‘In war there are no runners up’.

CDS

Part 30 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/11/cds-jointness-pla-part-central-theater.html

Part 29 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/11/part-29-cds-jointness-pla-strategic.html

Part 28 of N Parts

Part 27of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/10/chinas-future-naval-base-in-cambodia.html

Part 26 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/10/part-26-cds-jointness-pla-n-strategic.html

Part 25 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/10/part-25-cds-jointness-pla-southern.html

Part 24 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/10/part-24-cds-jointness.html

Part 23 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/10/part-22-cds-jointness-pla-chinas-three.html

Part 22 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/05/peoples-liberation-army-deployment-in.html

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/09/cds-part-9-cds-jointness-pla-part-x-of.html

Part 16 TO Part 20 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/10/part-16-to-part-20-cds-jointness-list.htmlPart 15 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/09/cds-part-10-pla-q-mtn-war-himalayan.html

Part 14 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/09/cds-jointness-pla-part-x-of-n-parts-new.html

Part 13 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/09/cda-jointness-pla-pla-system-of-systems.html

Part 12 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/09/part-12-cds-jointness-pla-military.html

Part 11 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/09/china-defense-white-papers1995.html

Part 10 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/09/part-10-cds-jointness-pla-series.html

Part 9 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/08/cds-part-8-making-cds-effective-is.html

Part 8 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/09/cda-part-goldwater-nichols-department.html

Part 7 of N Parts

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/08/cds-part-6-chief-of-defence-staff-needs.html

Part 6 of N Parts:

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/08/the-constitutional-provisions-for.html

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/08/part-4-cds-or-gateway-to-institutional.html

Part 4 of N Parts:

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/08/chief-of-defence-staff.html

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/08/fighting-separately-jointness-and-civil.html

Part 2 of N Parts:

https://bcvasundhra.blogspot.com/2019/08/jointness-in-strategic-capabilities-can.html

SOURCE:

https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-chief-of-defence-staff-needs-an-enabling-institutional-structure/article29278807.ece

https://cenjows.gov.in/pdf/Reforming-and-Restructuring-Higher_.pdf

SECOND

THIRD PART OF THREE PARTS

The Chief of Defence Staff needs an

Enabling Institutional Structure

REFORMING AND

RESTRUCTURING : HIGHER

DEFENCE ORGANIZATION

OF INDIA

By

Brigadier (Dr.) Rajeev Bhutani (Retd)

The Higher Defence Organization of India is a legacy of the

British but its evolution over last 70 years has been reactive,

amateurish in nature and based on adhocism. While our political

leaders and the elite visualize India as a ‘Great Power’ among

the comity of nations but their efforts are not adequate to turn

this vision into reality, particularly in terms of Military Power.

The Military not only needs to be equipped and modernized

at a faster pace, though that also remains unsatisfactory but

the military hierarchy is isolated from Policy-making and is

confined to only carrying out directives. This results in Political

leadership at the helm getting second-hand advice, filtered

through bureaucrats. In a democracy, civilian control over the

military is essential but that implies political control and not

bureaucratic control, especially over operational issues, and

that is the norm in all other democratic powers. There is a need

to synergise the efforts of political executives, military leaders

and bureaucracy towards the common goal of evolving a

holistic national security strategy and suitable organization to

implement it. Another aspect is the emerging future battlefield

milieu spread over land, sea, air, space and cyber domain.

Any delay in preparing ourselves for facing the threats and

challenges in any of these domains will be detrimental to our

national security.

Keeping in step with our rising ‘economic

power’ and ‘smart power’, our military capability is in urgent

need of ‘Comprehensive Reforms and Restructuring’.

“In time of war, the military commander should be given a

seat in the Cabinet. He should not, however, have unlimited

power. His judgement and counsel should merely ensure

that statesmen reached the correct decisions.”

- Carl von Clausewitz

The clear-cut demarcation between the ‘state of war’ and ‘state

of peace’ among nations which existed in the pre-1945 era, has

gradually eroded with the role of force in international relations

having undergone revolutionary changes. The disintegration of

Soviet Union has not only brought an end to the Cold War but

it has called into question some aspects of the Clausewitzian

formulations of the role of force. The militarist notion that a

single purely military victory can affect a permanent political

settlement is among the most dangerous and most persistent

delusions. War of the future is not a mere matter of armies but

of entire nations dedicating themselves to the task of survival.

Not lightning victories in the field but the physical, moral and

economic exhaustion of a nation through multifarious means

other than war would ultimately decide the conflict. The “Use of

force without War” either through Proxy war or demonstrative

and deterrent employment of force has come into vogue in

recent years and is going to stay.

The constricted view of treating national defence as

synonymous with national security is no longer valid. National

security encompasses a much broader spectrum of challenges,

threats and responses in a vast arena, where national defence

- in other words military security essentially from external

threats - is a sub-set of national security in its comprehensive

framework.2

This national security framework would involve

political, social, economic, technological and military factors

each interacting on one another, which in other words are the

essential ingredients of a country’s comprehensive national

power (CNP)3

.

The Higher Direction of Defence with its organization in

a country ensures the optimum utilization of its CNP and

seamless coordination between the people, the government

and the armed forces. This is achieved through a synergistic

effort between the political, civil and military elements. In today’s

environment of ‘coercive diplomacy’, diplomacy is conducted

by civil governments and coercion is the business of armed

forces. Hence the continuous projection of the image of armed

forces capabilities in the international arena is a necessity, while

diplomacy is conducted to avoid adverse consequences to our

security and interests without having to use these capabilities.4

It is apparent that India’s present higher defence organization

and civil-military equation is woefully inadequate to meet the

requirements of today and challenges of the future. And the

worst is, the chiefs of staff are independent entities outside the

framework of the government. In all other democratic polities,

they are part and parcel of the government machinery.

The aim of this paper is to study the higher direction of defence

and its organisation in India and assess its suitability to meet

the requirements of national security. To achieve that aim, this

paper addresses the subject in following sequence:

First, Historical Ethos and the British Legacy.

Second, Evolution of Higher Defence Organization in India.

Third, An Appraisal of Higher Defence Organization of Major

Powers.

Fourth, Faultlines in India’s Higher Defence Structure.

Fifth, Reforming and Restructuring:

Inescapability of Integrated

Theatre Commands/ Specified Commands and Chief of the

Defence Staff (CDS).

Historical Ethos and the British Legacy

CHIEF OF DEFENCE STAFF ( CDS )MAURYAN EMPIRE

The concept of Nation State, which was brought into being by

the French Revolution in the West, was prevalent in our country

over two millenniums ago during the days of Chanakya, and

the Mauryan Empire under King Chandragupta had all the

attributes of a modern higher defence organization. According

to Megasthenes, the Greek Ambassador in the court of

Chandragupta, the Mauryan War Office had Commanderin-Chief at the apex with six boards each of five officers for

Cavalry, Chariots, Elephants, Infantry, Commissariat and

Admiralty. This War Office catered for the defence of a country

of continental dimension from Kabul to Kamrup and Kashmir to

Karnataka, looking after the largest standing Army of its time:

600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, 9,000 elephants, 8,000 war

chariots and an unspecified number of naval ships. The most

significant aspect is that it was a combined headquarters for

both the Army and the Navy and there was a common Chief

for the two Services, which in modern parlance could be called

‘Chief of the Defence Staff’5

( See Annexure 1).

But like all other ancient civilisations, we also reached at the pinnacle of glory and power and then declined. Instead of basking in the glory of our ancient past, let this act as a source of inspiration for improving our present organization.

The present higher defense organization in India is a corollary to the legacy left by the British which has undergone certain modifications.

