Laden down, which came to be known as The Plan. He named Cofer Black as head of the CTC, and sought to focus CIA resources on al-Qaeda. His hire symbolized a more ‘kinetic’ of ‘paramilitary’ response to bin Laden. The gloves were coming off.

A Missed Opportunity

The CIA did have a history with drones prior to the Predator. In the first years of the agency’s CTC, its founding director, Dewey Clarridge, had sought drones to help search for American hostages in restricted areas of Beirut and Lebanon. Clarridge had also experimented with arming the drones with small rockets, but they were too inaccurate for their purpose. When the Air Force began demanding fast, jet-like drones in the 1990s, the CIA wasn’t interested: they preferred smaller drones that could take pictures in situations where satellites or spy planes could not. When the CIA secretly embraced the Predator drone in 1993, many in the Air Force were unhappy. But ultimately, the CIA arranged for Air Force teams trained by the Eleventh Reconnaissance Squadron at Nellis Air Force base to operate the agency’s clandestine drones. The Predator’s ability to hover above a target for hours, relaying high-resolution live surveillance, was invaluable.

Not everyone in the CIA was sold. Some saw the Predator as a technological fix that undermined the value of human-intelligence. As these bureaucratic debates raged on in the summer of 2000, Cofer Black, head of the CTC, was determined to weaponize the drone with an air-to-ground missile called a Hellfire. That very same summer, Uzbekistan agreed to allow Predator flights over Afghanistan from one of its own air bases. Despite the secrecy of this deal, the Uzbek government and the CIA were both extremely nervous that the control stations and vans used by CIA flight operators would attract unwanted attention. To address this problem, the Predator’s extended SATCOM data link enabled it to be controlled remotely from outside of Uzbekistan. Clinton agreed with this long-range solution, approving a limited ‘proof of concept mission’. This involved the bin Laden unit drawing up plans for 15 Predator flights, each lasting for just over twenty four hours, during which the drones surveyed bin Laden’s known haunts in Southern and Eastern Afghanistan. They wouldn’t have to wait long.

While loitering over Tarnak Farm near Kandahar on September 7th, 2000, the Predator photographed what appeared to be bin Laden: a tall man dressed in Arab robes surrounded by a ring of armed bodyguards. Almost a year before the 9/11 attacks, the Predator had captured what the agency strongly believed to be the al-Qaeda leader. But at this time, the Predator was just a surveillance plane. And as winter fell in December, winds gathered in North Afghanistan and the Predator’s small engine struggled to fight the headwind gusts, which forced the drone to keep drifting back towards Uzbekistan. The CTC had no choice but to halt the operation. During this hiatus, Cofer Black hoped that lawyers would allow the CIA to fix missiles to the Predators. After years of searching, they had probably located bin Laden at Tarnak Farm, but were unable to take the shot. And yet, Tarnak Farm inside of Afghanistan was a complicated legal and ethical target. Clinton’s administration still had not labelled the Taliban a terrorist organization, and other government officials worried about the geopolitical fallout from striking a target that housed civilians—estimated to include perhaps one hundred women and children. For now at least, the Predator remain leashed.

In February 2001, under a newly elected Bush Administration, the U.S. State department’s lawyers waived concerns that an armed drone might violate the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. This legislation was signed in 1987 by Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, and prevented ground launched ballistic and cruise missiles. As well as rubber stamping the Predator program, Hellfire missiles tests were successfully completed in exercises conducted in May and June. But the Bush administration wasn’t completely sold on drones or on Afghanistan, despite lobbying by the CIA.

By now of course, the armed Predator was virtually a CIA invention: a technology that perfectly embodied the agency’s desire to survey in secret from high in the sky. And yet, even by July 2001, the U.S. went on record to denounce Israel’s use of targeted killings. The U.S. ambassador to Israel said: “The United States government is very clearly on record as against targeted assassinations.… They are extrajudicial killings and we do not support that.”

Hellfire

“Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S.” was the headline written across President Bush’s Daily Brief as it was presented to him at his Texas ranch on the 6th of August. 9 days later, Cofer Black said “We are going to be struck soon” at the Pentagon’s classified annual conference. “Many Americans are going to die, and it could be in the U.S.” On September 4, 2001, in an important cabinet meeting, the director of the CIA presented the agency’s plan to operate the Predator drone – a lethal operation usually entrusted to the U.S. Air Force. In early September, Condoleezza Rice agreed with the CIA that an armed Predator was needed, but for now the agency should only pursue reconnaissance Predator flights in Afghanistan.

This changed just a week later. The armed Predator program was activated days after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, with Predators reaching Afghanistan by September 16th 2001, and armed Predators reaching the country on October 7th.

After 9/11 the CIA was authorized to take the “gloves off”, in the infamous words of Cofer Black. President Bush signed a directive that created a secret list of High Value Targets (HVTs) that the CIA was authorized to kill without further Presidential approval. The same broad-brush finding also enabled “disappearances” and the infamous network of global prisons and extraordinary rendition. John Rizzo, the former acting General Counsel of the CIA, authorized the finding. He said it allowed activities that were “unprecedented in my 25 years of experience at CIA” (quoted in PBS, 2011). The retired legal chief added, “Frankly, the finding was so aggressive and comprehensive that honestly there wasn’t much more that could have been added.”

