SOURCE :https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_weapon

PART - 2 of 3

****************************************

CLICK TO READ

( A ) PART ONE of THREE PARTS -

http://bcvasundhra.blogspot.in/2016/01/nukes-nuclear-weapon.html

( B ) PART THREE of THREE PARTS -

http://bcvasundhra.blogspot.in/2016/01/source-non-weapons-uses-main-article.html

****************************************

Because of the immense military power they can confer, the political control of nuclear weapons has been a key issue for as long as they have existed; in most countries the use of nuclear force can only be authorized by the head of government orhead of state.[29] Controls and regulations governing nuclear weapons are man-made, and so are imperfect. Therefore, there is an inherent danger of "accidents, mistakes, false alarms, blackmail, theft, and sabotage".[30]

PART - 2 of 3

****************************************

CLICK TO READ

( A ) PART ONE of THREE PARTS -

http://bcvasundhra.blogspot.in/2016/01/nukes-nuclear-weapon.html

( B ) PART THREE of THREE PARTS -

http://bcvasundhra.blogspot.in/2016/01/source-non-weapons-uses-main-article.html

****************************************

Nuclear strategy

Main articles: Nuclear strategy and Deterrence theory

See also: Nuclear peace, Essentials of Post–Cold War Deterrence, Single Integrated Operational Plan, nuclear warfare and On Thermonuclear War

Nuclear warfare strategy is a set of policies that deal with preventing or fighting a nuclear war. The policy of trying to prevent an attack by a nuclear weapon from another country by threatening nuclear retaliation is known as the strategy of nuclear deterrence. The goal in deterrence is to always maintain a second strike capability (the ability of a country to respond to a nuclear attack with one of its own) and potentially to strive for first strike status (the ability to completely destroy an enemy's nuclear forces before they could retaliate). During the Cold War, policy and military theorists in nuclear-enabled countries worked out models of what sorts of policies could prevent one from ever being attacked by a nuclear weapon, and developed weapon game theory models that create the greatest and most stabledeterrence conditions.

Different forms of nuclear weapons delivery (see above) allow for different types of nuclear strategies. The goals of any strategy are generally to make it difficult for an enemy to launch a pre-emptive strike against the weapon system and difficult to defend against the delivery of the weapon during a potential conflict. Sometimes this has meant keeping the weapon locations hidden, such as deploying them on submarines or land mobile transporter erector launchers whose locations are very hard for an enemy to track, and other times, this means protecting them by burying them in hardened missile silobunkers.

Other components of nuclear strategies have included using missile defense (to destroy the missiles before they land) or implementation of civil defense measures (using early-warning systems to evacuate citizens to safe areas before an attack).

Note that weapons designed to threaten large populations, or to generally deter attacks are known as strategic weapons.Weapons designed for use on a battlefield in military situations are called tactical weapons.

There are critics of the very idea of nuclear strategy for waging nuclear war who have suggested that a nuclear war between two nuclear powers would result in mutual annihilation. From this point of view, the significance of nuclear weapons is purely to deter war because any nuclear war would immediately escalate out of mutual distrust and fear, resulting in mutually assured destruction. This threat of national, if not global, destruction has been a strong motivation for anti-nuclear weapons activism.

Critics from the peace movement and within the military establishment[citation needed] have questioned the usefulness of such weapons in the current military climate. According to an advisory opinion issued by the International Court of Justice in 1996, the use of (or threat of use of) such weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, but the court did not reach an opinion as to whether or not the threat or use would be lawful in specific extreme circumstances such as if the survival of the state were at stake.

Another deterrence position in nuclear strategy is that nuclear proliferation can be desirable. This view argues that, unlike conventional weapons, nuclear weapons successfully deter all-out war between states, and they succeeded in doing this during the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.[21] In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Gen. Pierre Marie Gallois of France, an adviser to Charles DeGaulle, argued in books like The Balance of Terror: Strategy for the Nuclear Age(1961) that mere possession of a nuclear arsenal, what the French called the force de frappe, was enough to ensure deterrence, and thus concluded that the spread of nuclear weapons could increase international stability. Some very prominent neo-realist scholars, such as the late Kenneth Waltz, formerly a Political Science at UC Berkeley and Adjunct Senior Research Scholar at Columbia University, and John Mearsheimer of University of Chicago, have also argued along the lines of Gallois. Specifically, these scholars have advocated some forms of nuclear proliferation, arguing that it would decrease the likelihood of total war, especially in troubled regions of the world where there exists a unipolar nuclear weapon state. Aside from the public opinion that opposes proliferation in any form, there are two schools of thought on the matter: those, like Mearsheimer, who favor selective proliferation,[22] and those of Kenneth Waltz, who was somewhat more non-interventionist.[23][24]