But like all other ancient civilisations, we also reached at the pinnacle of glory and power and then declined. Instead of basking in the glory of our ancient past, let this act as a source of inspiration for improving our present organization.

The present higher defense organization in India is a corollary to the legacy left by the British which has undergone certain modifications.

In the Nineteenth Century, on the one hand, the Commanderin-Chief (C-in-C) as it is evident from the designation, was the

Commander of Armed Forces while on the other hand, the

Military Member, (an officer in the rank of Major General and

junior to the C-in-C) was the channel through whom all the

proposals and recommendations of the C-in-C were being put

up to the Viceroy and all orders of the Viceroy communicated

to the Army. The famous Curzon-Kitchener dispute was not

a case of the Army questioning the superiority of the Civil

but Lord Kitchener, the C-in-C of the Armed Forces in India, argued that the office of the Military Member was “detrimental

to military efficiency”. He proposed the unification of the offices

of the Military Member and the C-in-C into one position. The

British government decided in favour of Kitchener, which led to

resignation of Curzon. Consequently, the post of Military Member

was abolished and the C-in-C became the only member of the

Viceroy’s Executive Council. A Major General was appointed

as the Army Secretary and became the head of the Army

Department. He had to work under the C-in-C. A General Staff

Branch was introduced in the Army Headquarters with Chief

of General Staff (CGS) becoming the Principal Staff Officer

(PSO) of the C-in-C. Later from 1921 onwards, designation

of Army Secretary was changed to Defence Secretary and

officers of the Indian Civil Service were given this appointment

following the advice of Lord Esher. In the early thirties, a Chiefs

of Staff Committee was also established which was presided

over by the CGS with FOC-in-C Navy and AOC Air Force as

members. The latter two were provided direct access to the

C-in-C and the Viceroy in the event of any major differences in

the Committee.6

[ NOTE: WRT TO ABOVE DEFENCE SECRETARY SHOULD WORK UNDER THE COMMAND OF FUTURE VISUALISED CDS -VASUNDHRA ]

This so called higher defence organization had supposedly

stood the test of time in the two World Wars but the fact must

not be lost sight of that national decisions for India were taken

in WhiteHall, London and the British Indian C-in-C was not

even the equivalent of a Chief of Staff of modern democratic

polity who has the responsibility for overall national defence

planning and for making recommendations on that basis to the

Cabinet.

Evolution of Higher Defence Organization in India

On 24 September 1947, Lord Ismay, the Chief of Staff to Lord

Mountbatten, Governor General of India, had recommended

a three-tier Higher Defence Organization, to Prime Minister

Jawahar Lal Nehru, at his request. This was based on his

experience as the Secretary to the Chief of Staff Committee in

the UK, being the Principal Staff Officer of Sir Winston Churchill and after the World War II, he had been to the United States

to help the Americans in reorganising their higher defence

setup. Based on his recommendations, three committees were

formed:

• The Defence Committee of the Cabinet (DCC) chaired by the Prime Minister.

• The Defence Minister’s Committee (DMC) chaired by the Defence Minister.

• The Chiefs of Staff Committee (COSC) as part of the Military Wing of the Cabinet Secretariat. The chairmanship was made rotational with the Service Chief longest in the Committee becoming the Chairman.

This arrangement functioned well till the mid 1950s despite the

C-in-C being only an invitee to the DCC and not a member. The

designation of the C-in-C of the three services was changed to

Chiefs of Staff in 1955, and subsequent to the appointment

of V K Krishna Menon as the Defence Minister in 1957, the

DCC began to lose its relevance as he had direct access to

the PM. After the 1962 debacle, the DCC was first changed

to Emergency Committee of the Cabinet and then to Cabinet

Committee of Political Affairs (CCPA). The 1961 Allocation of

Business (AOB)/Transaction of Business (TOB) Rules were

promulgated and the three services ceased to be a part of the

Ministry of Defence and became attached offices. Thereafter,

the Military Wing was moved out of the Cabinet Secretariat

thereby creating a vacuum between the political and the military

hierarchy.7

If India could manage the hurdles of wars in 1965

and 1971, it was more to the credit of the then prime ministers,

who gave direct access to the Service Chiefs and abided by

their advice. The management of national security by CCPA

remained inept due to following fundamental weaknesses:

• This august body had little independent expertise of its

own.

• Its very designation entailed that neither it was intended to deal with national security on an exclusive basis nor it was supposed to monitor the national security scene on a continuous basis.

• Its very designation entailed that neither it was intended to deal with national security on an exclusive basis nor it was supposed to monitor the national security scene on a continuous basis.

• It merely dealt with issues raised by the Ministry of Defence which itself was ill-equipped to encompass the whole gamut of national security issues.

• Service Chiefs were not members of CCPA. They were only occasionally asked to be in attendance.8

The CCPA was later renamed as the Cabinet Committee on

Security (CCS). There were other committees too like the

Joint Planning Committee, Joint Intelligence Committee, Joint

Training Committee, Inter-Service Equipment Policy Committee

etc., which were formed, based on the recommendations of Lord

Ismay and have continued to this day with some modifications.

It may be worth mentioning that the spirit behind the higher

defence organization proposed by Ismay for providing direct

interaction between the political executive and the Defence

Services and minimising bureaucratic control have thoroughly

got subverted.9

Later in the mid 1980s for defence planning, two

organizations - the Defence Coordination and Implementation

Committee and the Defence Planning Staff (DPS) were also

formed. The former meets only on a need-based manner while

the latter wound up within a few years.

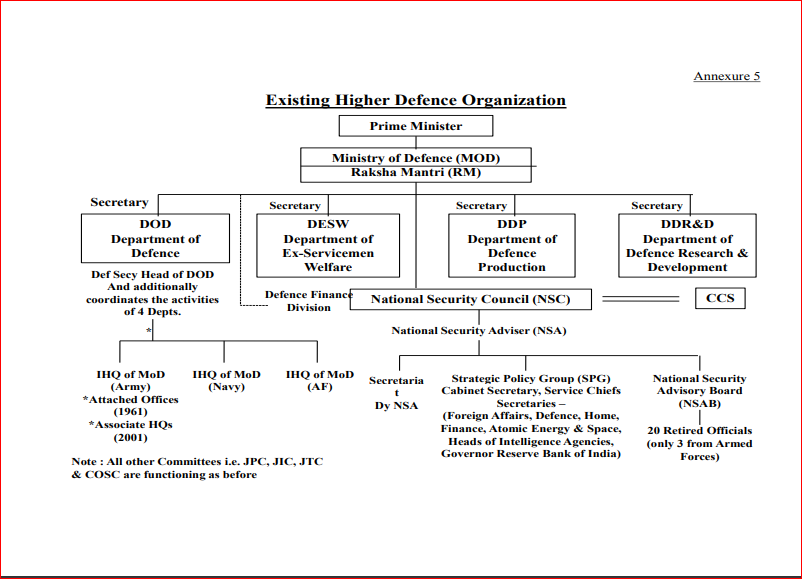

As regards, Ministry of Defence (MoD), it is manned exclusively

by civil officials and is organised as four departments:

departments of defence, defence production, defence

research and development, and Ex-servicemen’s Welfare.

Each department is headed by a secretary. The Defence

Secretary besides heading the Department of Defence, is

additionally responsible for coordinating the activities of the

four departments in the Ministry. In addition, there is a Defence

(Finance) division that deals with all matters having financial

implications and performs an advisory role for the MoD.

Service headquarters is the last component of India’s higher

defence structure. Having been degraded to a lowly status of

“attached offices” in 1961, Service Headquarters are not an

integral part of the Government of India - a unique framework

which no other country has!