The first ever CIA drone attack was a disaster. The baptismal strike occurred on the 4th of February 2002. The agency’s Predator unleashed a Hellfire missile at a “tall man” and his lieutenants near the city of Khost, believing the man to be none other than bin Laden. But the analysts had acquired the wrong target. This time, it was innocent civilians gathering up scrap metal. All were killed. Perhaps in a mark of supreme irony that defines the drone wars more generally, the site of the strike was Zhawar Kili, a mujahideen complex built by Haqqani in the 1980s with CIA support. A further irony is just how short the drones were initially deployed in Afghanistan after years of lobbying. By April 2002, American focus had already switched to the mounting invasion of Iraq. Even if the Predators had left the country, the precedent was set: the Afghan Predator program was to become the model for far deadlier CIA activity in Pakistan.

On November 4, 2002, there was the first CIA targeted killing outside of a declared war zone using the “sweeping authority” given to the spy agency by Bush in September 2001. The target was Al-Harethi, mastermind of the USS Cole bombing. Yemeni President Saleh was an “easy sell” for drone strikes: after al-Harethi was killed, the the Yemeni government claimed responsibility. But later in 2002 it leaked that the US was behind it Saleh was furious and banned drones, which wouldn’t re-emerge in the country until 2010 with Yemen in turmoil. By then Saleh was in no position to object.

Richard Clarke, who served in both Clinton and Bush administrations as the top White House counterterrorism official, conducted a review of spying operations in Afghanistan, consulting longtime CIA analyst Allen. Unlike agency director George Tenet and head of Operations Pavitt, Allen was a fierce Predator advocate. Allen was told about secret Air Force tests in the desert: there was a chance, according to Pentagon officials, that the CIA could find bin Laden using a drone. Allen brought the Predator idea back to Richard Clarke. Figuring that Tenet and Pavitt would be against the idea, they went straight to the White House, inviting advocates Black, Allen, and Richard Blee, (head of the CTC’s bin Laden hunting unit – code name Alec Station).

Pavitt said the CIA should not be operating its own Air Force. Clarke’s response to Allen “if the Predator gets show down, the pilot goes home and fucks his wife, it’s OK. There’s no POW issue here”. But by June 2000, Clarke had won the argument, and the White House had approved moving Predators to the Karshi-Khanabad Air Base in Uzbekistan. Air Force engineers bounced signal off a satellite and relayed the feed through a ground station in Germany. Spying flights began in September 2000. For Clarke, driving out to Langley to watch the video beamed into the trailer in the parking lot was surreal: “It was just science fiction; it was unbelievable” (Mazzetti, p. 93).

But even after successful tests the CIA was divided. Pavitt was against it – he wanted more case officers rather than drones. And would the CIA or Pentagon fund it? Tenet was ambivalent at first – saying he thought it was the military, not the CIA, that should pull the trigger. And the CIA was also worried about future blowback – what if an administration down the line ruled the Predator program to be illegal? 9/11 ended these worries.

Pakistan

Since 2004 the CIA has been conducting aerial surveillance and targeted killings across Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas. But why 2004? It all centers around an important Pashtun figure: military commander Nek Muhammad. He was a “second generation” mujahedeen warrior who saw no necessary loyalty to Pakistan’s ISI, who had aided his predecessors in the Afghan mujahdeen of the 1980s. Muhammad first fought in 1993 with the Afghan Taliban against the Northern Alliance. He later hosted fleeing Arab and Chechen fighters that moved into Pakistan in 2001 and 2002.

Under pressure from George Bush and the CIA’s shadowy “global war on terror”, the Pakistan military invaded South Waziristan in March 2004. The local tribesmen were furious, and attacks against Frontier Corps posts increased. Islamabad soon looked for a way out, and signed a peace deal with Muhammad in 2004, only a month after combat operations had begun. This was a “deal” that greatly expanded Muhammad’s power, and would ultimately lead to the formation of the Pakistani Taliban or TTP. But he soon reneged on his promise, attacking Pakistani soldiers. Islamabad was furious.

And so it granted the CIA airspace for drone strikes. But there was one condition: Muhammad would be the first target. Moreover, the ISI insisted that they approve each and every strike, giving them control over the kill list, and small “flight boxes”. Partly this was because Islamabad didn’t want American drones poking their nose over its nuclear facilities or Kashmiri militant groups that were being trained for attacks against India. Muhammad was killed on June 18, 2004 and CIA and ISI officials agreed Pakistan would take credit.

“After the killing of Nek Muhammad in Pakistan…the CIA began to see its future: not as the long-term jailers of America’s enemies but as a military organization that could erase them”. (Mazzetti, 2013, p. 121).

The CIA’s drone strikes are aimed at a number of militant factions in Pakistan. According to The New America Foundation the single biggest target has been the Taliban, followed by al-Qaeda and the Haqqani network—the latter, of course, is headed by the same family the CIA supported some decades earlier. According to the Conflict Monitoring Center, in 2011 alone the CIA fired 242 Hellfire missiles in Pakistan, and at a cost of $68,000, it meant the agency spent at least $16.5 million to kill 609 people. Even after President Obama’s 2012 admission that he was keeping the drone strikes “on a very tight leash”, U.S. officials do not routinely comment on the CIA’s program. Most drone strikes have taken place since U.S. President Barack Obama came to power in 2009, with the most prolific year of strikes taking place in 2010. This increase is partly a result of changes in the way targets are identified. Since 2008 the CIA began rolling out “signature strikes” against targets outside of named kill lists. In 2008, former CIA Director Michael Hayden lobbied Bush to relax drone targeting constraints further in Pakistan. No longer was a named target on a kill-list a legal prerequisite to attack. Instead, the CIA could now target individuals based on their ‘pattern of life’ or their suspicious daily behaviour. These ‘signature strikes’ use the same legal justification as the Presidential finding signed by Bush immediately after 9/11, and then re-signed by Obama in 2009, and they represent the apex of modern biopower and surveillance, honed and developed over decades.