The threat of potentially suicidal terrorists possessing nuclear weapons (a form of nuclear terrorism) complicates the decision process. The prospect of mutually assured destruction may not deter an enemy who expects to die in the confrontation. Further, if the initial act is from a stateless terrorist instead of a sovereign nation, there is no fixed nation or fixed military targets to retaliate against. It has been argued by the New York Times, especially after the September 11, 2001 attacks, that this complication is the sign of the next age of nuclear strategy, distinct from the relative stability of the Cold War.[25] In 1996, the United States adopted a policy of allowing the targeting of its nuclear weapons at terrorists armed with weapons of mass destruction.[26]

Robert Gallucci, president of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, argues that although traditional deterrence is not an effective approach toward terrorist groups bent on causing a nuclear catastrophe, Gallucci believes that “the United States should instead consider a policy of expanded deterrence, which focuses not solely on the would-be nuclear terrorists but on those states that may deliberately transfer or inadvertently lead nuclear weapons and materials to them. By threatening retaliation against those states, the United States may be able to deter that which it cannot physically prevent.”.[27]

Graham Allison makes a similar case, arguing that the key to expanded deterrence is coming up with ways of tracing nuclear material to the country that forged the fissile material. “After a nuclear bomb detonates, nuclear forensics cops would collect debris samples and send them to a laboratory for radiological analysis. By identifying unique attributes of the fissile material, including its impurities and contaminants, one could trace the path back to its origin.”[28] The process is analogous to identifying a criminal by fingerprints. “The goal would be twofold: first, to deter leaders of nuclear states from selling weapons to terrorists by holding them accountable for any use of their own weapons; second, to give leader every incentive to tightly secure their nuclear weapons and materials.”[28]

Governance, control, and law

Main articles: Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, START I, Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty, Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty and New START

Because of the immense military power they can confer, the political control of nuclear weapons has been a key issue for as long as they have existed; in most countries the use of nuclear force can only be authorized by the head of government orhead of state.[29] Controls and regulations governing nuclear weapons are man-made, and so are imperfect. Therefore, there is an inherent danger of "accidents, mistakes, false alarms, blackmail, theft, and sabotage".[30]

In the late 1940s, lack of mutual trust was preventing the United States and the Soviet Union from making ground towards international arms control agreements. The Russell–Einstein Manifesto was issued in London on July 9, 1955 by Bertrand Russell in the midst of the Cold War. It highlighted the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and called for world leaders to seek peaceful resolutions to international conflict. The signatories included eleven pre-eminent intellectuals and scientists, including Albert Einstein, who signed it just days before his death on April 18, 1955. A few days after the release, philanthropist Cyrus S. Eaton offered to sponsor a conference—called for in the manifesto—in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, Eaton's birthplace. This conference was to be the first of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, held in July 1957.

By the 1960s steps were being taken to limit both the proliferation of nuclear weapons to other countries and the environmental effects of nuclear testing. The Partial Test Ban Treaty (1963) restricted all nuclear testing to underground nuclear testing, to prevent contamination from nuclear fallout, whereas the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (1968) attempted to place restrictions on the types of activities signatories could participate in, with the goal of allowing the transference of non-military nuclear technology to member countries without fear of proliferation.