The nomenclature was changed to “associate headquarters” in 2001, but it was only a change of phrase, devoid of anything substantial. Once again, nomenclature of the Service headquarters was changed as “Integrated Headquarters of MoD (Army), (Navy) and (Airforce)” - a meaningless exercise of semantics without any empowerment or integration of the three Services.10

National Security Council (NSC) was set up in August 1990 but it never got into its stride and remained dormant for a few years. However, it was revived towards end 1998 with a National Security Advisor (NSA). Since then, there have been five incumbents so far for this appointment - three were retired diplomats and two, including the present one are retired intelligence officers.

The NSA has a Secretariat which is headed by a Deputy NSA. This appointment too has been held either by retired diplomats, bureaucrats or intelligence officers. The highly experienced military officers, who have been groomed in this profession throughout their entire career, have not been considered for any of the above appointments. The Secretariat is also filled with officers of various ranks holding senior, middle level and junior staff appointments, with armed forces represented by a few middle level officers.

The NSC and NSA work parallel to the CCS. The NSC comprises a Strategic Policy Group (SPG), a National Security Advisory Board (NSAB) and a Secretariat. The SPG is responsible for inter-ministerial coordination and comprises the Cabinet Secretary, three Service Chiefs and Secretaries of core ministries of Foreign Affairs, Defence, Home, Finance, Atomic Energy and Space besides the heads of the intelligence agencies and the Governor of the Reserve Bank of India. The NSAB consists mainly of a large body numbering nearly 20 of retired officials, of which only three are from the armed forces.12

Organizational structures of India’s Higher Defence Organization from British Period to its evolution till today are illustrated in Annexures 2 to 5.

An Appraisal of Higher Defence Organizations of Major Powers

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s clarion call for India to assume “a ‘leading role’, rather than [as] just a balancing force, globally”13 in fact signifies his larger vision of envisaging India to become a traditional great power. India will only acquire this status when its economic foundations, its state institutions, and its military capabilities are truly robust.14 The organizational strength of its national security structure should be able to leverage the comprehensive national power of the country. To evaluate the effectiveness of National Security structure including the Higher Defence Organization of India, it is imperative that contemporary organizations of major nations be studied to draw useful lessons

The elements of the United States Higher Defence Organization

are (For Organizational Structure see Annexure 6):-

• National Security Council (NSC): Located in the office of the President, the NSC is under the chairmanship of the President; its statutory members include the Secretaries of State, Defense and the Treasury, the Vice-President, the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs (also known as the National Security Advisor), the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Director of Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and Director National Intelligence (DNI). The Secretary of State has primary responsibility for foreign policy and the Secretary of Defense oversees decision-making in relation to US defence policy; the CJCS acts as military advisor to the Council, while the Director CIA is its intelligence advisor

The nomenclature was changed to “associate headquarters” in 2001, but it was only a change of phrase, devoid of anything substantial. Once again, nomenclature of the Service headquarters was changed as “Integrated Headquarters of MoD (Army), (Navy) and (Airforce)” - a meaningless exercise of semantics without any empowerment or integration of the three Services.10

- National Security Council: A policy advisory committee, which was in a way the counterpart of National Security Council in the United States, Defence and Overseas Policy Committee in UK or Committee of National Defence in France, was set up in 1986 under the Chairmanship of Mr. G. Parthasarthy with four ministers and five civil servants as its members while Service Chiefs were excluded from its membership. Whereas in USA, UK and France, there are only ministers and military officers in such committees and not a single civil servant. Main objective of this committee was to take a view of long term options of foreign policy and national security. However, the Committee proved to be a non-starter because Mr Parthasarthy could not provide a pragmatic solution for Sri Lanka and two of the ministers fellfrom political grace. This Committee was soon wound up.11

National Security Council (NSC) was set up in August 1990 but it never got into its stride and remained dormant for a few years. However, it was revived towards end 1998 with a National Security Advisor (NSA). Since then, there have been five incumbents so far for this appointment - three were retired diplomats and two, including the present one are retired intelligence officers.

The NSA has a Secretariat which is headed by a Deputy NSA. This appointment too has been held either by retired diplomats, bureaucrats or intelligence officers. The highly experienced military officers, who have been groomed in this profession throughout their entire career, have not been considered for any of the above appointments. The Secretariat is also filled with officers of various ranks holding senior, middle level and junior staff appointments, with armed forces represented by a few middle level officers.

The NSC and NSA work parallel to the CCS. The NSC comprises a Strategic Policy Group (SPG), a National Security Advisory Board (NSAB) and a Secretariat. The SPG is responsible for inter-ministerial coordination and comprises the Cabinet Secretary, three Service Chiefs and Secretaries of core ministries of Foreign Affairs, Defence, Home, Finance, Atomic Energy and Space besides the heads of the intelligence agencies and the Governor of the Reserve Bank of India. The NSAB consists mainly of a large body numbering nearly 20 of retired officials, of which only three are from the armed forces.12

Organizational structures of India’s Higher Defence Organization from British Period to its evolution till today are illustrated in Annexures 2 to 5.

An Appraisal of Higher Defence Organizations of Major Powers

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s clarion call for India to assume “a ‘leading role’, rather than [as] just a balancing force, globally”13 in fact signifies his larger vision of envisaging India to become a traditional great power. India will only acquire this status when its economic foundations, its state institutions, and its military capabilities are truly robust.14 The organizational strength of its national security structure should be able to leverage the comprehensive national power of the country. To evaluate the effectiveness of National Security structure including the Higher Defence Organization of India, it is imperative that contemporary organizations of major nations be studied to draw useful lessons

• Higher Defence Organization in the United States.

The President of the United States is according to the Constitution, the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Armed Forces. The Secretary of Defence is the “Principal Assistant to the President in all matters relating to the Department of Defense”, and is vested with statutory authority to lead the Department and all of its component agencies, including military command authority second only to the President. On behalf of the President, the Secretary Defense is responsible for formulating policies related to the Armed Forces.15 The Secretary of Defense exercises control by a ‘Defence Planning Guidance’ (DPG) document that includes national security objectives, policies, priorities of military missions and the resources likely to be made available for the projected period. The DPG is prepared in consultation with the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) and is instrumental in initiating the Department of Defense Planning Programme and Budgeting System. The Contingency Planning Guidance (CPG) is another document, prepared in consultation with the CJCS, based on which contingency plans are drawn up by the military that are then vetted by the NSC, before final approval by the President.

The DPG and CPG, therefore, ensure that overall civil control (not control by civil servants) is maintained in the entire planning process.16

The President of the United States is according to the Constitution, the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Armed Forces. The Secretary of Defence is the “Principal Assistant to the President in all matters relating to the Department of Defense”, and is vested with statutory authority to lead the Department and all of its component agencies, including military command authority second only to the President. On behalf of the President, the Secretary Defense is responsible for formulating policies related to the Armed Forces.15 The Secretary of Defense exercises control by a ‘Defence Planning Guidance’ (DPG) document that includes national security objectives, policies, priorities of military missions and the resources likely to be made available for the projected period. The DPG is prepared in consultation with the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (CJCS) and is instrumental in initiating the Department of Defense Planning Programme and Budgeting System. The Contingency Planning Guidance (CPG) is another document, prepared in consultation with the CJCS, based on which contingency plans are drawn up by the military that are then vetted by the NSC, before final approval by the President.

The DPG and CPG, therefore, ensure that overall civil control (not control by civil servants) is maintained in the entire planning process.16

• National Security Council (NSC): Located in the office of the President, the NSC is under the chairmanship of the President; its statutory members include the Secretaries of State, Defense and the Treasury, the Vice-President, the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs (also known as the National Security Advisor), the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Director of Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and Director National Intelligence (DNI). The Secretary of State has primary responsibility for foreign policy and the Secretary of Defense oversees decision-making in relation to US defence policy; the CJCS acts as military advisor to the Council, while the Director CIA is its intelligence advisor

The National Security Advisor plays two roles in the decision-making process; both as the President’s adviser on national security matters and as the senior government official responsible for managing senior level discussions of national security issues. In these tasks, the Advisor is supported by the NSC staff, comprised of civil servants lent out by other agencies, political appointees, and other personnel.