Conclusions

The development of the drone program was not simply a technological operation; it was a bureaucratic process that required a series of legal objects to enable the Predator’s rise.

Today, the CTC still produces a list of targets that are reviewed and signed by the CIA’s general counsel. Multiple lawyers inhabit the seventh floor—the “power floor”—adjacent to the Director’s office. These lawyers produce a “five-page dossier” that covers the justification for an individual to be targeted. This shuffle of pens and papers, of files and folders, reminds us that the CIA is not a military organization; it is a civilian intelligence agency. Part of the power the CIA wields is a result of the permanent state of secrecy it exists within. Secrecy is a bureaucratic weapon institutionalized in the CIA, and a way of conducting war by other means. In effect, the CIA is an extremely adept civilian bureaucracy that shields itself from outside criticism, law, and public debate, in a way the U.S. military is unable to do. For the ACLU, the transformation is stark: “We’re seeing the CIA turn into more of a paramilitary organization without the oversight and accountability that we traditionally expect of the military.” Today, the CIA oversees a program of extrajudicial killings and geographic surveillance across the planet: in Pakistan, in Somalia, in Yemen, in Libya, in Iran, and beyond. Its global reach shows no sign of shrinking.

The Rise of the Predator Empire is a story about people; about the engineering prowess of an Israeli engineer and the determination of an exiled Saudi national. But it’s also a story about objects: about the technological capacities of the Amber, the GNAT, and finally the Predator drone: from the type of satellite data link used, to the sensing prowess of the camera, to the strength of the plane’s wings. It’s a story about legal objects called Presidential Findings that granted the CIA the ability to pursue its aggressive program in Afghanistan and then Pakistan. It’s the story of how a technology came to embody a kind of secrecy; materializing a set of social relations and bureaucratic powers.

But above all, it’s a story about geography—about the coming-together and assembling of all these objects in a distinctive time and space, from Vietnamese jungles to Pakistani mountains. And it’s a story that is far from over, as the people still living under the hum and buzz of Predators know only too well.

***

Please cite this article as: Ian G. R. Shaw, (2014), “The Rise of the Predator Empire: Tracing the History of U.S. Drones”, Understanding Empire,

https://understandingempire.wordpress.com/2-0-a-brief-history-of-u-s-drones/

References not linked in main text

Steve Coll. 2004. Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001. London: Penguin Books.

Paul Dickson, 2012. The Electronic Battlefield. Takoma Park: FoxAcre Press.

Mark Mazzetti. 2013, The Way of the Knife: The CIA, a Secret Army, and a War at the Ends of the Earth.

Ian Shaw and Majed Akhter, 2012. The Unbearable Humanness of Drone Warfare in FATA, Pakistan. Antipode 44(4), 1490-1509.

https://understandingempire.wordpress.com/2-0-a-brief-history-of-u-s-drones/

History of U.S. Drones

Understanding Empire

The State of Our Unmanned Planet

The Rise of the Predator Empire: Tracing the History of U.S. Drones

A Lightning Bug over Vietnam – one of the first drones used for surveillance by the U.S. Air Force.

The MQ-1 Predator is perhaps the most well-known of all military drones used today. It has a wingspan of 55 feet, a length of 27 feet, and can reach speeds of up to 135mph. According to the U.S. Air Force, “The Predator system was designed in response to a Department of Defense requirement to provide persistent intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance information combined with a kill capability to the warfighter.” Its deathly name conjures images of a science-fiction dystopia where robots hover in the sky and exterminate humans on the ground. Of course, this is no longer science-fiction.

Drone operators sat in a Nevada desert, huddled in air-conditioned cubicles, now control a fleet of robots that can loiter above the landscape with advanced sensing capabilities. According to The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, up to 3,800 people have been killed in 405 strikes in Pakistan, where the drones are controlled by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Dating back to 2004, the controversial program targets al-Qaeda and Taliban-linked militants, and generates fierce debate for its seeming violation of international humanitarian law and national sovereignty.

But we didn’t wake up in this brave new Droneworld overnight. Instead, there were a series of historical conditions and personalities that gave rise to this lethal atmosphere. The purpose of this essay is to review some of these key lines of descent.

Drones long history. One of the first recorded usages of drones was by Austrians on August 22, 1849. They launched some 200 pilotless balloons mounted with bombs against the city of Venice. And less than two decades later, balloons were flown in the U.S. Civil War in 1862, with both Confederate and Union forces using them for reconnaissance and bombing sorties. Fast forward over twenty years to 1898, during the Spanish-American War, and we find the U.S. military fitting a camera to a kite, producing the first ever aerial reconnaissance photos.

In World War I, aerial surveillance was used extensively. Analysts used stereoscopes to hunt for visual clues about enemy movements on photos that were stitched together to form mosaic maps. For example, the Royal Flying Corps took over 19,000 aerial photographs and collected a staggering 430,000 prints during the five months of the Battle of the Somme in 1916. This visual analysis upturned the horse as the dominant technology of military reconnaissance.

The origins of the electronic drone can be traced to the “target drones” used in the early twentieth century. These “dumb” drones were used to test and train combat pilots and anti-aircraft gunners. Indeed, the evolution of U.S. drones can be understood as the passage of three overlapping phases: the drone as a “target”, the drone as a “sensor,” and the drone as a “weapon.”