In 1957, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) was established under the mandate of the United Nations to encourage development of peaceful applications for nuclear technology, provide international safeguards against its misuse, and facilitate the application of safety measures in its use. In 1996, many nations signed the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty,[31] which prohibits all testing of nuclear weapons. A testing ban imposes a significant hindrance to nuclear arms development by any complying country.[32] The Treaty requires the ratification by 44 specific states before it can go into force; as of 2012, the ratification of eight of these states is still required.[31]

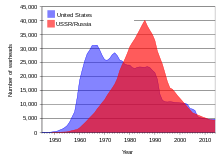

Additional treaties and agreements have governed nuclear weapons stockpiles between the countries with the two largest stockpiles, the United States and the Soviet Union, and later between the United States and Russia. These include treaties such as SALT II (never ratified), START I (expired), INF, START II (never ratified), SORT, and New START, as well as non-binding agreements such as SALT I and the Presidential Nuclear Initiatives[33] of 1991. Even when they did not enter into force, these agreements helped limit and later reduce the numbers and types of nuclear weapons between the United States and the Soviet Union/Russia.

Nuclear weapons have also been opposed by agreements between countries. Many nations have been declared Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones, areas where nuclear weapons production and deployment are prohibited, through the use of treaties. The Treaty of Tlatelolco (1967) prohibited any production or deployment of nuclear weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Treaty of Pelindaba (1964) prohibits nuclear weapons in many African countries. As recently as 2006 a Central Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone was established amongst the former Soviet republics of Central Asia prohibiting nuclear weapons.

In the middle of 1996, the International Court of Justice, the highest court of the United Nations, issued an Advisory Opinion concerned with the "Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons". The court ruled that the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons would violate various articles of international law, including theGeneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions, the UN Charter, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In view of the unique, destructive characteristics of nuclear weapons, the International Committee of the Red Cross calls on States to ensure that these weapons are never used, irrespective of whether they consider them lawful or not.[34]

Additionally, there have been other, specific actions meant to discourage countries from developing nuclear arms. In the wake of the tests by India and Pakistan in 1998, economic sanctions were (temporarily) levied against both countries, though neither were signatories with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. One of the stated casus belli for the initiation of the 2003 Iraq War was an accusation by the United States that Iraq was actively pursuing nuclear arms (though this was soon discovered not to be the case as the program had been discontinued). In 1981, Israel had bombed a nuclear reactor being constructed in Osirak, Iraq, in what it called an attempt to halt Iraq's previous nuclear arms ambitions; in 2007, Israel bombed another reactor being constructed in Syria.

In 2013, Mark Diesendorf says that governments of France, India, North Korea, Pakistan, UK, and South Africa have used nuclear power and/or research reactors to assist nuclear weapons development or to contribute to their supplies of nuclear explosives from military reactors.[35]

Disarmament

Main article: Nuclear disarmament

Nuclear disarmament refers to both the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons and to the end state of a nuclear-free world, in which nuclear weapons are completely eliminated.

Beginning with the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty and continuing through the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, there have been many treaties to limit or reduce nuclear weapons testing and stockpiles. The 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty has as one of its explicit conditions that all signatories must "pursue negotiations in good faith" towards the long-term goal of "complete disarmament". The nuclear weapon states have largely treated that aspect of the agreement as "decorative" and without force.[36]

Only one country—South Africa—has ever fully renounced nuclear weapons they had independently developed. The former Soviet republics of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine returned Soviet nuclear arms stationed in their countries to Russia after the collapse of the USSR.

Proponents of nuclear disarmament say that it would lessen the probability of nuclear war occurring, especially accidentally. Critics of nuclear disarmament say that it would undermine the present nuclear peace and deterrence and would lead to increased global instability. Various American elder statesmen,[37] who were in office during the Cold War period, have been advocating the elimination of nuclear weapons. These officials include Henry Kissinger, George Shultz, Sam Nunn, and William Perry. In January 2010, Lawrence M. Krauss stated that "no issue carries more importance to the long-term health and security of humanity than the effort to reduce, and perhaps one day, rid the world of nuclear weapons".[38]

In the years after the end of the Cold War, there have been numerous campaigns to urge the abolition of nuclear weapons, such as that organized by the Global Zero movement, and the goal of a "world without nuclear weapons" was advocated by United States President Barack Obama in an April 2009 speech in Prague.[39] A CNN poll from April 2010 indicated that the American public was nearly evenly split on the issue.[40]