The NSC is stipulated as a statutory body in US legislation, and is sanctioned by an Act of Congress. Specifically, its role is to manage and coordinate foreign and defence policies, and to reconcile diplomatic and military commitments and requirements. It seeks to ensure that the President has adequate information on which to make his decisions, although it does not have an implementation role.17

• Department of Defence (DoD). The Department of Defense is composed of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), Office of the Inspector General, the Combatant Commands, the Military Departments (Army, Navy, Air Force),the Defense Agencies and Department of Defense Field Activities, the National Guard Bureau and other agencies.

• Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS). It consists of Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff as its head, who is the senior most ranking military officer having served as chief of any service; Vice Chairman, always from a different service; the Military Service Chiefs from the Army, Marine Corps, Navy and Air Force, in addition to the Chief of National Guard Bureau.

• Combatant Commands (Unified/Specified). The United States currently has nine Combatant Commands, organised either on a geographical basis or on a global, functional basis. Troops from the various departments (i.e. Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines) are placed under the operational command of unified/ specified commanders.

. Military Departments. The Military Departments are each headed by their own secretary (i.e. Secretary of the Army, Secretary of the Navy and Secretary of the Air Force). The Secretaries of the Military Departments, in turn, normally exercise authority over their forces by delegation through their respective Service Chiefs.18

Consequent to the Goldwater-Nichols Act (GNA) of 1986, the US Military has adopted a command and control (C2) structure in which the authority flows from the President and Secretary of Defense to the commanders of the regional Unified Combatant Commands, who lead joint forces within their respective theatres. Service Chiefs do not possess operational command authority over US troops but they are tasked solely with “the training, provision of equipment and administration of troops”.19

Higher Defence Organization of the UK

In 1963, the three independent service ministries (Admiralty, War Office and Air Ministry) were merged to form the present Ministry of Defence (MoD) in UK. The UK MoD, headed by the Secretary State for Defence, is a unified and integrated organization which functions both as a Department of Government and as a military headquarters. The Secretary of State for defence is assisted by two advisers, one a civilian and the other a senior military officer (For Organizational Structure see Annexure 8):

Permanent Under Secretary of State (PUS) .The PUS is responsible for policy, finance and administration and as the MoD’s Principal Accounting Officer he is personally responsible to Parliament for the expenditure of all public money voted to the MoD for Defence purposes.

Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS). The CDS acts as the professional head of the Armed Forces and he is the principal military adviser to both the Secretary of State and to the Government.

Defence Committees. In general terms defence is managed through a number of major committees that provide corporate leadership and strategic direction:

¾ Defence Council (DC). The DC is the senior committee which provides the legal basis for conduct and administration of defence and this council is chaired by the Secretary of State for Defence. There are 15 other members in this committee who are also responsible for implementing the defence policy, which the body formulates.

¾ Chiefs of Staff Committee. This committee is chaired by the CDS and is the MoD’s senior committee that allows the CDS to gather information and advice from the single service chiefs of staff on operational matters and the preparation and conduct of military operations.

¾ Single Service Boards. There are three single service boards: Navy Board, Army Board and the Air Force Board all of which are chaired by the Secretary of State for Defence. In general the purpose of the boards is the administration and monitoring of single service performance. Each of these three boards has an executive committee chaired by the single service chief of staff.20

• Higher Defence Organization of the People’s Republic of China

( For Organizational structure see Annexure 7. )

As part of the on-going reforms in the PLA, which began in September 2015, previous seven Military Regions have been replaced by five new “theatre commands”. The theatres are aligned against land and, where applicable, maritime security challenges in their respective geographic areas; for instance

Eastern Theatre Command covers the Taiwan Strait and East China Sea while the Southern Theatre Command covers the South China Sea.

These are integrated commands as they draw units from individual services. The Central Military Commission (CMC) has been reorganised with a New Joint Staff Department (JSD) performing the command & control (C2) functions. The PLA has adopted a distinct operational chain of command from CMC to theatre commands and administrative chain of control from CMC to services, akin to the US C2 structure. Accordingly, the service chiefs have only the responsibility to ‘organize, train and equip’ the troops. However, the PLA still retains its soviet orientation, with Political Commissars and Party Committees playing a role in all key decisions. Therefore, the western analysts describe the new PLA C2 structure as “Goldwater Nichols with Chinese characteristics.”22

Faultlines in India’s Higher Defence Structure

Faultlines in our organizational structure need to be identified and seen in the context of contemporary organizations of other countries so that useful lessons are imbibed while restructuring and strengthening our own system. These faultlines can be traced right back from the evolution of our current organization:

FROM Commander-in-Chief to Chief of Staff:

Transformation without Change of Role. In 1955, when the designation of the then commanders-in-chief of the three services was changed to chiefs of staff, the Army, Navy and Air Force acts were just amended to replace the wording ‘Commander-in-Chief’ wherever it occurred in the Acts by the term ‘Chief of Staff’ of the relevant service. By very definition of the concept of ‘Chief of Staff’, they should have become the chiefs of the Armed Forces Headquarters Staff and thereby the principal professional advisers of the defence minister and the Prime Minister as it is prevalent in other democratic polities like the U.S. and the UK.

On the contrary, with such amendment, the chiefs of staff in India became separate entities outside the government structure, and began functioning as the sole commander of the entire force.23

Dual Responsibility: Detrimental to Long Term National Security Planning.

The Chiefs of Staff have to perform two divergent and diametrically opposite roles in their capacity as the principal advisers to the Defence Minister in national security planning and at the same time functioning as commanders of their respective forces. As commanders, their primary aim is to keep the forces combat ready through operational and logistical planning and ensuring availability of appropriate weapons, equipment and infrastructure for operations likely in the near future.

While as principal professional advisers to the government, they have to strike a balance between near-term and long-term future and concentrate on preparing the nation to face the future challenges. Professionalism in national security policy management and planning is different from that in respect of fighting battles at divisional and corps level. Diplomatic manoeuvring requires different skills, knowledge and background than fighting wars at various level of violence. Similarly assessment of likely threats to our security and interests of technological developments, economic constraints on our potential, adversaries etc., also require professional skills of a high order and these are different from professional skills for fighting wars.24 This resulted in the absence of national security planning in the country till 1964, when for the first time a five-year Defence Plan was formulated. The plan was updated in 1966 and in 1969 once again on an adhoc basis. Subsequently it became the rolling plan to be updated every year. Sound planning cannot result from a mere compilation of forces, facilities and equipment requirements but it has to be done on the basis of strategic objectives and long-term intelligence estimates both of which were conspicuously lacking then.25 Formulation of Long Term Integrated Perspective Plan (LTIPP) under the aegis of Headquarters Integrated Defence Staff, started much later, is a step in the right direction but its implementation and execution is a big question

Lack of Integrated Functioning.

Our Parliamentary democracy and the administrative structures are the derivatives of British legacy but the organization evolved for Ministry of Defence and its functioning is one of its own kind having no parallels in any other democracies of the world. In UK, the Ministry of Defence is a unified and integrated organization, which functions both as a Department of Government and as a military headquarters. It is headed by the Secretary of State for defence who is assisted by two advisers: Permanent Under Secretary of State and CDS, both coequals and experts in their respective fields. Further the organization comprises of civil servants, military officers, scientists and procurement executive, each working in his respective sphere and working collectively, and none having any superior functional status. They take joint decisions, where required.