In any case, remote control would not be possible without strides in radio technology. The telegraph heralded the start of the telecommunications revolution. In 1858, the first transatlantic telegraph was completed, marking a key annihilation of space by time. The first official message on August 16th 1858 read, “Europe and America are united by telegraphic communication. Glory to God in the highest, on earth peace, goodwill to men.” The planet had suddenly become smaller. But the submarine cable was fragile and slow, and communication was bound to the physical limits of terrain and cable. Radio, however, could travel through the atmosphere. The electromagnetic spectrum offered a radical liberation for human exchange.

Nikola Tesla first demonstrated the remote control of vehicles at the end of the nineteenth century. On a pond in Madison Square Garden in 1898, the inventor and showman remotely controlled a boat with a radio signal. This was the first such application of radio waves in history, meaning that Tesla’s Patent No. 613,809 was the birthplace of modern robotics. On that body of water floated enormous, and largely unrecognized, military potential.

In 1916, and across a shrinking Atlantic, the idea of remotely guided weapons sparked the interest of Captain Archibald M. Low, of the Royal Flying Corps in the U.K. Low oversaw the construction of a number of remotely piloted planes that were fitted with explosive warheads. This included the “Aerial Target,” which was first launched in March 1917 from the rear of a truck in England. But the lightweight wooden plane–along with successive incarnations–largely failed to maintain its altitude. Crucially, however, for the period in which they were airborne, the Aerial Targets did respond to radio control, thus launching Tesla’s 1898 “teleautomaton” into the skies.

Back in the U.S., two drones were enjoying more success. In 1917, Elmer Sperry, together with inventor and radio engineer Peter Hewitt, began construction of the radio-controlled “Hewitt-Sperry Automatic Airplane” or “flying bomb.” The Automatic Airplane was able to fly 50 miles carrying a 300-pound bomb after being launched by catapult. Importantly, the pilotless plane was stabilized with the addition of Sperry’s gyroscopic technology. The success of this project led the U.S. Army to commission a second project, the rail-launched Kettering Aerial Torpedo “Bug,” developed by the Dayton-Wright Airplane Company. The Bug was essentially an aerial torpedo: pilotless and guided by preset controls. “After a predetermined length of time, a control closed an electrical circuit, which shut off the engine. Then, the wings were released, causing the Bug to plunge to earth – where its 180 pounds of explosive detonated on impact.” In Germany, a similar project was being pioneered by Dr. Wilhelm von Siemens between 1915 and 1918. The Siemens Torpedo Glider was a missile that could be dropped from a Zeppelin and then guided towards its target by radio. The flying bomb, the Bug, and the Torpedo Glider were all early forerunners to contemporary cruise missiles. But the existence of such planes remained at an experimental stage.

Throughout the 1920s, various remotely controlled ships were used for artillery target training. The late 1930s then saw a “rush of military interest in remotely controlled vehicles,” (Dickson, The Electronic Battlefield, p.181) out of which emerged the second generation “Bug,” as well as the “Bat,” a radio-controlled glide bomb used towards the end of World War II. The British-based “Queen Bee” (and later “Queen Wasp”) was also used for firing practice. In the mid-1940s the GB-1 Glide Bomb was developed to bypass German air defenses. It was a workable glider fitted with a standard 1,000 or 2,000-pound bomb. Made with plywood wings, rudders, and controlled by radio, the GB-1s were dropped from B-17s and then guided by bombardiers to their target below. In 1943, one hundred and eight GB-1s were dropped on Cologne, causing heavy damage. Later in the same war came the GB-4, or the “Robin,” which was the first “television-guided weapon.” Although potentially revolutionary, the crude image could only function in the best atmospheric conditions.

The English-located project known as Operation Aphrodite was one of the most ambitious drone projects in the Second World War. The plan was to strike concealed German laboratories with American B-17 “Flying Fortresses” and B-24 bombers that were stripped down and crammed with explosives. A manned crew would pilot these planes before parachuting out once they crossed the English Channel. At this moment, a nearby “mothership” would take control, receiving live feed from an on-board television camera. Despite the inventiveness of the U.S. Air Force and Navy, Aphrodite was a military failure. It even claimed the life of Joseph Kennedy Jr, after his B-17 exploded over the English countryside. But the military was not about to give up: the development of Aphrodite, together with the strides the Germans were making with the V1 and the more sophisticated V2 missiles, accelerated the development of U.S. unmanned projects. Set against this was the fact that around 40,000 U.S. aircraft were lost in World War II, together with 80,000 crewmembers. There was thus a financial and human drive towards a robotic air force: it was a cheaper, safer way to fight war.

In late 1946 a special “Pilotless Aircraft Branch” of the U.S. Air Force was established to develop three types of drones for use as training targets. Of the three, the airborne-launched Q-2 was the most important, becoming the “father” of a class of target drones built by the Ryan Aeronautical Company. The “Firebees” were first tested in 1951 at Holloman Air Force base. The early Firebee could stay in flight for two hours and was capable of reaching heights of up to 60,000 feet. In 1960, Gary Powers was shot down over the Soviet Union while piloting a U-2 spy plane. The Eisenhower administration scrambled to replace its manned reconnaissance program. In 1960, Ryan Aeronautical Company (since acquired by Teledyne Inc.) proposed a version of its target drone called Red Wagon as a reconnaissance vehicle. In 1962, Ryan was given money from the Air Force’s “Big Safari” funds and built its first surveillance drone. The jet-powered Firebees went by several military designations: “Ryan 147,” “AQM-34,” and “Lightning Bug.” They were launched from the wings of a Lockheed DC-130 Hercules airplane, which acted as a coordinating mothership for its swarm of drones. The Lightning Bugs flew pre-programmed routes and could also be controlled by Airborne Remote Control Officers onboard the Hercules. After performing their surveillance mission the Lightening Bugs deployed their parachutes and were scooped up by helicopters under the guidance of “Drone Recovery Officers.”