Some analysts have argued that nuclear weapons have made the world relatively safer, with peace through deterrence and through the stability–instability paradox, including in south Asia.[41][42] Kenneth Waltz has argued that nuclear weapons have helped keep an uneasy peace, and further nuclear weapon proliferation might even help avoid the large scale conventional wars that were so common prior to their invention at the end of World War II.[24] But former Secretary Henry Kissinger says there is a new danger, which cannot be addressed by deterrence: "The classical notion of deterrence was that there was some consequences before which aggressors and evildoers would recoil. In a world of suicide bombers, that calculation doesn’t operate in any comparable way".[43] George Shultz has said, "If you think of the people who are doing suicide attacks, and people like that get a nuclear weapon, they are almost by definition not deterrable".[44]

Further information: See List of states with nuclear weapons for statistics on possession and deployment

Peace movements emerged in Japan and in 1954 they converged to form a unified "Japanese Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs". Japanese opposition to nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific Ocean was widespread, and "an estimated 35 million signatures were collected on petitions calling for bans on nuclear weapons".[60]

See also: Global Positioning System, Nuclear weapons delivery, History of computers, ENIAC and Swords to ploughshares

According to an audit by the Brookings Institution, between 1940 and 1996, the U.S. spent $8.78 trillion in present-day terms[66] on nuclear weapons programs. 57 percent of which was spent on building nuclear weapons delivery systems. 6.3 percent of the total, $551 billion in present-day terms, was spent on environmental remediation and nuclear waste management, for example cleaning up the Hanford site, and 7 percent of the total, $617 billion was spent on making nuclear weapons themselves.[67]

United Nations

Main article: United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs

The UN Office for Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) is a department of the United Nations Secretariat established in January 1998 as part of the United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan's plan to reform the UN as presented in his report to the General Assembly in July 1997.[45]

Its goal is to promote nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation and the strengthening of the disarmament regimes in respect to other weapons of mass destruction, chemical and biological weapons. It also promotes disarmament efforts in the area of conventional weapons, especially land mines and small arms, which are often the weapons of choice in contemporary conflicts.

Controversy

See also: Nuclear weapons debate and History of the anti-nuclear movement

Ethics

Even before the first nuclear weapons had been developed, scientists involved with the Manhattan Project were divided over the use of the weapon. The role of the two atomic bombings of the country in Japan's surrender and the U.S.'s ethical justification for them has been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades. The question of whether nations should have nuclear weapons, or test them, has been continually and nearly universally controversial.[46]

Notable nuclear weapons accidents

- February 13, 1950: a Convair B-36B crashed in northern British Columbia after jettisoning a Mark IV atomic bomb. This was the first such nuclear weapon loss in history.

- June 7, 1960: the 1960 Fort Dix IM-99 accident destroyed a Boeing CIM-10 Bomarc nuclear missile and shelter and contaminated the BOMARC Missile Accident Site in New Jersey.

- January 24, 1961: the 1961 Goldsboro B-52 crash occurred near Goldsboro, North Carolina. A B-52 Stratofortress carrying two Mark 39 nuclear bombs broke up in mid-air, dropping its nuclear payload in the process.[47][48]

- 1965 Philippine Sea A-4 crash, where a Skyhawk attack aircraft with a nuclear weapon fell into the sea.[49] The pilot, the aircraft, and the B43 nuclear bomb were never recovered.[50] It was not until 1989 that the Pentagon revealed the loss of the one-megaton bomb.[51]

- January 17, 1966: the 1966 Palomares B-52 crash occurred when a B-52G bomber of the USAF collided with a KC-135 tanker during mid-air refuelling off the coast of Spain. The KC-135 was completely destroyed when its fuel load ignited, killing all four crew members. The B-52G broke apart, killing three of the seven crew members aboard.[52] Of the four Mk28 type hydrogen bombs the B-52G carried,[53] three were found on land near Almería, Spain. The non-nuclear explosives in two of the weapons detonated upon impact with the ground, resulting in the contamination of a 2-square-kilometer (490-acre) (0.78 square mile) area by radioactive plutonium. The fourth, which fell into the Mediterranean Sea, was recovered intact after a 2½-month-long search.[54]

- January 21, 1968: the 1968 Thule Air Base B-52 crash involved a United States Air Force (USAF) B-52 bomber. The aircraft was carrying four hydrogen bombswhen a cabin fire forced the crew to abandon the aircraft. Six crew members ejected safely, but one who did not have an ejection seat was killed while trying to bail out. The bomber crashed onto sea ice in Greenland, causing the nuclear payload to rupture and disperse, which resulted in widespread radioactive contamination.