In India, the system is entirely different. Ministry of Defence is an entirely separate entity from the Service Headquarters and is staffed exclusively by civil servants. In 1961, three services ceased to be a part of the Ministry of Defence and became attached offices.

Further, there is Ministry of Finance (Defence), yet another separate entity. Each of the three entities Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Finance (Defence) and Service Headquarters tend to examine issues in isolation of each other, resulting in triplication of efforts and causing considerable delay.26

The style of functioning of Indian higher defence organization has been criticised by many eminent authorities and committees for the obvious flaws:

• Duplication of efforts between Service Headquarters

and Ministry of Defence, causing waste in terms of

finance, talent and time

. Proposals emanating from senior level at Service

Headquarters being examined by junior officials in

the Ministry lacking the necessary expert knowledge

. Subordination of the military to the civil power should

be in political and not bureaucratic terms.27

• In fact, a Parliamentary Sub Committee in 1978

urged the Government to evolve an integrated set

up amalgamating Service Headquarters, Ministry

of Defence and Financial Adviser so that they may

work in complete cohesion.

But all these observations are of no avail as the all powerful Indian bureaucracy has successfully blocked all attempts towards integration.

• Bureaucratic Dominance and Continued Degradation of Service Chiefs’ Status.

Based on the recommendations of Lord Esher when officer from Indian Civil Service replaced the military officer (a Major General) and assumed the new appointment of Defence Secretary in 1921, he was subordinate of the Commander-in-Chief. At the time of independence, control over Ministry of Defence had passed from the Commander-in-Chief to the Defence Minister. It had happened when the Interim Government came to power in 1946. However, the role of the Ministry was limited and the protocol status of the Defence Secretary (who had been subordinate of the Chief) still ranked junior to all the Principal Staff Officers at Army Headquarters.29

In 1947, a committee of three senior Indian Civil Service (ICS) officers had suggested structuring of the Defence Ministry on the lines of Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) and in the process, had also aimed at lowering the status of the military officers much in the same way as that of the police officers in relation to the ICS. Fortunately, Lord Mountbatten being the Governor General at that time, he ensured that the Service Chiefs retained their higher status over the Defence Secretary.30 In 1948,

after the departure of Lord Mountbatten,

another attempt was made

by setting up Defence Secretary’s Committees for the Army, Navy and Air Force and bringing in Services Chiefs as members under the Chairmanship of Defence Secretary.

Service Chiefs being senior in status to the Defence Secretary, they never attended and these committees remained non-starters.

Ultimately, the civil servants succeeded in establishing their dominance when fifteen years later in 1963, Cabinet Secretary was given higher protocol status than Service Chiefs. Bureaucratic dominance over the higher defence mechanism progressed further- when the DCC was first changed to Emergency Committee of the Cabinet and then to CCPA, attendance of Service Chiefs was not considered necessary at all its meetings. Rather, the Defence Secretary started representing the Defence Services at the crucial meetings. The process of isolating the Defence Services from decision making appeared to have reached its climax when Service Chiefs were excluded from the membership of Policy Advisory Committee formed in 1986 - a precursor to the National Security Council.31 In 1999, when NSC was established, Service Chiefs or Chairman Chief of Staff Committee were not considered important enough to be member of this council but were placed in Strategic Core Group - another means of extending bureaucratic dominance over the national security apparatus. The NSC in the United States and UK have Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff and Chief of the Defence Staff as statutory members respectively with other ministers under the chairmanship of the head of the state. There are no civil servants in this council except for NSA who is assistant to the Head of the State for National Security Affairs and acts as Secretary, providing the secretarial support to the council through his staff.

• Lack of a True Joint Warfighting Capability.

A full spectrum high intensity war covering land, sea, air, space, information and cyber domain is likely to be the future battlefield milieu over the coming decades. To achieve victory in this milieu, integrated theatre operations would be imperative.

Presently a semblance of tri-service integration is being achieved through the Chief of Staff Committee (COSC), a British legacy, having been established in India in the early Thirties. Beside the functional inefficiency, the extant interservice rivalry in the system is highly counter-productive. On the other hand, having been inspired by the U.S. military’s successful joint operations during the first Gulf War, China had closely followed the command & control structure adopted by the U.S. military consequent to the “Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986” and have set up their own command & control structure. In fact in 2013, China’s President Xi Jinping himself noted,

“establishing a CMC and theatre command joint command & control system requires urgency and should not be delayed.”32

In our case, while the current political leadership is giving due importance to the modernization of armed forces and wants the Indian Armed Forces to emerge as a reckonable force but no urgency has been shown for the restructuring of higher defence organization - a prerequisite for achieving “Jointness” and “Integrated Approach” towards war fighting.

• Outmoded Concept of Financial Management.

The financial management system, which is still in vogue, was introduced in 1906 to act as a curb on the authority of the Commander-in-Chief.33

The present arrangement of over centralised financial control is unhealthy and leads to unnecessary delays, not only causing huge loss on account of the escalation factor but severely impacts on the operational readiness of the armed forces. Service Chiefs have no authority or financial powers to carry out even repairs or maintenance of their arsenal. Admiral Joshi, former Chief of Naval Staff wrote “While professional competence, accountability, responsibility is with the service, that is not the case with authority….For example, change of submarine batteries, which are available indigenously or for commencing refits and repairs of ships, aircraft, submarines in Indian yards, the service (Navy) does not have that empowerment.”34 The peculiarity of present system is that the Financial Advisers tend to become Financial Controllers, and instead of becoming an integral part of decision-making they tend to play the role of decision blocking. If the responsibility and accountability rests with the Service Chief then the financial authority or empowerment must also be vested in him. Therefore, the Defence set up needs to have integrated Finance, rather than the present Associate Finance who exercises authority without any responsibility or accountability.

Reforming and Restructuring: Inescapability of Integrated Theatre Commands/Specified Commands and Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS)

India is likely to emerge as the third largest economy by 2028, behind the United States and China.35 To ensure that high rate of economic development continues unimpeded, an atmosphere of peace and stability is required which can only be assured by a sound military capability. The military power should be competent to protect not only the territorial assets against external and internal threats but also the energy routes, sea lanes of communication and economic assets located abroad. Compared to other great powers of the world, India’s Higher Defence Organization is not adequately structured to comprehensively neutralise all types of threats against its national security

We were inordinately late in taking decision in respect of our economy. In 1973, when Deng Xiaoping put China on the path of modernization, its economy was smaller than India’s . India liberalised its economy 13 years afterwards. In three and half decades, China’s economy not only overtook India’s but its GDP is now Five and half times that of India’s36 - a large gap which is very difficult to bridge, if not impossible. Slow growth of economy affects the power potential of a nation indirectly but any laxity in defence preparedness can result in loss of morale of its people and be very humiliating e.g. 1962 debacle against China. China has been closely watching developments in the U.S. military since 1986 but ultimately it was their charismatic leader President Xi Jinping who launched the comprehensive reforms of PLA in September 2015 (a gap of almost 20 years) and the process is scheduled for completion by 2020.37

In case of India, our renowned strategic thinker Shri K Subrahmanyam and soldier-statesman Lt Gen S K Sinha and many others had been recommending creation of Integrated theatre commands and other related reorganisation/reform since late 1980s but their brilliant endeavours have been lost in the maize of various bureaucratic committees ordered from time to time. Any delay in restructuring of our higher defence organization will be detrimental to national security. Acquisition of modern weapons and technology alone from friendly foreign countries in bits and pieces is not good enough unless organization at the apex is capable to provide: longterm integrated future-oriented planning, doctrine for effective employment of forces with their armaments, jointness of three services in planning as well as execution of operations and so on. Akin to People’s Republic of China, India also needs comprehensive reform of its higher defence structure urgently and it can be achieved only through the direct intervention of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who has proven his acumen of taking bold initiatives . The bureaucracy will continue to place hurdles on the path of reform as they have been doing since 1947 and even before. Their behaviour can best be described in the words of renowned sociologist Morris Janowitz,

“The intimate social solidarity of the military profession is both envied and resented by civilians”. 38

Having identified the faultlines in India’s higher defence organization and the impediments which prevent its evolution, the edifice of the organization needs to be restructured and reformed, essentially involving: Creation of Integrated Theatre Commands and Specified Commands; Redefining the chain of command and control; creation of Chief of the Defence Staff or equivalent.