In May of 1964, the U.S. first began to consider sending drones to replace its U-2s in spying missions over Cuba. Lightning Bugs flown by U.S. Strategic Air Command were subsequently used for surveillance in so-called “denied areas” across an increasingly widening Cold War battlespace: including Cuba, North Korea, and the People’s Republic of China. In November 1964, The Washington Daily News reported that, “Communist China claimed to have shot down a U.S. reconnaissance plane with no pilot.” Time also reported that, “Communist China held an official ceremony celebrating a “major victory” in the shooting down of ‘a pilotless, high-altitude reconnaissance military plane of U.S. imperialism’ over Central-South China.” The U.S. military remained quiet about the wreckage from the secret project: much like it would decades later after the Iranians captured an advanced CIA drone.

Lightning Bugs were widely used over North Vietnam after Rolling Thunder officially ended in 1968. The “electronic battlefield” of the Vietnam War is pivotal to understanding the development of contemporary drone warfare. It marked the turning point in which drones morphed from being “targets” to remote “sensor” platforms that could survey the landscape below. According to Col. John Dale, who was director for Strategic Air Command’s 15th Air Force headquarters, the Lightning Bugs continually confounded MiG fighters over China, North Korea, and Vietnam, by flying at very low altitudes. As Dale stated, “from October 1968 to November 1972 – four years – we were the only aircraft flying in North Vietnam,” adding that thanks to CIA support, “we were able to do so much for so long, because there weren’t any politicians involved.”

The robotic eyes in the sky were successful. “In Vietnam, the 147 drones [Lightning Bugs] were used so extensively and for such a variety of missions that Southeast Asia operations jocularly are referred to as the “Tonkin Gulf Test Range.” Between 1964 and 1975, more than 1,000 Lightning Bugs flew over 34,000 surveillance missions across Southeast Asia. Indeed, “Often unknown to both those who looked at them and those that published them, many of the aerial views of North Vietnam that appeared in the American press were taken by the drones” (Dickson, p.188). South of the seventeenth parallel, drones were being trialed as “electronic listening devices” in Igloo White. This included the QU-22B Beech aircraft (Pave Eagle), a prototype unmanned system that was ultimately beset by too many teething problems. But the war managers were not about to give up: thousands of U.S. airmen had died, and thousands of planes had been destroyed. As the Vietnam War was winding down, the robots were gearing up.

The drone revolution was kickstarted by a May 1970 symposium sponsored by the Air Force and the RAND Corporation. After the second symposium in July, it was decided that the time was ripe for remotely piloted vehicles (RPVs). The Air Force launched the Compass Cope program in the 1970s to increase the range and electronic surveillance capabilities of RPVs. The program involved funding Boeing and Ryan to develop high-altitude, long-endurance drones. These prototypes were the most ambitious unmanned surveillance drones in Air Force history, capable of flying for over 24 hours and piloted from the ground. At the same time that drones were getting bigger– more like the U-2s they were replacing–a range of “mini-RPVs” were developed. An example would be the Praeire prototypes, which were capable of carrying laser designators and TV cameras. In addition to surveillance drones, the Air Force began experimenting with weaponized Firebees. In May of 1973, the Philco-Ford Corporation developed a laser designator that could be attached to a Ryan BGM-34B Firebee drone, with the aim of creating a “strike drone.”

The 1970s were defined by a mixture of unease, skepticism, speculation, and outright hyperbole about the end of the human pilot. Some of the unease stemmed from the day a human pilot was “defeated” by a drone. In 1971, a Ryan official challenged John Smith, then commander of the Navy Fighter Weapons “Top Gun” School to fly against a drone. The F-4 Phantom and its pilot could not keep pace with the inhuman twists and turns the robot was pulling.C ontrolled by pilots on the ground, the Firebee managed to score several “hits” on the F-4 The 1980s saw the robotic torch pass to Israel. It used Pioneer drones in the early 1980s against Syrian forces, leading to the formation of the joint Pioneer UAV Corporation (uniting Israel Aircraft Industries with the AAI Corporation). Nearly all the pieces were in place for the Predator Empire. Except, of course, the Predator. It would take decades before the next phase: the drone as weapon.

In the next section, I want to explore this phase, tracing the historical rise of the Predator drone, beginning in the 1980s. In particular, I want to explore how the American drone became an object of power in tandem with a series of legal objects. While advancements in drones were driven by the requirements of cartographic intelligence, these unmanned objects were very much bound to a series of legal objects that enabled their deployment. In other words, the relationship between technology and law is extremely important in charting the rise of the Predator drone: both come together in the production of geographic knowledge and surveillance, target acquisition, and wider economies of life and death. This relationship between technology and law is embodied in two contrasting figures that did more than most to fuel the motors of the Predator Empire: An Israeli engineer called Abraham Karem and a Saudi jihadist called Osama bin Laden.