Nuclear testing and fallout

Main article: Nuclear fallout

See also: Downwinders

Over 500 atmospheric nuclear weapons tests were conducted at various sites around the world from 1945 to 1980.Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when the Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb test at the Pacific Proving Grounds contaminated the crew and catch of the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon.[55]One of the fishermen died in Japan seven months later, and the fear of contaminated tuna led to a temporary boycotting of the popular staple in Japan. The incident caused widespread concern around the world, especially regarding the effects ofnuclear fallout and atmospheric nuclear testing, and "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries".[55]

As public awareness and concern mounted over the possible health hazards associated with exposure to the nuclear fallout, various studies were done to assess the extent of the hazard. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/ National Cancer Institute study claims that fallout from atmospheric nuclear tests would lead to perhaps 11,000 excess deaths amongst people alive during atmospheric testing in the United States from all forms of cancer, including leukemia, from 1951 to well into the 21st century.[56][57] As of March 2009, the U.S. is the only nation that compensates nuclear test victims. Since the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990, more than $1.38 billion in compensation has been approved. The money is going to people who took part in the tests, notably at the Nevada Test Site, and to others exposed to the radiation.[58][59]

Public opposition

Peace movements emerged in Japan and in 1954 they converged to form a unified "Japanese Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs". Japanese opposition to nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific Ocean was widespread, and "an estimated 35 million signatures were collected on petitions calling for bans on nuclear weapons".[60]

In the United Kingdom, the first Aldermaston March organised by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament(CND) took place at Easter1958, when, according to the CND, several thousand people marched for four days from Trafalgar Square, London, to the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment close to Aldermaston in Berkshire, England, to demonstrate their opposition to nuclear weapons.[61][62] The Aldermaston marches continued into the late 1960s when tens of thousands of people took part in the four-day marches.[60]

In 1959, a letter in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists was the start of a successful campaign to stop the Atomic Energy Commissiondumping radioactive waste[quantify] in the sea 19 kilometres from Boston.[63] In 1962, Linus Pauling won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work to stop the atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons, and the "Ban the Bomb" movement spread.[46]

In 1963, many countries ratified the Partial Test Ban Treaty prohibiting atmospheric nuclear testing. Radioactive fallout became less of an issue and the anti-nuclear weapons movement went into decline for some years.[55][64] A resurgence of interest occurred amid European and American fears of nuclear war in the 1980s.[65]

Costs and technology spin-offs

See also: Global Positioning System, Nuclear weapons delivery, History of computers, ENIAC and Swords to ploughshares

According to an audit by the Brookings Institution, between 1940 and 1996, the U.S. spent $8.78 trillion in present-day terms[66] on nuclear weapons programs. 57 percent of which was spent on building nuclear weapons delivery systems. 6.3 percent of the total, $551 billion in present-day terms, was spent on environmental remediation and nuclear waste management, for example cleaning up the Hanford site, and 7 percent of the total, $617 billion was spent on making nuclear weapons themselves.[67]

CLICK TO READ

( A ) PART ONE of THREE PARTS -

http://bcvasundhra.blogspot.in/2016/01/nukes-nuclear-weapon.html

( B ) PART TWO of THREE PARTS -

http://bcvasundhra.blogspot.in/2016/01/nukes-nuclear-weapons.html

( C ) PART THREE of THREE PARTS -

http://bcvasundhra.blogspot.in/2016/01/source-non-weapons-uses-main-article.html

( A ) PART ONE of THREE PARTS -

http://bcvasundhra.blogspot.in/2016/01/nukes-nuclear-weapon.html

( B ) PART TWO of THREE PARTS -

http://bcvasundhra.blogspot.in/2016/01/nukes-nuclear-weapons.html

( C ) PART THREE of THREE PARTS -

http://bcvasundhra.blogspot.in/2016/01/source-non-weapons-uses-main-article.html

No comments:

Post a Comment