• Integrated Theatre Commands and Specified Commands.

Modern war requires jointness, interoperability and close integration between the three services not only for planning at the national level but also for execution at the theatre level. Necessity of close integration was established during the Second World War itself when Field Marshal Montgomery had moved the supporting Air Force Headquarters from Alexandria and located it adjacent to Eighth Army Headquarters at El Alamein. In Korea, General Walton Walker and General Matthew Ridgeway, commanders of the Eighth Army, met almost daily with General Earle Partridge, who commanded the Fifth Air Force. Similarly in Italy during World War II, the Fifth US Army and the XIIth Air Support Command enjoyed co-located command posts. But these lessons seemed to have been forgotten during Operation ‘Desert Storm’ and it was felt that the command relations between the USAF and the US Army could have been better.39

In India, the command headquarters of services are not co-located e.g. the Army’s Eastern Command is located at Kolkata and its supporting Eastern Air Command is at Shillong. Western and Northern Commands of the Army are at Chandimandir and Udhampur respectively, whereas their supporting Western Air Command is at Delhi. Army’s Southern Command is at Pune while the Air Force South Western Command is at Jodhpur. Same way the Navy’s operational commands and their supporting Air Force commands are geographically segregated. A semblance of coordination is being achieved by co-locating Advanced Headquarters of Air Force Commands alongside Army and Navy Commands, they are supporting. That is not good enough.

To achieve true integration and synergy, we need to create integrated theatre commands which are strategically oriented and unified to meet the emerging threats:

• Integrated Western Theatre Command (Under Army GOC-in-C): facing Pakistan from the plains of Punjab, through Thar Desert of Rajasthan to Rann of Kachchh in Gujarat. Has under its command all Army & Air force formations covering the Area of responsibility (AOR) of existing Western, SouthWestern and Southern Commands.

. Integrated Northern Theatre Command (under Army GOC-in-C): facing Pakistan and China in the mountainous regions of J&K and Ladakh. Has under its command all Army & Air Force formations covering the AOR of existing Northern Command.

• Integrated Eastern Theatre Command (under Army GOC-in-C). facing China in the Northeast. Has under its command all Army & Air Force formations covering the AOR of existing Eastern Command.

• Integrated Southern Theatre Command (under Naval Admiral). Has under command the maritime fleets and air assets deployed for defence of Western, Eastern and Southern seaboards. Andaman and Nicobar Command shall also come under it.

• Integrated Aerospace Command (under Air Force Air Marshal). Responsible for Air defence of the country including Ballistic Missile Defence and strategic air offensive

• Integrated Logistics Command. Responsible for organizing and coordinating movement of men and material from one theatre to another within the country as also to overseas theatre of operations using air, land and sea transportation.

In addition, the emerging threats necessitate raising of THREE SPECIFIED COMMANDS

• Strategic Forces Command (SFC). Already existing for command and control and employment of complete nuclear assets under triad.

• Special Operations Command. On the lines of the US structure to counter the asymmetric threats. It has been proposed by Naresh Chandra Committee in 2011.

• Cyber Command. For defending national interests against attacks that may occur in cyberspace, the so-called ‘Fifth Domain’ of warfare.

Redefining the Chain of Command and Control.

Having realised that Integrated Theatre Commands and specified commands are essential for fighting and winning wars in the future battlefield milieu, the existing command and control setup has to undergo a complete metamorphosis. With the armed forces having moved into areas of longer reach weapons and synergy between the three services required to achieve force multiplier effect in the battlefield, the present concept of chiefs of staff being the overall commander of all forces of his service is no more practicable. There has to be two distinct chains of command and control:

(a) Chiefs of Staff being the heads of their respective services should be responsible for organizing, training and equipping their forces;

( b ) Formulating operational plans and conduct of operations by Integrated Theatre Commands/specified commands should be the responsibility of the Chief of the Defence Staff or equivalent.

• Chief of the Defence Staff or Equivalent. The necessity of a Supreme Commander at the theatre level was realised and got fully established during the Second World War. After the war, this concept was adopted into the Defence organization at the national level, with the United States instituting Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff under the National Security Act of 1947 and the UK establishing Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS) in 1958. Many countries of the world follow this arrangement in one form or the other.

Probably, India is the only country in the world,

where

the Secretary Department of Defence - a generalist civil servant drawn from diverse background and who serves in the Ministry of Defence for a fixed tenure - has been made responsible for

“the Defence of India and every part thereof including preparation for defence”

according to the Government of India AOB/ TOB Rules.40 Does it mean that a bureaucrat heading the MInistry will formulate the operational plans for war fighting and Chiefs of Staff will execute it. If that was an anomaly then it should have been rectified by now. But this neglect is either due to politicians’ detachment and indifference towards matters relating to defense forces or alternatively, it serves the purpose of bureaucrats bossing over the military brass. This situation can best be explained in the words of Late Shri K Subrahmanyam,

“Politicians enjoy power without responsibility, bureaucrats wield power without accountability, and the military assumes responsibility without direction.”41

Shri K Subrahmanyam, who was earlier (in 1987) vehemently opposed to the idea of CDS,42 while heading the Kargil Review Committee agreed to the creation of the post of CDS. Subsequently, Group of MInisters (GoM) led by the then Deputy Prime Minister L K Advani also recommended the same. More than a decade elapsed but the post of CDS remained elusive. In June 2011, another high level committee was ordered under former Cabinet Secretary Naresh Chandra who submitted its detailed report to the Prime Minister in mid-2012.43 It is reported that the Committee has recommended appointment of a Permanent Chairman Chiefs of Staff Committee.

Rather than handling the necessity of CDS in a piecemeal manner as an issue where Armed Forces are shown seeking appointment of an all powerful Four-star General, it is high time that the urgency of a single point Military Adviser responsible for drawing up operational plans of Integrated Theatre and specified commands, akin to the CJCS of the US, be brought to the notice of Political Executives. Name of the post is immaterial - whether it is CDS, Permanent Chairman COSC or any other synonym, but his role and responsibility must be categorically defined:

• He will be the Principal Military Adviser to the Defence Minister and the Prime Minister.

• He will be responsible for formulating operational plans for Integrated Theatre Commands and exercise operational control ‘only’ over all field formations and provides inputs to Defence MInister, Prime Minister and CCS on all operational issues.

He will have no operational command authority neither individually nor collectively as the chain of operational command will go from the Prime Minister to the Defence Minister and from the Defence Minister to the Integrated Theatre Commands/ Specified Commands.

He will advise the Prime Minister and the CCS regarding selection of nuclear targets along with detailed technical, tactical and strategic analysis.

He should be a permanent member of the CCS chaired by the Prime Minister, as also of NSC

• HQ Integrated Defence Staff (IDS) and ‘Directorate General of Operations’ of three services will function under him to enable him to perform his role and responsibilities.

• He will be the Chairman of the COSC (JCS), with individual Service Chiefs having a right of direct access to the Defence MInister and the Prime Minister. Present format of the COSC may have to be changed because of its obvious disadvantages.