The Birth of the Predator

“Rare is the technology that can change the face of warfare. In the first half of the past century, tanks and planes transformed how the world fought its battles. The fifty years that followed were dominated by nuclear warheads and ICBMs, weapons of such horrible power that they gave birth to new doctrines to keep countries form ever using them. The advent of the armed drone upended this calculus: War was possible exactly because it seemed so free of risk. The bar for war had been lowered, the remote-controlled age had begun, and the killer drones became an object of fascination inside the CIA”. (Mark Mazzetti, 2012, ‘The Way of the Knife’, p. 100)

Abraham Karem was born in Baghdad, the son of a Jewish merchant. His family moved to Israel in 1951, and by the 1970s, the young Karem was already building aircraft for the Israeli Air Force, during which time aviation engineers were attempting to satisfy the need for real-time intelligence. In 1980 he emigrated from Israel to Los Angeles and started to build aircraft in his garage. A year later he wheeled out a bizarre, cigar-looking aircraft called the ‘Albatross’ that would change the face of warfare forever.

At Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, Karem demonstrated that his Albatross could stay in the air for 56 hours straight. This was somewhat of a revelation. During the Vietnam War, U.S. drones were programmed to fly a pre-programmed route and take still-photographs. But they could only stay in the air for around two hours. The flight of the Albatross led to funding from DARPA, the military’s research and development department. The first outcome from this seed money was a drone called the Amber, developed by Karem’s company Leading Systems Incorporated. Although the Amber enjoyed much success, including demonstrating a flight endurance of 40 hours by 1988, it soon became apparent that the Amber was insufficient for prolonged surveillance: it was unable to carry large quantities of fuel or sophisticated sensor equipment. Leading Systems responded to this deficiency by rolling out the GNAT-750 in 1989. The GNAT improved on the Amber in a number of ways: it was equipped with GPS navigation, which allowed for autonomous missions of up to 48 hours, and also housed infrared and low-light cameras in a moveable sensor turret under its nose.

Karem’s company found itself in fiscal trouble when the military decided not to pursue large-scale development of the Amber. The U.S. Congress had become impatient with UAV development, and by 1990, the Pentagon was forced to consolidate its UAV research into a single Joint Program Office, which wasn’t budgeted for any research. Congress also banned DARPA from supporting UAV projects outside of the jurisdiction of the Pentagon’s JPO, which effectively killed off UAV development, including the embryonic Amber and GNAT programs. Financially stretched, Karem sold his company to Hughes Aircraft, which in turn sold it to San Diego-based General Atomics in 1990. General Atomics decided to continue development of the GNAT-750, and Karem was made part of the company’s subsidiary called General Atomics Aeronautical Systems.

In 1993, three years after General Atomics assimilated Karem’s team, the Pentagon issued a requirement to support UN peacekeeping forces in the former Yugoslavia. What is often referred to as the Bosnian war took place between 1992 and 1995, and resulted in around 100,000 people killed, tens of thousands of women raped, and millions more displaced. In the serenity of the skies however, the GNAT-750 was flown to provide overhead surveillance for NATO convoys and for spotting Serbian artillery.

Because of the urgent need for surveillance as the war unfolded, existing, cumbersome, military acquisition procedures were controversially skipped over. The CIA was able to circumvent the Congressional block on UAV development because it operated outside of military jurisdiction. To recall, drone development in the military been effectively halted through the Congressional JPO. And this presented the perfect opportunity for the CIA. By 1993 the agency had become frustrated with poor quality satellite intelligence over Bosnia. Woolsey, then director of the CIA, was already acquainted with Karem, and looked to General Atomics for a plane that could provide a persistent aerial presence and real-time surveillance. Under the codename LOFTY VIEW, the CIA would operate the GNAT-750 in total secrecy. The GNAT first flew over Bosnia in February of 1994 from nearby Albania (according to Mark Mazzetti – the hangar was rented in exchange for two trucloads of wool blankets, and money came from Representative Charlie Wilson). According to the CIA director, “I could sit in my office, call up a classified channel and in an early version of e-mail type messages to a guy in Albania asking him to zoom in on things”.

But codename LOFTY VIEW was not a real success. The GNAT was vulnerable to inclement weather. And the biggest impediment was the communication device housed in the aircraft’s fuselage: the C-band line-of-sight data link only had a range of around 150 nautical miles. This meant that the drone could only be controlled from a relatively close proximity; seriously restrict its surveillance capabilities. The CIA initially tried to overcome this by using an intermediary aircraft to relay the data, thereby extending the flight orbit of the GNAT. But this relay did not solve the GNAT’s data problems. The surveillance imagery produced simply had too far to travel: from a GNAT-750, to a relay aircraft, to a ground station in Albania, to a satellite circulating the planet, and then finally, onwards to the CIA headquarters in Langley.

Atomics responded with the Predator. The Predator drone extended the GNAT’s limited range with the addition of a Ku-band SATCOM data ink. The new satellite communications overcame the limited data link of the GNAT and the limitations of the C-band line-of-sight. In fact, a SATCOM link meant that American drone operators didn’t even have to be in same region or even continent as the drone. The Predator drones were first flown in June 1994, and were deployed to the Balkans under Operation Nomad Vigil and Operation Deliberate Force in 1995, the latter the name for the NATO air campaign against Bosnian Serb forces. Both the GNAT-750 and its offspring the Predator served simultaneously due the massive demand placed on surveillance aircraft. Future developments of the Predator included a de-icing system, reinforced wings, and a laser-guided targeting system: the latter two improvements were essential for weaponising the drone in its later life.

In 1995 Predators were shown in an aviation demonstration at Fort Bliss. Impressed by the drone’s capabilities, the U.S. Air Force soon established its very first UAV squadron, the 11th Reconnaissance Squadron at Indian Springs Auxiliary Airfield in Nevada, later named as Creech Air Force Base in 2005. Creech remains the current hub of American drone operations in Afghanistan.

After the CIA’s Predator drone spotted who it believed was bin Laden at Tarnak Farm, Afghanistan, in 2000 (more on this below), research went into shortening the kill-chain: getting Tomahawk missiles to fly from a submarine in the Arabian Sea to southern Afghanistan would take six hours to go through military protocols. The Predator’s Hellfire was the solution. At Indian Springs, Nevada, a program was born under the Air Force’s “Big Safari” office, a classified division in charge of developing secret intelligence programs for the military. In 2001 tests were made early in the year to turn the hunter into a killer.

In sum, what started in Abraham Karem’s Los Angeles garage as a funny-looking Albatross had become a Predator drone with global ambitions. And war would never quite be the same. But this is only half of the story.

A Tall Man in Robes

Osama bin Laden moved from Saudi Arabia to Peshawar, Pakistan in or around July of 1986. He was a well-known figure among Muslim Brotherhood-connected rebels, and helped finance the Afghan mujahideen, opening his first training facility in the same year.

By this time, the CIA had also funnelled millions of dollars to Afghan jihadists for half a decade (see Coll, 2004). Under Ronald Reagan’s Cold War warriors, the CIA had directly and indirectly aggrandized violent figures such as Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Jalaluddin Haqqani. The latter figure, a respected Pashtun commander, had full CIA support, and his organization—the Taliban-linked Haqqani network—would later re-emerge as a terrorist organization and drone target in the ‘war on terror’.

By the early 1990s, bin Laden was certainly on the CIA’s radar, but Afghanistan, increasingly, was not. As the Cold War thawed, counter-terrorist activity and human intelligence in the region faded, leaving a massive blind-spot in the agency’s knowledge. When President Clinton signed Executive Order 12947 in 1995, which imposed sanctions against 12 terrorist groups around the world, neither al-Qaeda nor bin Laden made the list.

There was one exception to this intelligence malaise: the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center (CTC). The CTC was established in 1986, under the Directorate of Operations, and was designed to unify the disparate regional intelligence knowledges of the CIA’s station bureaus. In recognition of bin Laden’s growing importance to global terrorist operations, in January 1996 the CTC opened a new ‘desk’ solely to track him down. By this time, bin Laden had ingratiated himself with the Afghan Taliban, whose brutal regime ruled Kabul between 1996 and 2001. On February 23, 1998, bin Laden—previously known to the CIA as a financier rather than strategist—unveiled a key fatwa from his organization, the World Islamic front, called “The International Islamic Front for Jihad Against Jews and Crusaders”. The CIA viewed bin Laden’s escalating rhetoric, which called for the indiscriminate killing of Americans and Jews, with deep concern. After two American embassies in Africa were bombed in 1998, Clinton announced that bin Laden had launched a ‘terrorist war’ against the U.S. In retaliation to these bombings in Tanzania and Kenya, the American President approved the launch of seventy-five tomahawk missiles at Afghanistan. The missiles missed bin Laden, but did kill twenty or so militants. The hunt was still on.

During this time, the legality of bin Laden’s assassination was a constant discussion point. The CIA’s official legal authority to conduct covert operations stems from the powerful precedent of Executive Order 12333, signed by President Ronald Reagan in 1981, to “Conduct counterintelligence activities outside the United States” (1.8.C). However, the same act (2.11) states that “No person employed by or acting on behalf of the United States Government shall engage in, or conspire to engage in, assassination”. This long-standing ban on U.S. assassinations was relaxed by President Clinton in a 1998 Presidential Finding (or Memorandum of Notification) that allowed some lethal force against bin Laden and his lieutenants in Afghanistan. There remains confusion as to the actual wording and prescription of this Presidential finding due to the legal and bureaucratic debate surrounding whether or not bin Laden’s assassination was in violation of international law. By early 1999, George Tenet, director of the CIA, had become increasingly frustrated by the lack of attention given to the growing threat of al-Qaeda in Clinton’s cabinet. By now the CTC estimated that al-Qaeda was operating in 60 countries. Tenet had a plan to hunt bin Laden down, which came to be known as The Plan. He named Cofer Black as head of the CTC, and sought to focus CIA resources on al-Qaeda. His hire symbolized a more ‘kinetic’ of ‘paramilitary’ response to bin Laden. The gloves were coming off.

A Missed Opportunity

The CIA did have a history with drones prior to the Predator. In the first years of the agency’s CTC, its founding director, Dewey Clarridge, had sought drones to help search for American hostages in restricted areas of Beirut and Lebanon. Clarridge had also experimented with arming the drones with small rockets, but they were too inaccurate for their purpose. When the Air Force began demanding fast, jet-like drones in the 1990s, the CIA wasn’t interested: they preferred smaller drones that could take pictures in situations where satellites or spy planes could not. When the CIA secretly embraced the Predator drone in 1993, many in the Air Force were unhappy. But ultimately, the CIA arranged for Air Force teams trained by the Eleventh Reconnaissance Squadron at Nellis Air Force base to operate the agency’s clandestine drones. The Predator’s ability to hover above a target for hours, relaying high-resolution live surveillance, was invaluable.

Not everyone in the CIA was sold. Some saw the Predator as a technological fix that undermined the value of human-intelligence. As these bureaucratic debates raged on in the summer of 2000, Cofer Black, head of the CTC, was determined to weaponize the drone with an air-to-ground missile called a Hellfire. That very same summer, Uzbekistan agreed to allow Predator flights over Afghanistan from one of its own air bases. Despite the secrecy of this deal, the Uzbek government and the CIA were both extremely nervous that the control stations and vans used by CIA flight operators would attract unwanted attention. To address this problem, the Predator’s extended SATCOM data link enabled it to be controlled remotely from outside of Uzbekistan. Clinton agreed with this long-range solution, approving a limited ‘proof of concept mission’. This involved the bin Laden unit drawing up plans for 15 Predator flights, each lasting for just over twenty four hours, during which the drones surveyed bin Laden’s known haunts in Southern and Eastern Afghanistan. They wouldn’t have to wait long.