The very basis and the functioning of COSC has some serious flaws: First, the longest serving Chief of Staff in office becomes the Chairman of the Committee, ensuring rotation of Chairmanship amongst the three Services. Since, the Chairman continues to head his own Service, loyalties do get divided at critical junctures; Second, with a maximum permissible tenure of three years for a Service Chief, the better portion is passed before one becomes “the longest Serving Chief” to head the COSC. Thus, usually a Chairman gets a tenure of about one year or so and that is too short a period to achieve meaningful formulation, initiation and direction of any long-term policy; Third, the most importantly, the Committee is not supported by any permanent joint staff to sustain such endeavours; Fourth, the Chairman has not been bestowed with any elevated status therefore the quality of coordination is greatly dependent upon the personality equation; Fifth, with a view to ensure a functional harmony within the Committee, hard decisions are possibly avoided and compromises arrived at; Lastly, COSC continues to remain an entity outside the Government.44

With the role and responsibility envisaged for the CDS, COSC in the form in which it is functioning is not a worthwhile organisation to continue with. Ideally, it should be a Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) as part of the CDS Secretariat, properly equipped and staffed from where he can coordinate, integrate and synergise efforts with three Service Chiefs. If this new organisation is acceptable then it may not be sacrosanct to adhere to the nomenclature of CDS or Permanent Chairman COSC. Rather, it will give an opportunity to the present Government to create the appointment of ‘Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff’ as it is being followed in the US and bestow a status upon the senior-most General of the Indian Military so that he can stand as ‘one among equals’.

Fear psychosis created in the minds of political leadership about the attendant risk of a military coup by concentrating too much authority in a man in uniform has no rationale if one studies the responsibilities of the CDS explained as above and his hierarchical position in the chain of command and control.

In fact, it is the bureaucrats’ fear of losing grip over the Services that they give vent to such feelings. Another aspect that introduction of this system, will lead to domination of the Army over other two services is also not valid because Army predominance is common in almost every country and firstly there is little reason to doubt the integrity of such a senior officer toward the greater interest of the nation as a whole and secondly this controversy can be avoided by making this appointment rotational between the three services.

To enable these reforms and organisational restructuring to be effectively implemented and our military power to emerge as a potent war winning force, complete integration of MoD and services headquarters needs to be carried out. Therefore services headquarters should form part of Ministry of Defence and ceased to be ‘attached offices’. Then, the services headquarters should accept foreign service, IAS, intelligence and defence science officers as well as professional economists. Further,

‘Military Wing’ needs to be recreated in the Cabinet Secretariat by locating the CDS office over there.

The Defence Secretary, being the civilian adviser to the Defence Minister, will be responsible for policy, budget, financial control, accounting and administration in the Ministry of Defence.45 There shall not be requirement of a separate Financial Adviser (Defence), thereby avoiding duplication or rather triplication of efforts within the Ministry of Defence. Once the CDS becomes a Permanent Member of the NSC, he will be able to provide considered advice based on detailed analysis carried out by his staff. Hence the requirement of SPG and NSAB may become superfluous and can be dispensed with.

• Options Available.

Likely options available to achieve reform and restructuring of India’s Higher Defence Organisation are:-

Option 1. Based purely on merit-cum-experience, select and appoint CDS/CJCS forthwith from any of the three Services. He should be entrusted with the responsibility to set up his own headquarters, establish Chain of Command and Control and formalise setting up of Integrated Theatre Commands and create specified Commands within a timeframe of two-three years

Option 2. Create Integrated Theatre Commands forthwith by co-locating assets of Army/Navy/AF at the designated headquarters location based on availability of infrastructure and appoint their GOsCin-Cs from respective service, based on role/tasks of the Command. Allow these commands minimum two-three years to integrate and synergise their war fighting doctrines through training/discussions and live exercises. In the meantime, select and appoint CDS/CJCS based on merit-cum-experience who will setup his own headquarters and establish functioning parameters with both up and down the Chain of Command.

Option 3. Comprehensive reform and restructuring of India’s Higher Defence Organisation should be accepted and approved by the Cabinet with timelines drawn for establishment of Integrated Theatre Commands, Specified Commands, appointment of CDS/CJCS and chain of operational command and operational control. Since, it is a prestigious enhancement of India’s Comprehensive National Power and the world powers should take note of it, the Prime Minister should launch the ‘Reform and Restructuring’ in a grandiose manner, giving a strict timeframe for its completion.

The Bureaucrats will always come out with a different option to delay and probably obviate the complete process so that their own power is not diluted. But if the nation has to emerge as a great power, then the Prime Minister should take the initiative by adopting Option 3.

The proposed restructured

‘Higher Defence Organization’

of

India is shown in Annexure 9.

Conclusion

India’s Higher Defence Organization needs to undergo a major transformation to meet the threats and challenges of the emerging global security environment. To achieve a great power status among the comity of nations, the growing economic power must be supported by a matching military capability because comprehensiveness is the key to power. For example, in 1985, the Soviet Union’s GDP was only $741.9 billion compared to Japan’s $1,220 billion. But while Japan was an economic lion, it was a military mouse. The impoverished Soviet Union, on the other hand, had a military machine on par with the USA’s. Hence, the comprehensive power of the Soviet Union was of the superpower-level, while Japan was merely a major power.46

The US military commenced its transformation in the late 1980s consequent to Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986 and over three decades its reorganised structure has matured through training and real war fighting. In case of China, it had been keenly observing the successful conduct of operations by the US military and the underlying basis for their success but ultimately it was the bold initiative of its paramount leader Xi Jinping, who launched comprehensive reforms and restructuring

of PLA in November 2015 to be completed by 2020.

In case of India, the greatest damage to its ‘Higher Defence Organization’ was done in 1961 when its military was moved out from the MoD and the Services Headquarters were made ‘attached offices’.

This resulted in the political leadership receiving second-hand advice through bureaucrats and the consequences were the disastrous military defeat of 1962.

In 1971, when there was direct interaction between the Prime Minister Late Mrs Indira Gandhi and General (later FM) Sam Manekshaw and operations were launched in conformity with the advice of the latter, Indian Armed Forces wrote a glorious chapter of its unprecedented victory over Pakistan.

Rather than evolution for betterment, the organizational damage remained buried and over these 55 years the role and importance of military hierarchy further got diluted by the bureaucratic onslaught. The role of military is not confined to only carrying out directives but it must render advice and closely interact with the decision makers so that realistic directives can be formulated. Therefore the interaction between the military hierarchy and political executives must be direct and intimate but due to lack of acumen and inclination with the political leadership, their role has been usurped by the civilian bureaucracy.

The situation can be retrieved and organizational strength of India’s Higher Defence can be restored only by a leader like Prime Minister Narendra Modi who has the strength of his own conviction and has the ability to take bold initiatives. He had said, “his foreign policy does not believe in cowering to or staring at other nations’ but looking into their eyes with confidence”.47

The confidence of a nation must be supported by its ‘comprehensive national power’ of which the military power is the most important ingredient. To place our priorities in correct perspective, it is high time that the fighting potential of India’s armed forces must be enhanced by organising it into ‘Integrated Theatre Commands and specified commands’ and develop a joint command and control system as it is functioning in the US and also being followed by China. It must be remembered that as an economic power, a nation can compete with others by acquiring first, second, third positions and so on but

‘In war there are no runners up’.

NOTES

1. Walter Gorlitz, “The German General Staff, Its History and Structure 1657 - 1945”, Hollis & Carter Limited, London 1953, p. 63.

2. Jasjit Singh, “Indian Security : A Framework for National Strategy”, Strategic Analysis, Vol XI, No. 8, November 1987, p. 885.