While loitering over Tarnak Farm near Kandahar on September 7th, 2000, the Predator photographed what appeared to be bin Laden: a tall man dressed in Arab robes surrounded by a ring of armed bodyguards. Almost a year before the 9/11 attacks, the Predator had captured what the agency strongly believed to be the al-Qaeda leader. But at this time, the Predator was just a surveillance plane. And as winter fell in December, winds gathered in North Afghanistan and the Predator’s small engine struggled to fight the headwind gusts, which forced the drone to keep drifting back towards Uzbekistan. The CTC had no choice but to halt the operation. During this hiatus, Cofer Black hoped that lawyers would allow the CIA to fix missiles to the Predators. After years of searching, they had probably located bin Laden at Tarnak Farm, but were unable to take the shot. And yet, Tarnak Farm inside of Afghanistan was a complicated legal and ethical target. Clinton’s administration still had not labelled the Taliban a terrorist organization, and other government officials worried about the geopolitical fallout from striking a target that housed civilians—estimated to include perhaps one hundred women and children. For now at least, the Predator remain leashed.

In February 2001, under a newly elected Bush Administration, the U.S. State department’s lawyers waived concerns that an armed drone might violate the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. This legislation was signed in 1987 by Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, and prevented ground launched ballistic and cruise missiles. As well as rubber stamping the Predator program, Hellfire missiles tests were successfully completed in exercises conducted in May and June. But the Bush administration wasn’t completely sold on drones or on Afghanistan, despite lobbying by the CIA.

By now of course, the armed Predator was virtually a CIA invention: a technology that perfectly embodied the agency’s desire to survey in secret from high in the sky. And yet, even by July 2001, the U.S. went on record to denounce Israel’s use of targeted killings. The U.S. ambassador to Israel said: “The United States government is very clearly on record as against targeted assassinations.… They are extrajudicial killings and we do not support that.”

Hellfire

“Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S.” was the headline written across President Bush’s Daily Brief as it was presented to him at his Texas ranch on the 6th of August. 9 days later, Cofer Black said “We are going to be struck soon” at the Pentagon’s classified annual conference. “Many Americans are going to die, and it could be in the U.S.” On September 4, 2001, in an important cabinet meeting, the director of the CIA presented the agency’s plan to operate the Predator drone – a lethal operation usually entrusted to the U.S. Air Force. In early September, Condoleezza Rice agreed with the CIA that an armed Predator was needed, but for now the agency should only pursue reconnaissance Predator flights in Afghanistan.

This changed just a week later. The armed Predator program was activated days after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, with Predators reaching Afghanistan by September 16th 2001, and armed Predators reaching the country on October 7th.

After 9/11 the CIA was authorized to take the “gloves off”, in the infamous words of Cofer Black. President Bush signed a directive that created a secret list of High Value Targets (HVTs) that the CIA was authorized to kill without further Presidential approval. The same broad-brush finding also enabled “disappearances” and the infamous network of global prisons and extraordinary rendition. John Rizzo, the former acting General Counsel of the CIA, authorized the finding. He said it allowed activities that were “unprecedented in my 25 years of experience at CIA” (quoted in PBS, 2011). The retired legal chief added, “Frankly, the finding was so aggressive and comprehensive that honestly there wasn’t much more that could have been added.”

The first ever CIA drone attack was a disaster. The baptismal strike occurred on the 4th of February 2002. The agency’s Predator unleashed a Hellfire missile at a “tall man” and his lieutenants near the city of Khost, believing the man to be none other than bin Laden. But the analysts had acquired the wrong target. This time, it was innocent civilians gathering up scrap metal. All were killed. Perhaps in a mark of supreme irony that defines the drone wars more generally, the site of the strike was Zhawar Kili, a mujahideen complex built by Haqqani in the 1980s with CIA support. A further irony is just how short the drones were initially deployed in Afghanistan after years of lobbying. By April 2002, American focus had already switched to the mounting invasion of Iraq. Even if the Predators had left the country, the precedent was set: the Afghan Predator program was to become the model for far deadlier CIA activity in Pakistan.

On November 4, 2002, there was the first CIA targeted killing outside of a declared war zone using the “sweeping authority” given to the spy agency by Bush in September 2001. The target was Al-Harethi, mastermind of the USS Cole bombing. Yemeni President Saleh was an “easy sell” for drone strikes: after al-Harethi was killed, the the Yemeni government claimed responsibility. But later in 2002 it leaked that the US was behind it Saleh was furious and banned drones, which wouldn’t re-emerge in the country until 2010 with Yemen in turmoil. By then Saleh was in no position to object.

Richard Clarke, who served in both Clinton and Bush administrations as the top White House counterterrorism official, conducted a review of spying operations in Afghanistan, consulting longtime CIA analyst Allen. Unlike agency director George Tenet and head of Operations Pavitt, Allen was a fierce Predator advocate. Allen was told about secret Air Force tests in the desert: there was a chance, according to Pentagon officials, that the CIA could find bin Laden using a drone. Allen brought the Predator idea back to Richard Clarke. Figuring that Tenet and Pavitt would be against the idea, they went straight to the White House, inviting advocates Black, Allen, and Richard Blee, (head of the CTC’s bin Laden hunting unit – code name Alec Station).