3. Brigadier (Dr.) Rajeev Bhutani, “RISE OF CHINA: 2030 and Its Strategic Implications”, Pentagon Press, New Delhi, 2016, pp 32-33.

4. K. Subrahmanyam, “Higher Direction of Defence and Its Organisation”, Strategic Analysis, Vol. XI, No. 6, September 1987, p. 646.

5. Lt. Gen. S. K. Sinha, PVSM (Retd.), “Higher Defence Organisation (Part I),” U.S.I. Journal, January - March 1991, p.

6; and Nagendra Singh, “The Theory of Force and Organisation of Defence in Indian Constitutional History From Earliest Times to 1947”, Asia Publishing House, New York 1969, p.235. 6. Ibid, pp 7 - 10.

7. Maj. Gen. Rajiv Narayanan, “Higher Defence Organisation for India : Towards an Integrated Approach”, Indian Strategic Studies, 12 Aug 2016 available at strategicstudyindia.blogspot.in/2016/08/ higher-defence-organisation-for-india.html

8. P. M. Pasricha, “India’s Defence Policies”, Strategic Analysis, Vol. IX, No. 7. October 1985, p.705.

9. Lt. Gen. S. K. Sinha, PVSM (Retd.), op.cit. pp 11-12.

10. Lt. Gen. Vijay Oberoi, “Need for Structural Changes in India’s Higher Defence Management”, Indian Defence Review, Issue Vol. 30.1, Jan - Mar 2015, available at www.indiandefencereview.com/spotlights/ need-for-structural-changes-in-indias-higher-defencemanagement/

11. Lt. Gen. S. K. Sinha, PVSM (Retd.), op.cit. pp. 13 - 14. ( Mr Arun Nehru, the then Minister of Internal Security and Mr Arun Singh, the then Minister of State for Defence, both of them fell from political grace.)

12. Lt. Gen. Vijay Oberoi, op.cit.

13. Indian Press Information Bureau, Prime Minister’s Office “PM to Heads of Indian Missions”, press release, February 7, 2015, available at http://pib.nic.in/newsite/ PrintRelease.aspx?relid=115241.

14. Ashley J. Tellis, “India as a Leading Power”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 04, 2016 available at carnegieendowment.org/2016/04/04/indiaas-leading-power-pub-63185

15. “Organizational Structure of the United States Department of Defence” available at en.wikipedia.org.

16. Air Marshal Dhiraj Kukreja, “Integration of Service Headquarters with Ministry of Defence”, Indian Strategic Studies, Issue Vol 27.3 Jul-Sep 2012, 11 November 2012, available at strategicstudyindia.blogspot. in/2012/11/integration-of-service-headquarters.html

17. Susanna Bearne, Olga Oliker, Kevin A. O’Brien, Andrew Rathmell, “National Security Decision Making Structures and Security Sector Reform”, RAND Europe, 2005, pp. 16 - 19

18. United States Department of Defence available at https:// en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Department_ of_Defense.

19. Brigadier (Dr.) Rajeev Kumar Bhutani (Retd.), “Transformation of Chinese People’s Liberation Army : Reforms, Restructuring & Modernization”, Centre for Joint Warfare Studies (CENJOWS) New Delhi, 2016, p.24.

20. “The Management of Defence in the UK” available at www.armedforces.co.uk/mod/listings/l0004.html

21. Gen. (Retd.) Ehsan ul Haq, “Restructuring Higher Defence Organisation of Pakistan” Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILdAT), August 2013, p. 13. available at www.pildat.org/Publications/publication/CMR/ RestructuringHigherOrganisationofPakistan_ DiscussionPaper.pdf

22. Brigadier (Dr.) Rajeev Kumar Bhutani (Retd.), op. cit, pp. 21 - 24.

23. K. Subrahmanyam, op.cit., pp. 647 - 648.

24. Ibid, pp. 648 - 650.

25. P. M. Pasricha, op.cit., p. 698.

26. Lt. Gen. S. K. Sinha, PVSM (Retd.), “Higher Defence Organisation, (Part II)”, U.S.I. Journal, April - June 1991, p. 143.

27. Ibid. p. 143. (The Administrative Reforms Commission of 1967 had two committees dealing with Defence matters : Nawab Ali Yawar Jang Committee and Mishra Committee)

28. Ibid., pp.143 - 144.

29. Lt. Gen. S. K. Sinha, PVSM (Retd.), op.cit. (Part I), pp. 9 - 10.

30. V. K. Shrivastava, “Higher Defence Management of India : A Case for the Chief of Defence Staff”, available at www.idsa-india.org/an-sept1-00.html; and Lt. Gen. S. K. Sinha, PVSM (Retd.), op.cit. (Part I), p.10. [The committee consisted of Mr. R.N. Banerjee, the then Home Secretary, Mr. Vishnu Sahay, Secretary Kashmir Affairs and Mr. H. M. Patel, Defence Secretary]

31. Lt. Gen. S. K. Sinha, PVSM (Retd.), op.cit. (Part I), pp. 12 - 14.

32. Phillip C. Saunders and Joel Wuthnow, “China’s Goldwater - Nichols? Assessing PLA Organizational Reforms”, National Defense University, April 2016, p.7., available at http://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/ Documents/stratforum/SF-294.pdf

33. Lt. Gen. S. K. Sinha, PVSM (Retd.), op.cit. (Part II), pp. 148-149.

34. C. Uday Bhaskar, “Reforming India’s Higher Defence Management : Will Modi Bite the Bullet?”, Indian Defense News, 16 October 2014, available at file:/// storage/emulated/0/Download/reforming-indias-higherdefence.html

35. “India to be world’s 3rd - largest economy by 2028, UK think tank says”, The Times of India, 28 December 2013, available at timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/indiabusiness/India-to-be-worlds-3rd-largest-economy-by2028-UK-thinktank-says/articleshow/28059381.cms

36. Brigadier (Dr.) Rajeev Bhutani, “RISE OF CHINA: 2030 and Its Strategic Implications”, op.cit., p.128.

37. Brigadier (Dr.) Rajeev Bhutani (Retd.), CENJOWS, op.cit., p.1.

38. Nitin A. Gokhale, “Higher Defence Management in India : Need for Urgent Reappraisal”, CLAWS Journal, Summer 2013, p.26.

39. P Mason Carpenter, “Joint Operations in the Gulf War : An Allison Analysis”, June 1994 available at https://fas. org/man/eprint/carpente.htm

40. Admiral Arun Prakash (Retd), “Defence Reforms : Contemporary Debates and Issues”, p.24, in Air Marshal B D Jayal, General V P Malik, Dr Anit Mukherjee and Admiral Arun Prakash, “A Call for Change: Higher Defence Management in India”, IDSA Monograph Series No. 6, July 2012, Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses.

41. C. Uday Bhaskar, op.cit.

42. K. Subrahmanyam, op.cit.,p.657.

43. Dr Anit Mukherjee, “Introduction : A Call for Change”, p.9. in IDSA Monograph Series No. 6, July 2012, op.cit.

44. P. R. Chari, “Reforming the Ministry of Defence”, Indian Defence Review, January 1991, p. 47; and V. K. Shrivastava, op. cit.

45. K. Subrahmanyam, op.cit.,p.654.

46. Brigadier (Dr.) Rajeev Bhutani, “RISE OF CHINA: 2030 and Its Strategic Implications”, op.cit., p.33.

47. “We won’t look down, nor stare but look into eyes : PM Modi”, Business Standard, 24 November 2015, available at www.business-standard.com/article/newsani/we-won-t-look-down-nor-stare-but-look-into-eyespm-modi-115112401111_1.html